The Delights of Performing Rakugo in English and Writing Novels in Japanese

Shinoharu Tatekawa (Rakugo performer)

David Zoppetti (Novelist)

J. MaXwell Powers (Moderator)

Shinoharu Tatekawa is a rakugo performer who studied at a U.S. university, and practices rakugo in English. You may be familiar with him from his Wochi Kochi Magazine essay series. David Zoppetti is a Swiss born novelist living in Japan who writes novels in Japanese. A discussion was held on June 8 between the rakugo performer and the novelist, who express themselves in a language other than their mother tongue. Under the witty guidance of J. MaXwell Powers as the moderator, discussions took place over 90 minutes covering the attractions of their respective activities of performing rakugo in English and writing novels in Japanese. In this article, we bring you a summary of the scene at the hall, where the discussions were met with great laughter and enjoyment.

JFIC Event 2015 "Wochi Kochi Magazine" Shinoharu Tatekawa and David Zoppetti talk event, moderated by J. MaXwell Powers (June 8, 2015 at the Japan Foundation JFIC Hall "Sakura")

I want to express the true taste of rakugo even when performing in English - Shinoharu Tatekawa

J. MaXwell Powers (MP): To begin with, Shinoharu, tell me how you first discovered rakugo.

Shinoharu Tatekawa (ST): Sure. I discovered rakugo around my third year at work. At the time, I actually had no interest in rakugo at all. I encountered rakugo at a one-man show of Shinosuke Tatekawa in Sugamo that I happened to attend casually as one of those "try it once in your life" experiences, but it ended up impressing me a great deal. After some time the master Shinosuke Tatekawa, who was performing on the dais, seemed to disappear. Or, to put it more accurately, it felt as though he disappeared because the characters he described in his rakugo story became almost tangible in my mind. I fell in love with rakugo in that instant, thinking to myself that "I never realized such an art existed!" Because of this meeting, I quit my job one year later and became a disciple of Shinosuke Tatekawa.

Shinoharu Tatekawa describing how he discovered rakugo

David Zoppetti (DZ): I went to see Shinoharu's one-man show in May because I wanted to see his performance once before today's discussion. I was also able to experience that sense of the performer "disappearing" at that time. In the beginning, Shinoharu was right there on the dais. But one by one he breathed life into the characters in the story, and before I knew it, Shinoharu had seemingly disappeared from in front of my eyes.

MP: I also went to that one-man show. As I listened to his rakugo stories, I wondered what it would be like for the stories to be performed in English.

ST: Let's say I do a story that features a husband and wife. In Japanese, listeners understand who is speaking, the husband or wife, without any need to change my voice. However, in English, I'd have to change my voice so they would know the difference between a man and woman. So I have to overact to a certain extent.

DZ: I listened to rakugo in English for the first time on the CD included with Shinoharu's book, Dare demo Waraeru Eigo Rakugo: Rakugo in English [Rakugo that anyone can laugh: Rakugo in English]. When I learned that you could enjoy rakugo, which I had considered to be an art form of Japanese classical performing art, in English, I wanted to hear what the performer had to be careful about when performing it.

ST: I do change my voice to differentiate each character, but I try not to overdo it. That's because I want to retain the traditional flavor of rakugo. But gestures can be a challenge. For instance, there's a scene, in which a Buddhist priest says, "Chinnen, come over here," to call over his disciple. The gesture of turning the palm downward to call someone over is unique to Japan. In the U.S., people turn the palm upwards and move their fingers. But if I use the U.S. custom of calling with the fingers just because I'm doing rakugo in English, then it makes the priest look silly. So in that situation, I limit my physical actions.

DZ: For the gesture of writing a letter, rakugo uses a tenugui cloth and a fan. Do you use a horizontal writing gesture when performing rakugo overseas?

ST: No. I use a vertical writing gesture to show how that is the way we write in Japan. At the show in Singapore, I heard children shout, "That's wrong!" Speaking of the reactions of the audience, the behavior of people overseas is more direct and free. In comparison, Japanese audiences are very careful, thinking "when should I laugh" or "it might be embarrassing to laugh now."

DZ: When I went to see Shinoharu's one-man show, I also caught myself checking what those around me were doing. You can get overly concerned that others might wonder why you laughed at a certain point.

ST: Overseas, people don't worry about those around them. They just laugh at whatever situation they think is funny. Japanese people are not really able to do that. I want to tell the Japanese audiences not to worry about people around them, because I want everyone to react freely and laugh when they like.

DZ: You should say that in your introduction.

ST: You're right. Why don't I say it at every time I perform?!

Writing novels in Japanese is an irresistible pleasure - David Zoppetti

MP: David, what was the reason you started writing novels in Japanese?

DZ: Thirty years ago, when I started studying Japanese on my own, I borrowed the novel Akan ni Hatsu [Suicide in Lake Akan] by Junichi Watanabe from my girlfriend at the time, who was Japanese, and read it while constantly referring to a Japanese-French dictionary. Later, as I read several more Japanese novels, I began to feel that I could write one as well, or rather, I was developing the delusion that I could. The book I wrote as a result was Ichigensan.

MP: I've heard that you write your novels by hand.

DZ: I do. I am a hopelessly analog person. While my handwriting is horrible, I am completely in love with the feeling of writing in Japanese and filling in the boxes on Japanese manuscript paper. Sliding the fountain pen across the paper gives me a strong sense of satisfaction.

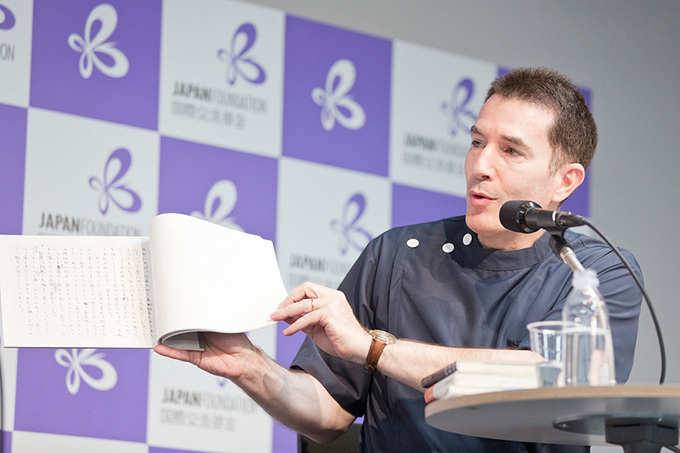

David Zoppetti holds up one of his manuscripts as he speaks.

MP: Is the number of foreign authors who write novels in Japanese increasing?

DZ: Works written in Japanese by foreigners for whom Japanese is not their native language is called "cross-lingual literature." So apparently that makes me a "cross-lingual author." When I made my debut in 1997, the only cross-lingual author other than me was Hideo Levy, who is from the U.S. Now there are quite a few more. The most famous author is Yang Yi, who is originally from China and the first foreigner to win the Akutagawa Prize, for Toki ga Nijimu Asa [A morning when time blurs]. Other such authors include Wen Yourou, born in Taiwan, Shirin Nezammafi from Iran, a poet from the U.S. named Arthur Binard, and the Canadian essayist John Gathright. While the number of such authors is still few, we are getting to the point where the Japanese language no longer belongs exclusively to the Japanese people.

J. MaXwell Powers leads the discussions.

MP: Would you be able to, for instance, translate one of your Japanese novels in another language?

DZ: No, I wouldn't. I tried to do it once when I was asked to translate Ichigensan into French by a publishing company there. Unfortunately, my French has dropped to the secondary school level, and when I read my own translation, it did not sound like French at all. So far my work has been translated into Korean and English, but I have no desire to translate it myself.

ST: Japanese has unique words and expressions which I imagine are hard to translate into other languages.

DZ: Ichigensan was translated into English by an American professor who specializes in English literature. We had a number of different opinions about how to translate during our correspondence together.

ST: Was it because you didn't feel the translation was just right?

DZ: The way he translated into English made me feel that it was slightly different from what had I intended to say. However, as long as the novel itself is solid, then I think it will work as a piece of literature even if there are slight deviations in the translation.

MP: What about humor? Do you think there is a common understanding of it throughout the world?

MP: What about humor? Do you think there is a common understanding of it throughout the world?

ST: That's a good question. While American jokes are funny when heard in English, they can sound a bit too genteel when translated into Japanese. So I think there is definitely something that is lost in translation. In the case of rakugo, puns are just impossible. The phrase "futon ga futtonda" (the futon flew away) is not a pun in English, though it is in Japanese. And the punchline in rakugo won't work when translated into English, so you have to drop hints before you get there. But in the end, the punchline often becomes a bit too explanatory.

DZ: Shinoharu, in your book you said that much of the humor in rakugo evokes laughter using the weakness and hopelessness of people. Do you think human weakness and foolishness work the same way when you perform in English?

ST: Yes I do. Basically, I think that the kind of human weakness and foolishness that appears in rakugo is the type where people pretend they know something they don't, or try to come up with a plan to get rich quick. Rakugo does not say those actions are bad. The philosophy of rakugo is often that while people give in to their desires and act stupidly, that is also one of the appeals of being human. People overseas understand that as well.

DZ: It must be universal.

ST: I think so. The classical rakugo we are doing these days consists of stories dating from 300 years ago. Japanese people from 300 years ago laughed at those stories, and Japanese today are laughing at the same ones. I believe that stories that have lasted 300 years are universal enough to be understood by people overseas as well. It is actually more difficult to translate modern rakugo into English.

Novels should be read in paper book form - David Zoppetti

Rakugo should be seen live - Shinoharu Tatekawa

MP: These days, young people have short attention spans and content quickly grows old. David, do you struggle in any way with regard to universal concepts when writing your novels?

DZ: I happen to love traveling, and I published a collection of essays entitled Tabi-Nikki [A Travel Diary]. I actually wrote a sequel to it, but the publisher turned it down. When I asked why, they said it was because Japanese readers, having experienced the Lehman Shock and 3/11, no longer wanted to read about travel. It made me conscious of the flow of the times, which is to say that the situation has changed.

MP: David, have you yourself felt anything change with Japanese readers?

DZ: I have lived in Japan almost 30 years, and as a novelist, the biggest change I've sensed is there are more alliterate people among the Japanese. To be precise, Japanese people read less and less works of literature. When I first came here in 1983, there were between 15 to 20 people reading books in my train car on the Yamanote line. I saw that and thought, "Japanese people are serious readers." Today, almost nobody reads books on the train. Almost everyone is concentrating on smartphones, games, or listening to music.

ST: Smartphones are an issue for us as well. There are people who take pictures with their smartphone cameras when we perform rakugo as a sideshow at events. Recently people have also starting shooting video. When I ask what they plan on doing with the video they say, "It was so fun that I want to show it to my friends." But I feel that the fun of the moment can definitely be communicated to the other person better by describing in words what you actually see there yourself.

DZ: I agree.

ST: I can't help feeling that, strangely enough, experiencing the atmosphere of the moment has become a rare thing.

DZ: It is hard for me to get my manuscripts printed these days because nobody buys literary magazines anymore. If I were allowed to ask something of the Japanese people, it would be for them to read novels in paper book form. I want them to rediscover the pleasure of reading while turning the paper pages.

ST: I fell in love with rakugo by hearing my master perform it live. I wish for everyone to actually go there and experience the atmosphere of a live performance.

(Editor: Sayuri Saito, Photos: Kenichi Aikawa)

(Editor: Sayuri Saito, Photos: Kenichi Aikawa)

Shinoharu Tatekawa

Shinoharu Tatekawa

Rakugo performer Shinoharu Tatekawa was born in Osaka and raised in Chiba prefecture. He joined Mitsui & Co. in 1999 after graduating from Yale University. In his third year of work, he chanced upon a performance by Shinosuke Tatekawa, and decided to become his disciple after quitting Mitsui. In 2002, he was accepted as the third disciple of Shinosuke Tatekawa. In January 2011, he was promoted to futatsume (the second highest rank). He performs classical and contemporary rakugo works, as well as rakugo in English, and has even performed in Singapore. Dare demo Waraeru Eigo Rakugo: Rakugo in English [Rakugo that anyone can laugh: Rakugo in English] (Shinchosha) and Anata no Purezen ni "Makura" wa Aruka? Rakugo ni Manabu Shigoto no Hinto [Does your presentation have an "introduction"?] (Star Seas Company) and Jibun wo Kowasu Yuki [Courage to destroy yourself] (CrossMedia Publishing).

![]()

David Zoppetti

David Zoppetti

David Zoppetti is a Swiss born novelist who has lived in Japan since 1986. He studied Japanese at the University of Geneva before completing his degree at the Faculty of Letters of the Doshisha University. He worked at TV Asahi from 1991 through 1998, during which time he won the Subaru Literary Prize in 1996 for his novel Ichigensan. He was also a candidate for the Mishima Yukio Prize for Areguria [Alegrias] (Shueisha) in 2000 and won the Japan Essayist Club award in 2001 for his Tabi-Nikki [A Travel Diary] (Shueisha). His other works include Inochi no Kaze [The Winds of Life] (Gentosha) and Fuhou Aisai-ka [An illegal husband in love] (Shinchosha). He currently works as a reflexologist under the RWO-SHR Health Method in addition to writing.

![]()

J. MaXwell Powers

J. MaXwell Powers

J. MaXwell Powers was born of an American father and Japanese mother, and comes from Oakland California, where he enjoyed Japanese manga from a young age and started teaching himself Japanese at the age of 15. He later came to Japan as an exchange student and studied International Politics at Sophia University. He is currently active as an actor and narrator in commercials, TV programs, and films while working as a translator and interpreter. His hobby is studying the differences in how to think in the Japanese and English languages.

Back Issues

- 2025.11.14 Stories from Both Si…

- 2025.10.24 Dialogue through Ani…

- 2025.6. 9 Creating a World Tog…

- 2024.10.25 My Life in Japan, Li…

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.5. 2 People-to-People Exc…

- 2024.5. 2 People-to-People Exc…

- 2023.12. 7 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2023.6.16 The 49th Japan Found…