From Japan to Thailand, and on to the ASEAN community

Sucharit Koontanakulvong

President of the Technology Promotion Association (Thailand-Japan)

2013 Presentation Ceremony for the Japan Foundation Awards

The Japan Foundation Awards (2013) Commemorative Lecture

The Technology Promotion Association (Thailand-Japan), or TPA, was founded in 1973 and it celebrated its 40th anniversary in January 2013. On hearing that TPA had become a recipient of the Japan Foundation Award, we reflected on why we have been honored with this great prize and analyzed our activities over the years. With these thoughts in mind, I would like to talk to you today about our organization, TPA.

Circumstances surrounding the founding of the Technology Promotion Association (Thailand-Japan) (TPA)

Let me begin by talking about the situation in 1973 when the Technology Promotion Association (Thailand-Japan) was founded. At that time, Thailand was in the process of changing from a military dictatorship [to a democracy]. Anti-government protests by citizens and students were on the rise, and the time was ripe for anti-Japan sentiments caused by the export deficit with Japan. The Japanese government was searching for ways to cope with the situation, considering various types of grant aid and yen loans, but it was also visualizing a new type of co-operation system. For the Thai government too, overtly pro-Japan policies would generate public disapproval, so the choices were extremely delicate.

The Japanese side considered asking Mr. Goichi Hozumi, the first head of the Asian Students Cultural Association (ABK) and the Association for Overseas Technical Scholarship (AOTS), to take charge of building up a new structure on a private-sector basis rather than as an official government initiative. With its attempt, it was expected to explore the possibility of bringing together people who had studied or been trained in Japan and with them establishing a new structure from a neutral standpoint. But among these alumni, there must have been some who had so much reflection about the true implications of concepts such as "pro-Thailand, pro-Japan" and "neutral." Emerging from these debates, the Technology Promotion Association (Thailand-Japan) came into being as an organization to take a neutral position while supporting various ventures. In Japan, the Japan-Thailand Economic Cooperation Society (JTECS) was founded as a direct counterpart.

On the Japanese side, Mr. Goichi Hozumi played a key role in founding JTECS. On the Thai side, it was believed that an organization would not function sufficiently well, only with a gathering of alumni, trainees and researchers, and so there was a need to find a leader who was well respected in Thai society. The founding members of TPA invited Mr. Sommai Huntrakul, who was a former Finance Minister and had studied in Japan, to take the helm. According to my older colleagues, when they visited Mr. Sommai to ask him to be their leader, he asked them, "Will this organization really take a neutral stand?". Mr. Sommai did not give them a "Yes" immediately when they approached him, but at first gave the matter deep thought as a former Finance Minister and asked many questions about the organization's principles and structure.

The Principles of TPA

These are the principles created by the founding members:

The First Principle: The activities of this organization must be of real benefit to Thai society, and in order to be self-reliant, we shall not include Japanese members on the board of directors. The organization will be run by Thai board members. This will be a proof of our autonomy.

The Second Principle: We shall need a venue to carry out our activities. This means building our own center. In order for this to become a reality, we shall be financing it with some Japanese subsidies.

The Third Principle: The founding members should not be satisfied with forming an ordinary association. Our purpose, after all, was to set up a school that could provide technical education. This was the 1970s, so there was a need to promote superior Japanese technology and to train personnel who could cope with that technology. In that way, we would contribute to the development of industries in both Japan and Thailand in the long term.

The Fourth Principle: Communications between Japan and TPA would be carried out exclusively through JTECS.

And the Fifth Principle: In order to run TPA as an independent and long-lasting organization, the Thai side, as a rule, should have responsibility for overseeing the subsidies from Japan and for managing its own finances.

Only after a close study and understanding of these principles did former Finance Minister Sommai agree to head the association.

At the outset, of the five original principles, we were not able to achieve the third one which was to set up the school. This was because we could not gain the Education Ministry's permission to open the school since it would be seen being too pro-Japanese. The association was able to run short training courses but setting up a school, as such, would have been difficult under the government of the day. So in the end, TPA was founded on the basis of the other four principles. The association has been run along those lines to this day, and I believe this has been a key to TPA's growth.

May 24, 1973 marked the beginning of TPA, and Mr. Sommai and Mr. Hozumi gave keynote addresses at the opening ceremony. Of course at the beginning we did not have our own building and so rented an office in the U-Chu Liang building on the other side of Lumpini Park and began our activities.

In those first days, our first concern was not to carry out seminars on Japanese technology but to start a Japanese-language school. We thought people would not be able to obtain the new skills without knowledge of Japanese language and culture.

But that was not to say it was an ordinary Japanese-language school. We focused on three aspects: the Japanese language, Japanese culture and technical training. There were plenty of private schools teaching Japanese language alone. There were also numerous seminar-type training courses being taught by JICA technical experts and others. In TPA's case, we combined these features and provided a facility where technologists could study the language and the culture at the same time. I believe this is a unique characteristic of the beginnings of TPA.

In those days, the Japanese listening materials were recorded on cassette tapes, and PowerPoint did not exist yet, so the teachers had to write everything on blackboards. We arranged to dispatch Japanese-language experts to give short seminars at the school for two to three days each time, and also carried out the technical training with the assistance of interpreters. We conducted experiments and technical training which included simple calibration and practice sessions.

Goichi Hozumi and Sommai Huntrakul at the opening ceremony of TPA on May 24, 1973

TPA's activities--the current situation and achievements

Our activities can be divided into four big phases.

The first phase involved technology transfer. We organized seminars where experts dispatched from Japan gave technical guidance with the help of interpreters. We then set out to publish Thai-language textbooks based on what was taught in those seminars. This is what we did in the first 10 years.

The second phase consisted of developing Thai human resources to become experts, consultants and trainers. We built up a system whereby not only Japanese but Thai experts could be assigned to give trainings in Japanese technology. This phase also took another 10 years.

The third phase involved personnel training of diagnosis and enterprise consultancy services. In 1997, there was a financial crisis which later became known as the Tom Yam Kung Crisis. Around this time, with support from Japan, we had trained about 200 Thai personnel to carry out diagnosis and enterprise consultancy services (shindan-shi). This undertaking had a huge impact on small and medium-sized businesses in Thailand.

In the fourth phase, we could finally turn our attention to education. At the time of TPA's founding in 1973, we were not able to set up a college but in 2007, we opened a university. We made headway into the education business. We established integrative courses and an educational system where students can learn not only technical skills but also the Japanese language and culture. With these courses and system, graduates become ready to work at various businesses.

TPA achieved these goals in 40 years, having allotted 10 years each to developing each phase, and during the growing process, it has made deep impacts on the Thai industrial world.

First phase: The entry of Japanese industries into the Thai market correlated with Thailand's invitation of Japanese companies

In 1973, when the first phase began, Japan was going through an oil crisis, which prompted many small and medium-sized Japanese enterprises to move to Thailand. The enterprises needed Thai personnel, but these people would first have to learn the Japanese language and working culture before they could be actually employed as technicians in Japanese-run factories.

TPA's first 10 years can also be regarded as one of the strategies to support increases in Japanese investment. Japanese industries made inroads into Thailand from 1973 to the early 1980s and TPA played a role in nurturing personnel for Japanese companies.

At the same time, the oil shock had caused a hollowing out of industries within Japan, and those that remained in Japan were forced to begin developing energy-saving technology. By the 1980s, both the major and smaller Japanese manufacturers, which had moved to Thailand, had already started introducing the new technology developed in Japan to their factories there. Green technologies became common place in Thai factories, which were beginning to boast the latest technologies. This was the most beneficial outcomes for the Thai industries.

Second phase: Nurturing Thai technical trainers

By the time of the second phase, Thai industries were not only manufacturing products but were now also turning their attention to more quality process and products via quality control (QC). In this area too, TPA conducted personnel training, developed text books, and spread the know-how of the Japanese style and system of quality control, and thus made a very important contributions to Thai manufacturing industries.

As well as passing on the QC skills, TPA was also engaged in promoting the system by sponsoring the first QC contest in Thailand. Factories in Japan often designate so called "Quality Month" to highlight quality control, and TPA now introduced this idea to factories in Thailand and had factory workers and managers take place in these events. By creating opportunities for employees to work closely towards a common goal, I think TPA also found this to be a most effective way of achieving its aim of promoting technical skills.

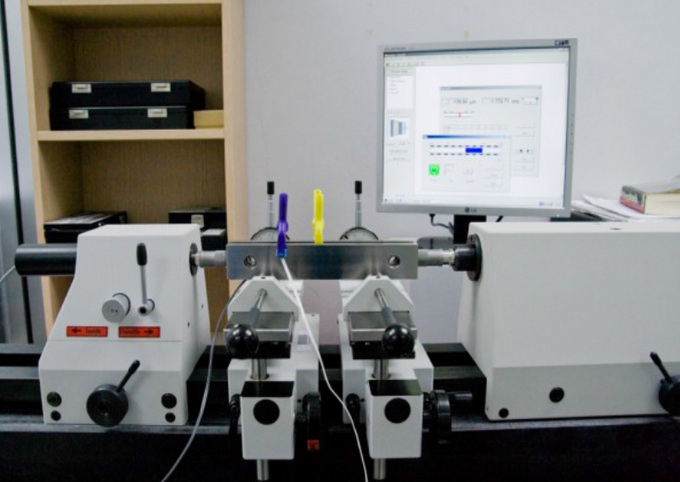

Another service offered by TPA is the calibration of industrial measurement devices. This in itself does not make that much money, but there is a real need for a high level of calibration skills. For example, devices and instruments in some industries need to be accurate to the level of 0.01 millimeter; otherwise they will not be certified. The Thai government is not too keen to carry out such painstaking services. This type of work is ideal for a private-sector business like ours, which can be regarded as a second-party relationship.

From around this period, we tended not to limit our activities to single areas such as developing textbooks, sponsoring competitions, carrying out seminars and training courses, but to undertake a combination of projects. We needed to implement a number of different impressive businesses and contents at the same time if we wanted to be recognized as an authentic organization within Thai society. Otherwise, we would only be seen as an association that was busying itself with activities just for the sake of looking busy. By carrying out a combination of activities, TPA became recognized in every corner of Thai society as a genuine organization. I believe this combination of activities is our hallmark.

A center for industrial instrument calibration

Third Phase: Personnel training for diagnosis and enterprise consultancy business

By the time we had reached the third phase in 1997, Asia was plunged into a currency crisis, and industries in Thailand were badly affected. From an exchange rate of 25-26 baht to the U.S. dollar, it fell to 52 baht to the dollar in six months, and many companies were operating in the red and threatened with bankruptcy. TPA had just built its new facilities and was burdened with a huge mortgage when this crisis hit. It was a highly distressing time for us.

Around this time, TPA introduced a diagnosis and enterprise consulting sector for Thai businesses to adopt selective management processes, and had trained 200 diagnosis and enterprise consultancy experts (shindan-shi) for this purpose under the Japanese assistances. It took from six months to a year to train people to become experts, and Thailand was probably the only country outside Japan to have begun this endeavor. This business had huge impacts on both TPA itself and on industries in Thailand. By taking on this challenge and achieving a successful outcome, TPA was able to build up a system that could take on even bigger and integrated projects.

The financial crisis of 1997 was both a crisis and a window of opportunity. This combination of crisis and opportunity was particularly valuable for TPA, and within the relatively short period of two to three years, Thai industries had gained enough strength to recover. In that sense, the Japanese government's Miyazawa initiative was a most effective [in aiding the recovery].

From then onwards, instead of just focusing on urban areas, we extended our activities to the regions, setting up a Japanese-language school in Rangsit in the suburbs of Bangkok, and we also built a new facility in Pattanakarn, in Bangkok.

We began by offering training in individual areas of study, but then we moved on to offer a combination of personnel-training needs which we call "total human package." For example, we will provide a combination of language and cultural training for manufacturing personnel, and the client company will be able to receive services pertaining to the running of the whole factory. This makes use of our system of providing experts in diagnosis and enterprise consultancy and we believe this is a training pattern unique to TPA.

A new Pattanakarn center founded in 1998

Diagnosis and enterprise consultancy services

Fourth Phase: Entering into education market

By 2007, TPA's cash flow had become healthy and the Thai manufacturing sector was entering an era of new investments, and a shortage of human resources was anticipated. Predicting a recovery and expecting a shortage of engineers, we considered setting up a university: the founding of the Thai-Nichi Institute of Technology (TNI).

There is an anecdote about how the institute clinched its name. Initially, we went to the Education Ministry to register the name of "Thai-Japan Institute," but were turned down. We were told, "You can't use that name for a private university. You can only use words like Thailand and Japan for names of international organizations or branches of the national government."

We faced a big problem so we went to the Japanese Ambassador of the day to ask his advice. We told him that we were a private association, but we had spent the last 30 to 40 years building up a strong relationship between the two countries. The Ambassador agreed to look into the matter and he consulted with the Japanese government to see if there was a way we could use that name.

This was a delicate situation because if the names of our two countries were used for the title of the institute, it would mean that it could not be shut down in the future for any reason whatsoever. If the institute were to be closed down, that would represent a minus image for the bilateral relationship. The Ambassador was confronted with a huge dilemma and it took one month to receive a written consent from Japan. As soon as the letter arrived, we took it to the Thai Education Ministry and showed them that the Japanese government had agreed to the naming. At long last, we were able to register the name we had chosen: Thai-Nichi Institute of Technology.

The opening ceremony was attended by H.R.H. Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn. I believe that Her Majesty also would like the university to become a symbol of the friendship and co-operation between Japan and Thailand.

As I have explained, TPA has been active for 40 years, spending roughly 10 years each on the four phases of its development. Today, our training courses are attended by nearly 2,000 participants a year. And we have double the number of courses taking place on site at factories, attended annually by around 70,000 people. Over the 40 years, we have trained a total of one million people. The main area of training is the Japanese language, but recently we have added English, Chinese and Korean to the line-up, and we plan to add Bahasa Malaysia in the future. We sponsor events such as culture festivals, speech contests and kanji champion matches, and organize an annual joint program with the collaboration of the Japan Foundation, Bangkok. We also run Thai-language courses for Japanese businessmen in Thailand and their families. Altogether, we offer a total of 1,500 courses for a year.

Thai-Nichi Institute of Technology (TNI)

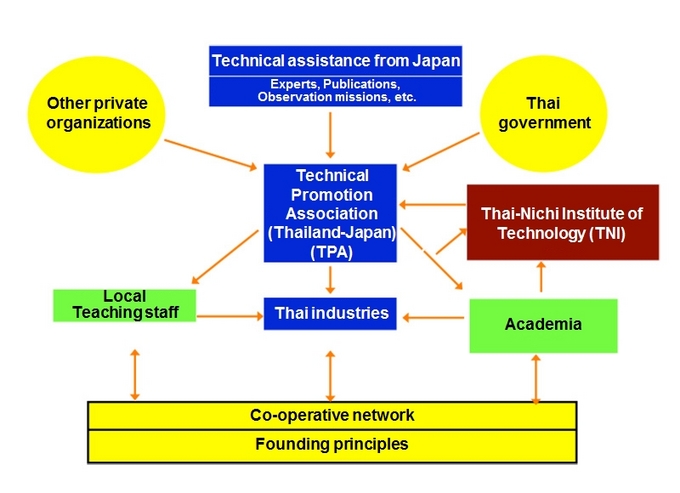

TPA model

TPA is planning to expand its activities to the regions. Both the Thai and Japanese governments are eager to take the manufacturing industries to expand to other areas of Thailand, rather than having them concentrated in Bangkok. In order for that to happen, human resource development must take place in the regions. A number of plans are in the pipeline.

Currently, our courses are attended by an annual total of 15,000 Thai participants. In the 40 years to date, over 200,000 people have learned Japanese, and about 20,000 Japanese have studied the Thai language. We hold Japanese-language contests and train Thai personnel to teach Japanese. This year, we introduced a course to train secretaries for Japanese managers, and we are also training interpreters who will be relatively fluent in technical terminology. This is in response to requests from Japanese companies. Every year, we hold an Open House event and introduce the Japanese language and culture to Thai middle school and high school students. In the course of one week, we welcome 3,000 students who show an interest in Japan.

As for publications, we bring out around 50 books every year and reprint around 200 books. We are also planning to make electronic books that will be available on iPad and other digital media.

Approximately 1,000 students newly enroll the Thai-Nichi Institute of Technology every year, and this year we will see 900 students graduated. The undergraduate school consists of three faculties: engineering, information technology and business administration. Every year, about half the graduates find jobs in Japan-related companies. And about 200 students of the graduate school also find jobs in various sectors.

We strongly believe in the importance of sponsoring contests in order to promote technical skills in Asia. To date we have held contests in the areas of QC, 5S, Kaizen, and the Kano Quality Award. Former Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva honored one of the Kaizen contests with his presence. We are even considering inviting contestants from Laos or taking the 5S contest to Laos. And to encourage young people, we hold robot contests for students in four categories: middle school, high school, technical school and university.

We have also been implementing various training programs, dispatching experts and developing textbooks in the experimental stage, and later on transfer missions/activities to public-sector organizations. For example, Thailand's QC Promotion Association and Energy Conservation Institute started from the experimental groundwork at TPA facilities.

TPA's success story

How has TPA managed to build up such a successful record?

The first reason lies in the basic principles of its founders. They established five principles right from the beginning, stood by those principles and carried on with their activities. The Hozumi spirit is one of the important elements of our success.

The second reason is that all the members of the board of directors serve on a voluntary basis. What's more, the employees are very capable people. It is very important that Thai society recognize the significance of the association. And the way they made the society recognize the significance is also worth noting. As I have said so far, TPA has always moved with the times and looked for new ways to offer the knowledge and skills. I think this has been a very effective approach. Japanese ministries have tended to believe that by assigning experts to disseminate the technology, that knowledge will serve its purpose forever. But in fact, the technology becomes old in the course of five years. Thinking in a 10-year span is too long a period: everything depends on how well we can set up a system of training local experts and introducing new technology every five years to function successfully. That is why I hope TPA will be a flexible organization that throws out the old and replaces it with the new every five years. The ability to read the market is one of the reasons for our existence.

Ever since our start, we have had the five principles to guide us and a network of instructors on the ground. In the area of language training, we currently have 40 teachers who are Japanese nationals and 40 Thai teachers. And in the various technical areas, we have a network of 1,000 experts. I believe this strong foundation is one of the secrets of our success. And a good combination with the Thai government, the private sector and local branches of Japanese companies is what can be called the "TPA model."

Throughout the years we have forged links with a variety of organizations in our neighboring countries. The wide network that includes, of course, JTECS, and ABK, HIDA (the Overseas Human Resources and Industry Development Association), JETRO, the Japan Foundation, and the Thai Industry Ministry, Science and Technology Ministry, and various small and medium-sized Thai companies and banks, all contribute to TPA's strength.

TPA's future

To look at the future of TPA, as I have just stated, it is vital to set clear targets beforehand and to introduce the appropriate technology with consideration on innovations in the Thai technology industry, industrialization in the regions, and business expansion into neighboring countries.

Also important are to nurture experts who will become the core within Thailand and to form networks. Working on a combination of TPA's own management and the development of strategies with the board of directors, I would also like to consider a new TPA network structure.

We may not be able to make use of all that we have experienced so far, but I believe our stance of centering our activities around the teaching of the Japanese language and culture, and Japanese technology continues to be very important. But we shall need to be selective as to the contents.

Prospects for contributions to the ASEAN countries

To a certain extent, the Thai market has matured, and investments by Thai industries into the other ASEAN countries are likely to grow. At the moment there are two mechanisms: ASEAN+3 and ASEAN+6. ASEAN should integrate and adopt the ASEAN way, acting together when it is possible and choosing individual actions when it is not. Geographically, Thailand is situated at the center, within an hour's flying distance from both Laos and Myanmar, so it can act as a hub for nurturing new industries within the region.

From Japan's point of view, ASEAN is no longer just an investment target, but a safe region. ASEAN is now a huge market, rivaling both the United States and Europe, and maintaining that balance should be a diplomacy concern for Japan.

Japan and Thailand should also maintain a balance while helping each other, and they should be aiming for developments that will benefit both countries. In some cases, each can go their own way, while the keywords should be collaboration and friendship at other circumstances. I hope Thailand and Japan will continue to maintain this good combination.

TPA has taken the role of supporting the understanding of the Japanese language and culture. Now I think this can be extended to our neighboring countries. By making use of the experiences of supporting technology transfers and nurturing human resources, we can disseminate this model to our neighboring countries. In fact, we have been already started acting as special advisors on support strategies to the Japanese ministries in Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam.

Living in a continental country, surrounded by many others, we understand our differences in social environment, economies, and cultures. Japan should respect those differences when building up cooperative relationships. Those countries are at different levels of technological development, so again there needs a selective introduction of skills and the building of a support system.

Individual countries have their pride, so there may be objections to coming to Thailand to acquire knowledge of Japanese technology. So TPA would like to continue our activities, not as a teacher-student relationship, but as a brother and sister relationship, and we would "explain" rather than "teach" these skills to our siblings.

Each country should be thinking about how it shapes its own progress, but we would like them to treat TPA as a school and use us to formulate their plans. And as a follow-up, TPA would be more than happy to assist in building up networks. So let us make the most of the two institutions, TPA and TNI, and instead of limiting ourselves to Thailand and Japan, we should build up a collaborative relationship through the friendship between Japan and the ASEAN community.

Sucharit Koontanakulvong

Sucharit Koontanakulvong

Sucharit Koontanakulvong is President of the Technology Promotion Association (Thailand-Japan), or TPA, and Associate Professor of Chulalongkorn University's Faculty of Engineering. He studied in Japan on an Education Ministry scholarship. After undergraduate studies at Kyoto University's Faculty of Engineering, he attended Kyoto University's Graduate School of Agriculture, completed the doctorate course in 1983 and was awarded a doctorate in Agricultural Engineering (Civil). In 1994, he joined the TPA board members, General Secretariat and became its President in 2013.

Keywords

- Cambodia

- Viet Nam

- Myanmar

- Laos

- Technology Promotion Association (Thailand-Japan)

- TPA

- Asian Students Cultural Association

- ABK

- Association for Overseas Technical Scholarship

- AOTS

- Goichi Hozumi

- Japan-Thailand Economic Cooperation Society

- JTECS

- Sommai Huntrakul

- Tom Yam Kung Crisis

- Oil shock

- Currency crisis

- Rangsit

- Bangkok

- Thai-Nichi Institute of Technology

- TNI

- The Japan Foundation Bangkok

- HIDA

- JETRO

- ASEAN

Back Issues

- 2019.8. 6 Unraveling the Maker…

- 2018.8.30 Japanese Photography…

- 2017.6.19 Speaking of Soseki 1…

- 2017.4.12 Singing the Twilight…

- 2016.11. 1 Poetry? In Postwar J…

- 2016.7.29 The New Generation o…

- 2016.4.14 Pondering "Revitaliz…

- 2016.1.25 The Style of East As…

- 2015.9.30 Anime as (Particular…

- 2015.9. 1 The Return of a Chin…