The 49th Japan Foundation Awards

―Building Bridges Across Differences― <4>

Goenawan Mohamad - Award Commemorative Lecture

April 24, 2023

【Special Feature 078】

Special Feature: The 49th Japan Foundation Awards ―Building Bridges Across Differences― (for summary on special features, click here)

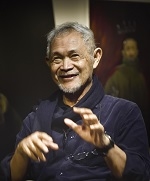

Goenawan Mohamad is a leading Indonesian intellectual who has long played a leadership role in the country's democratization movement. He published the weekly news magazine Tempo and worked as a spirited journalist who emphasized the importance of liberty and democracy. After retiring from the front line, he is still engaged in literary activities such as essays, poems, plays, novels, and paintings. The world has since listened to his insightful words on freedom of expression, religion and culture, and ethnic identity.

The relationship between he and Japan began in 1997, when he was invited as one of the fellows of the Asia Leadership Fellow Program (ALFP), a joint program of the Japan Foundation and the International House of Japan (I-House). Afterwards, he deepened intellectual exchange through frequent invitations by Japanese academic conferences and study groups.

Asia, which accounts for half of the world's population, is currently experiencing remarkable economic development and globalization. On the other hand, some people indicate negative sides of widened gap and deterioration of democracy. Here, we introduce Goenawan Mohamad's thoughts behind his statements on "culture" and "difference" in the current Asia, he told us at his award commemorative lecture.

Goenawan Mohamad (photo courtesy of the lecturer)

Goenawan Mohamad (photo courtesy of the lecturer)

A new look at the notion of "culture" and "difference"

Let me begin with a confession. The news that I am one of the recipients of the Japan Foundation Awards of 2022 overwhelmed me.

Apparently, it took much of my time to be overwhelmed.

I spent two weeks preparing myself for the trip to Japan. I took a PCR test, recovered my old thermal underwear for the October weather, bought a new jacket, attempted to make a Double Windsor knot, etc.

In short, it was a big production.

To come to visit Japan again after more than 10 years gave me a tremendous thrill. Japan never stops intriguing me. But it is neither for its beauty (as suggested poetically by Kawabata Yasunari in his Nobel Prize speech) nor for its ambiguity (as discussed by Ōe Kenzaburō in his discourse of Japan's predicament as a nation). I think Japan intrigues me, or better, frustrates me, because I do not speak or read Japanese, and yet I find the echo of the words in Japanese writings constantly enticing, even in translation. Therefore, I always love to be close to it ― while knowing how deep the rift is.

Coming from Indonesia, I find the well-known Japanese cultural homogeneity both astonishing and unexplainable. Indonesia is famous for its diversity, of which I will speak later, and many parts of Asia have a similar trait. But Japan shows no obvious centrifugal anxiety, and I often wonder why.

Particularly today, when we live in a time of culture wars. The word "war" may be hyperbolic, an exaggeration of the notion of "Kulturkampf" in the German history of the 19th century.

The "Kampf", or the strife, took place when the State under Bismarck was drawn into a confrontation with the Catholic church on matters of educational policy.

Today I am using the word to describe events like the current Iranian upheaval, when there is a clash between two camps: in the upper floor are people holding strict Islamic values regarding women's behavior; in the lower parts of the society are those who find themselves oppressed by the religious precepts. The hijab, or the head scarf, is no longer a piece of cloth; it has become the center of the conflict, in which at least three young women were killed.

What is happening is both horrific and inspiring.

Like war, it is about bravery, life, and death.

From the Award Commemorative Lecture (photo by Sankei Kaikan)

From the Award Commemorative Lecture (photo by Sankei Kaikan)

I think it also is the case of the repression of underclass women in the US. They are to be criminalized when they choose to have an abortion. For them, the issue is not between "pro-life" and "pro-choice". For them, to be able to choose not to have a child is a method for survival. Meanwhile, the majority, hoisting the banner of Christianity and "American values", believe that such a position is a danger to the American identity. The rejection of it is perceived as a battle against a polluting element.

We see the rise of "purism".

"Purism" is a drive against what is perceived as alien intrusion in one's behavior and belief. "Purism" is an impulsion to purge "the other" from the "self" and prevent hybridity in the social. It is a kind of cultural paranoia.

I remember The Crucible, a play by Arthur Miller, which to me is an authentic narrative of fear and intolerance. In the third act, one character, Judge Danforth, says some threatening words:

"This is a sharp time, now, a precise time ― we live no longer in the dusky afternoon when evil mixed itself with good and befuddled the world."

Underlying this mindset is a rejection of ambiguity ― refusing to live "in the dusky afternoon when evil mixes itself with good." It is purism par excellence.

Oftentimes the presence of religion heightens this, as people are desperate for clear precepts and powerful formulas. Increasingly, religion is no longer a private worship in silence; it has become more and more institutionalized. Finally it transforms itself into and merges with the notion of "culture". No wonder that in a short piece on the definition of "culture"*1, published in 1949, T.S. Eliot reminds us that "[N]o culture can appear or develop except in relation to a religion."

Religion links itself with the eternal. Immediately, "culture" becomes its shadow ― and people forget that "culture" is a continuous creative production. It is an undetermined process.

But the error of seeing "culture" as a constant coherence is not only the outcome of its relation with religion. Different forms of colonization, European colonialism in Asia was the most obvious, insisted on creating "taxonomy" in which "culture", as a continuous process, was broken into different genres, each with its clear and distinct demarcation.

The narrative of Indonesian diversity is a case in point. Indonesian diversity consists of units called "sukus." Each has its own myths and symbols, even languages. But it is not clear what is the origin of sukus or units; an anthropological study may reveal that a suku's identity and its living space are not natural phenomena. It was constructed by Indonesian politics of taxonomy and mapping. It is a geography drawn by the state. It is like drawing a city from a tower; as a matter of practicality, it simplifies the intricacies of the real world.

Let's look at Java. The Dutch colonial regime in the 19th and 20th century called or labeled the territory 'X' "Java" as if it was a single entity. In the real world, it consists of more than one language and aesthetic tradition. But the powers-that-be rule that one of them is to be put in a superior position, and the rest are insignificant.

The nationalist rhetoric about the way colonialism maintained its grip ― which is "divide and rule" ― is apparently not an empty one.

I share what Edward Said says in his Culture and Imperialism, "Imperialism consolidated the mixture of cultures and identities on a global scale. But its worst and most paradoxical gift was to allow people to believe that they were only, mainly or exclusively, white or Black or Western or Oriental."

The old imperialism disappears as a brute political force, but its discourse on "difference" has re-emerged in new forms of control. "Difference" has become an institutionalized assortment. Religious doctrines and secular interests encourage the current human division by promoting "identity politics."

What I see is widespread politics of paranoia, a serious menace to what humankind has in common.

The challenge of our time is to undo all this, by looking more at the creative impulses of culture, and not its identity.

- *1 Notes towards the Definition of Culture by T. S. Eliot

The lecture is also be available on the official YouTube channel of the Japan Foundation. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yTeGEPleysE

October 20, 2022

Lecture at the International House of Japan (Tokyo)

Related Articles

Related Events

Back Issues

- 2025.12.19 Echoes of a War Unli…

- 2025.6.24 Exclusive Interview:…

- 2025.5. 1 Ukrainian-Japanese I…

- 2024.11. 1 Placed together, we …

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.5. 2 People-to-People Exc…

- 2024.2.19 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2024.2.19 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2023.4.24 The 49th Japan Found…