Japanese and Indian Social Entrepreneurs Exploring a Future-oriented Exchange Program Together

Tetsuo Kato

Entrepreneur/ Managing Director of World in Asia

In February 2013, the Japan Foundation dispatched a group of Japanese social entrepreneurs to the cities of New Delhi, Mathura, and Bangalore to conduct fieldwork and visit local social enterprises in India, as an exchange program for Japanese and Indian social entrepreneurs.

Tetsuo Kato, who served as the program coordinator, gives his account of how the participants engaged in future-oriented dialog through the first-hand interaction.

Furthermore, Rajiv Vasudevan, who has brought innovation to India's traditional ayurvedic medicine, and Arathi Laxman, who has been spreading the social entrepreneur movement all over India, are to visit Japan in July, to further their dialog with Japanese social entrepreneurs engaged in trailblazing initiatives in wide-ranging fields.

"Maybe the model or process design that we have cultivated through the regional planning for Yufuin or the Beppu area of Oita Prefecture could be applied to India?" "Maybe in that framework, we could nurture leadership beyond local or national borders?"

This became the starting point for this Japan-India exchange program.

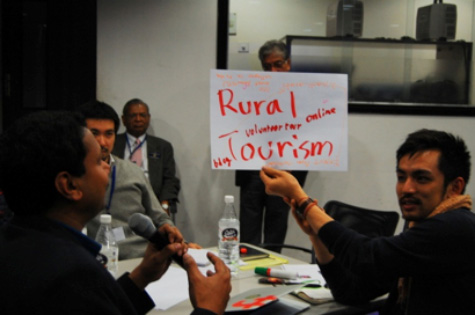

The workshop on the last day of the program was held at the Japan Foundation office, located in India's capital, New Delhi, the urban area of NCT of Delhi. Social entrepreneurs and NGO representatives around Delhi were invited to share the learning process with the Japanese social entrepreneurs. It was a future-oriented session, exploring what we can achieve in the future.

International meetings usually tend to result in the same sort of participants gathering, mostly talking about functionality and interests that can be agreed on in a short time. But this session made us feel that we could perhaps believe in the things born from our interaction.

Thus, we tried to understand each other's social context, and by listening to each other's position, aimed to realize the possibilities of potential partnership.

What we can achieve by comparing Japan and India

The discussion began with someone asking, "What can India learn from the urban and rural structures of Japan? Is there anything we can do to prevent the hollowing out of the villages and rural areas in India?" Then, someone suggested, "Region branding can be achieved through an accumulation of small steps. Why not use pioneering art events or Japanese channels to revitalize rural areas in India?" This led to someone else offering the insight, "The situation that people need inexpensive and safe medical services and education is the same. Maybe we could build a new model in India, where the government is still in the process of implementing regulations." Then, with the comment "It's this kind of relationship that creates new ideas and imagination. Let's think of what actions to take to explore the kinds of issues and themes we can share within our relationship." The discussion progressed through the partnerships that we had created.

As the Indian participants listened to this, a feeling seemed to spread among them that though there are significant differences between the cities and villages in India and Japan on the surface, they may be able to learn from some of the solutions for the same kinds of issues in Japan or methods to prevent the problems in the first place. Based on this thought, we explored the similarities in the development of cities and villages in Japan and India, trying to find new ways to solve problems.

Nitin Gachhayat is a co-founder of Drishtee, which has established itself as a pioneer of India's BoP (Base-of-the-Pyramid) business, and he started to show interest in the Japanese case study of sustainable tourism in rural areas. Tourism is a major element in rural development in India and also an area that Drishtee wants to further develop.

Akio Hayashi, former manager of the NPO BEPPU PROJECT, shared his own experience. "Development starts by discovering what's already there in that local area. You don't need to bring in something from the outside. For example, with the vocational training Drishtee already provides, you could start sending out information little by little and make it into a brand. It can even be just writing about your daily activities or the local history on an internet blog. Brands are just created along that line."

Nitin Gachhayat, co-founder of Drishtee, and Akio Hayashi of the BEPPU PROJECT, discussing ways to apply Japan's region planning model to the cases in India

Takashi Kawazoe is the president of Carepro, Inc., which provides "one-coin (500 yen) medical checkups" for 33 million people in Japan who have not had a checkup in the past year. On the spot, he began to suggest a partnership to an Indian hospital manager, who then started showing interest in Kawazoe's simple health check system that does not require the presence of a doctor.

Yusuke Ohashi is the representative director of the NPO Asuiku, which supports children's education, and he explained its educational program for children in low-income families implemented in the Tohoku region of Japan. Despite the differences in the social environment in Japan and India, education and medical services are issues that weigh heavily on the both societies, with definite solutions yet to present themselves.

Takashi Kawazoe of Carepro proposing a partnership to an Indian hospital manager at the workshop on the last day of the program

Rahul Nainwal is the director of iVolunteer, an NGO responsible for deploying long-term volunteers all over India and nurturing leaders through these activities. He shared the importance of "sensing," in other words, the ability to feel what is actually happening in the field, and "visioning," the ability to dream of the future. The Japanese members then discussed what they could do in the next program. There was lively discussion about the possibilities of training youth leaders together with Asian countries, and partnering with Japanese companies or Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) programs.

Rahul Nainwal, director of iVolunteer, which connects urban workers with NGOs in rural villages

How can we talk about problems of different societies together?

The process of understanding different cultures, especially when it comes to discussing delicate issues as social entrepreneurs, always leads to one side revealing their ignorance with regard to the "less-advanced" side. The labels "developing countries" and "developed countries" are suggestive of linear development, but it seems the less people have, the more sensitive they are to how these words are used.

For example, the sanitary conditions in India are poor compared to those in Japan. But who can assert India's environment to be "dirty?" This cannot form the basis for constructive discussion. Aya Kubosumi, chief researcher at the Research Institute of Behavior Observation, Osala Gas, is a professional in observing such differences in cultures, and she says it is possible to change relationships just by avoiding the use of negative words.

But then again, you need to understand the social context to judge what is negative or positive. The question "Why can't people choose their jobs in India?" may come across as ignorance of the caste system, or it could be seen as a question capturing the positive development of India, recognizing the gradual increase in the freedom of choice in employment. Japanese people tend to think of India as a whole, but it is a big country with a population of more than a billion people. There is no need to bundle it up into one area with one uniform image.

Broadening our imagination by visiting remote areas and cities

In the hope of broadening our imagination by visiting remote areas and cities, we decided to travel to two cities and one rural area. Since it would be difficult for Japanese people to suddenly go and visit a remote village, Drishtee helped us out with this.

Drishtee is a company that decided to specialize in building a rural distribution network in India, which would seem to be the complete opposite of a normal business strategy. Drishtee strived each day to optimize its network using information and communications technology, and finally built a logistics solution for delivery in northern India. All of these activities were in an effort to dissolve the dilemma of the impoverished and residents in remote areas having no choice but to buy all products and services at higher prices.

Siddhartha Shankar, the director of Drishtee, said, "NGOs, government, companies, and every kind of player would visit those places, never to return. Since we're involved in distribution business, we visit regularly. That generates a trusting relationship with the villagers." The place we traveled to was a small city called Mathura, a four-hour bus ride from Delhi, where we visited a Drishtee "branch," which serves as the main artery of their business. Every day, daily essentials ranging from food to water and sanitary goods are distributed from branches like this through their capillary-like network, reaching the most remote areas of India.

Participants visiting the Drishtee Mathura branch, engaged in lively exchange

(Left) Drishtee Mathura office, (Right) Retailers supported by Drishtee

(Left) Drishtee's computer classroom, (Right) Computer class students talking about their dreams

In India's IT city Bangalore, many players who "graduated" from the flourishing IT companies dive into social enterprises. Thus, it is no coincidence that the Ashoka foundation, Social Venture Partners (SVP), and other globally recognized social corporations have their India branch in Bangalore. Ranging from think tanks studying social innovation to investment funds, business methods and methods to solve societal problems are now merging.

In Delhi, we faced the issues of deep-rooted poverty and the dignity of the impoverished. We visited an NGO called Goonj, which provides second hand clothes to the poor, but not for free. As payment, they ask the people to participate in development of community assets such as the construction of bridges, irrigation, or wells. Goonj representative Anshu Gupta said, "Begging is an urban custom. It would never be accepted in rural areas. The poor in rural areas would rather buy things instead." What Anshu had provided was not simply second hand clothes for people to wear but a means for people to keep their dignity. The poor who take part in community development are both praised for their contribution and able to receive clothes.

(Left) Anshu Gupta, (Right) Women sorting the second hand clothes

(Left) Second hand clothes packed to be sent to rural areas, (Right) Used clothes recycled without waste

What we witnessed as we traveled back and forth between the cities and rural villages, or central and remote areas, was not simple linear development progressing from developing country to developed country. One of the examples that illustrated this was perhaps the AyurVAID hospital we visited in Bangalore. They were trying to provide new medical services, affordable to the poor, by redefining the possibilities of traditional ayurvedic medicine. They brought statistical management into the world of traditional medicine to help attain a certain level of quality and thus provide effective services for chronic illnesses that also afflict the poor. What struck many of the participants was, besides the actual innovation in traditional medicine, the reality that society can be changed through something that may be overlooked but is already there.

(Left) AyurVAID hospital office, (Right) Rajiv Vasudevan of AyurVAID hospital

Identifying different possibilities from different societies

Listening to the dialog at the workshop held on the last day, it was clear that the Japanese participants were engaged in discussion with the basic approach of making an effort to understand the Indian societal context, if only a little.

Going back and forth between the cities and rural villages of India had also generated a shared sentiment among the participants. "Perhaps, some of the advanced cases in Japan are outstanding examples on a global level also, and maybe they could be applied to India. If India is heading towards problems Japan has already experienced, perhaps we could help prevent them beforehand, or rather, maybe the problems experienced are the same all over the world, and we could solve them quicker by bringing our ideas and resources together, transcending borders."

Japanese and Indian participants making group presentations

Discussing about Japan-India cooperation in the future

This program aimed to a) serve as an opportunity for Japanese social entrepreneurs to expand their imagination beyond borders and b) produce future-oriented dialog and partnerships through people-to-people exchange. The result is just as I have described, but the key was that the diversity of the participants from Japan and India had provided a certain direction and unity within the shared theme of "urban cities and rural villages."

This had stimulated the participants' imagination and produced a deeper insight into social context, while also becoming the source of dialog and partnership. The topics raised at the workshop were spontaneous and not predesigned. Meanwhile, though many of the participants spoke little English and communication was conducted with the help of interpreters, we were able to have creative discussions, and ideas did not simply end as ideas. Some of the generated partnerships are now moving forward.

The need to change our attitude and get involved

"Society will not change." "Japan has stopped growing." Perhaps we have been too caught up in "linear" thinking. What we witnessed in this exchange program is the reality that the things we take for granted can provide new perspectives for our neighbors. We also sensed the emergence of the feeling that we may be able to change society by seeing the differences with our neighbors that may open or shut our eyes. Society is starting to move now, changing through each and every encounter that transcends all frameworks.

As the moderator, while acknowledging my own shortcomings, I do feel that this program had full of possibilities and at the same time many problems that needed to be addressed. It had been a difficult task to meet the expectations of both the Indian and Japanese sides, make appointments in India, and escort everybody safely to our destinations on time. There had also been the challenge of facilitation and explaining in English where necessary. I was so exhausted that the couple of days after the program seem to be a blur in my memory. Even so, if we think of this program as the starting point for things to come, I believe we will see results in the future. If there is one thing that we should consider for the next step, it would be the need to change our attitude.

We all need to be aware that these things are directly related to us and we must engage in discussions. We need to go places ourselves and understand our neighbors. I believe this is the only way to transform Asia's diversity, with its challenges and possibilities, into a source of creativity that can change society.

All the participants were able to spend the last day fully engaged in the program, and that process was supported by their words and actions full of commitment. I would like to express my sincere appreciation to all involved.

Tetsuo Kato

Tetsuo Kato

Tetsuo Kato was born in Osaka in 1980. He serves as the managing director and management consultant of World in Asia, a general incorporated association which invests in social entrepreneurs aiming to reconstruct the Tohoku region. As an entrepreneur and business development professional, he has been involved in social venture reform, in addition to scale-out planning and its practice for approximately 10 years. Kato engaged in the regional implementation of entrepreneur training models at the non-profit organization ETIC., and then led the restructuring of the non-profit organization G-net as its director. He travelled to 12 countries from 2009 to 2011, after which he published his case study on social innovation titled Henkyo kara sekai o kaeru (The World is Changed from its Frontiers).

Keywords

- Culture and Society

- Arts/Contemporary Arts

- Medical/Health

- Economics/Industry

- Education/Children

- Social Securities/Social Welfare

- NPO/NGO

- Social Enterprise

- Japan

- India

- Social entrepreneur

- World in Asia

- New Delhi

- Mathura

- Bangalore

- Ayurveda

- Rajiv Vasudevan

- Arathi Laxman

- Oita

- Yufuin

- Beppu

- Delhi

- Social entrepreneur

- NGO

- BOP business

- Drishtee

- BEPPU PROJECT

- Akio Hayashi

- Takashi Kawazoe

- Carepro

- Asuiku

- Yusuke Ohashi

- iVolunteer

- Japan International Cooperation Agency

- JICA

- Aya Kubosumi

- Osala Gas Research Institute of Behavior Observation

- Caste system

- Mathura

- IT

- Goonj

- Ashoka foundation

- Social Venture Partners

- SVP

- AyurVAID hospital

Back Issues

- 2025.12.19 Echoes of a War Unli…

- 2025.6.24 Exclusive Interview:…

- 2025.5. 1 Ukrainian-Japanese I…

- 2024.11. 1 Placed together, we …

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.5. 2 People-to-People Exc…

- 2024.2.19 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2024.2.19 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2023.4.24 The 49th Japan Found…