The 49th Japan Foundation Awards

―Building Bridges Across Differences― <2>

A Commemorative Talk Session by Robert Lepage and Takahagi Hiroshi

June 16, 2023

【Special Feature 078】

Special Feature: The 49th Japan Foundation Awards ―Building Bridges Across Differences― (for summary on special features, click here)

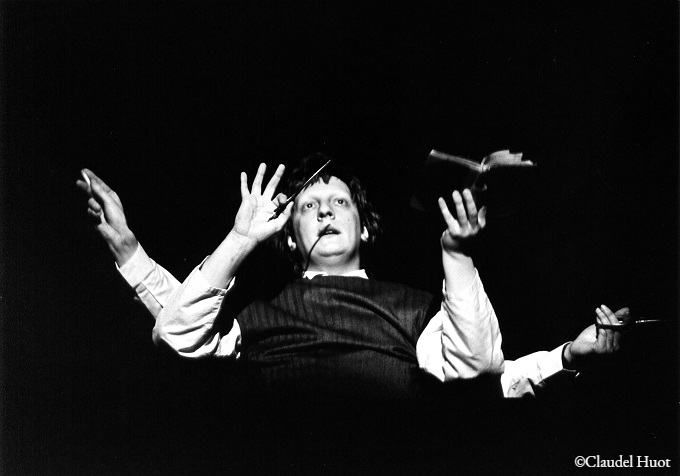

Born in Quebec, Canada, Robert Lepage is a versatile performing artist, who also plays a role such as a director, an actor, a playwright and a film director. His unique productions that actively incorporate the latest technologies have received a high evaluation from all over the world, and he has worked in many genres other than theater, including operas, concerts, films and the circuses.

Lepage also has a long history of interactions with the Japanese theater world. He continues for a long time to be a constant source of new surprises to Japanese artists and Japanese performing arts. Lepage says that he himself is also deeply influenced by Japanese traditional performing arts and his previous visit to Hiroshima.

In this dialogue between Lepage and Takahagi Hiroshi, director of Setagaya Public Theatre supported by Setagaya Arts Foundation, both of whom have had a long friendship with each other for as long as 30 years, Lepage talked about his encounter with Japanese culture, an influence he had from Japanese culture, and also about his ideas about theater as a form of expression.

Takahagi:

You first came to Japan in 1992, and then I assisted your visit to Japan several times.

Today, I was told to ask you about "how Japanese culture has impacted your work", so I would like to start by asking about your first encounter with Japanese traditional culture and the area around here specifically. Also, there is a play which attracted lots of attention in terms of "cultural appropriation" in Montreal, Canada in 2018, two years prior to the pandemic of COVID-19. Therefore, this dialogue will be a good opportunity to ask you to talk about something about that. You always speak very consistently about culture and arts and the position of artists, so I would like to hear something about that at the end of our dialogue today.

Let's start by asking about your first encounter with Japanese culture. At the award ceremony, you said, "I first saw Kabuki at the age of 17," and "I was very influenced by Kabuki." What made you so interested? Were you influenced by the actors, or the performance, or the scenic art? Could you tell us a little more specifically about which part of Kabuki you were interested in?

Lepage: I was seventeen years old. I was studying at a theater conservatory in Quebec City. I had a knowledge of Japanese culture, a very small knowledge, all the usual clichés about Japanese culture. I knew a lot about Japanese anime and Ultraman, for me, that was Japan. When I was seventeen, I was part of the committee at the conservatory that would organize, when there would be a foreign company visiting Canada, I would be the one who would organize the tickets to go and see the performances.

So we went to Montreal. I was studying in Quebec City, but we went to Montreal to see the Grand Kabuki that was performing in 1976. They were doing a North American tour. Among the different plays, there was the story of the fox, and it was performed by Ichikawa Ennosuke III, and it was a complete shock for me when I saw that because, up until then, theater was a very talkative, literally thing, and I was desperate to see something that would speak to me through my senses, all of my senses.

Although it was a very traditional form of theater for Japan, for me I could see the traditional side of it, but I could see the modern side of it. It was still very alive, and it felt complete, the experience for the spectator was complete. And I didn't understand everything because it was spoken in Japanese, the kind of ancient Japanese of Kabuki, so it was even more difficult, but I understood everything. For me, I thought that this is the best communication possible in the theater with the audience. It was a total experience, and it was beyond anything I had seen before.

It also seemed to have something very baroque about it, in the sense that it was all kinds of styles of things, but it all worked. It was all coherent and it was all done very elegantly, but it was baroque like some funny things, some moving things, some spectacular things, some magic, some spiritual things. It was all kind of mishmash of all sorts of things but extremely well controlled and orchestrated. And up until then, the theater of the West was very bland, very one-sided. Everything has to look as if it comes from the same theater school, so it's like one idea. But this Kabuki was like three dimensional for me. That was of course my impression as a young, 17-year-old person who didn't know much about theater at that time.

And also, up until then, the theater I had seen was always psychologically motivated. It was all about the psychology, the psychology of the character, the psychology of the epoch, but Kabuki was poetry. It was a story told in a poetic manner, and it had a dimension of the size that did not evade psychology, but psychology wasn't the main thing. The main thing was the poetic storytelling and that for me was very moving, and very very exciting.

I think the main thing is the fact that it seemed that Japanese theater did not seem to have a fourth wall, and that's the problem when you go to the theater in the U.S. or in England, or even in France. There is an imaginary wall and there is the audience, and the emotion is here on the stage, and you are the voyeur (viewer) of the emotion. It was the first time I could see that the emotion in Kabuki was in the room, it was in the spectator, not on the stage and there was no fourth wall. So at one point, the actor only continues to play if the audience screams the name, and it invites the audience to come on stage in a certain way. I've never seen that in my life because, in general and still today, the Western world theater is, "Please don't make any noise", "Please don't exist, we are doing something". Pardon my expression, but it is very masturbatory, so for me, that was very liberating when I saw that.

Maybe one last thing about that experience, my first experience at 17. For the first time, I didn't feel like an idiot in the theater and the show did not consider me as an idiot. It showed everything, we saw Kuroko running. It says, yes, we all agree it, this is theater, this is not reality, so it has confidence in the intelligence of the audience. As in the Western world, up until that moment, the people pretend that this is life, this is reality, this is for real. It's not for real, it's theater so there is that illusion that I always feel alienated when I see a play, but when I saw Kabuki, I felt like oh, my imagination is solicitated.

Takahagi:

Listening to your story about how Kabuki can make such an impression on a 17-year-old high school student, I want the Japan Foundation to continue Kabuki tours overseas. Although there is no one in the audience from the National Theatre of Japan today, your story also makes me want to tell them that it is very meaningful to show Kabuki to Japanese 17-year-olds, too (laughs).

Then you started to create your own works and came to become a creator. The Dragons' Trilogy, your breakthrough work, includes an episode of Japanese people, doesn't it?

When you created that work, including an episode of Japanese people, did you draw on your experiences of Kabuki? If that is the case, what kind of characteristics of Kabuki are included in particular?

Lepage: I think even before that, when I started my creative life, I started to do my own stories, I was influenced from the way the stories were told in Kabuki, so when we did The Dragons' Trilogy, of course, The Dragons' Trilogy, which is about Chinatowns, so it's more about the Chinese people of Canada, but there was a little story within that, that included a Japanese woman who had an affair with a military man, which was a reference to Madame Butterfly and all that. So of course, I think that it's once again, the baroqueness of Kabuki, the freedom of using different styles and things and all that and putting in things as long as it's coherent. That for me was the big influence. Of course, it wasn't as influential as when I finally came to Japan in 1992 and got to see and spend more time here, and after that, that had a lot of big which had a much bigger influence on my work. But up until then, I was very interested in that and also, I know it's a lot of translation. You have to know in the 1980s in Quebec, people were very interested in what was coming from Japan. Budo, some Kabuki, but also Japanese movies, music, the Taiko drummers--so a lot of Japanese culture started to come to that part of Canada, and we were very influenced and interested in it, so we would apply it to anything we would create, so became very physical, very musical. So The Dragons' Trilogy is in part influenced by that chapter.

Takahagi: The director of the Japan Foundation, Toronto, mentioned that the Japanese family in The Dragons' Trilogy looked more Chinese than Japanese. So, we said, "We want to invite Lepage to Japan." Around that time, you were staging A Midsummer Night's Dream at the National Theatre in London, and the Globe Tokyo I belonged to at that time, also wanted to host a production from the National Theatre. So, the Japan Foundation and the Globe Tokyo invited you to Japan. You made your first visit to Japan in 1992 at the age of 33. I remember that you went to see Kabuki once again, probably at the Kabuki-za Theatre. So could you tell us about the differences you perceived between the production you saw at the age of 17 in Montreal, and the production you saw at the age of 33 at the Kabuki-za?

Lepage:

Well, of course, the very first day I arrived in Tokyo for the first time. I came in 1992, I ran to the Kabuki-za and Yotsuya Kaidan.

There was one actor who played all the parts, the main parts, and he came on stage at the beginning and there were like big posters with the different characters, and he said "I will play this one, and eventually I would play this, would play that." Then the show started, and it was spectacular. He was amazing, he would change costumes very quickly and it was fantastic. At the end, when he dies, he goes to heaven or goes to somewhere, and a mysterious world, and he is on the edge of the stage, the audience is here, and he is here, and he does his last speech and then it comes up and he walks midair above the audience. I'm crying, it was an incredible experience. It was even more orgasmic.

One of the main differences is that the first time I saw Kabuki, the audience was Canadian but now it was Japanese people. The lights were open a little bit in the room and the people were eating bento box (boxed lunch) and talking and moving, and it did not disturb anything because what was on stage was so colorful, powerful, loud and generous, that whatever happens here. In Canada, somebody would eat a biscuit and the show stops, but the power of what was on stage was overwhelming, so for me that was a big shock.

Takahagi: Was there anything you found particularly interesting in terms of the staging, structure, or roles?

Lepage: I come from a tradition of literary theater. Theater has been associated lots to a play, something that's written, after the director and the actors create, but after in the 1980s, people got more and more interested in non-verbal, non-literary theater. Theater at the beginning is the meeting place of text but also of architecture, of painting, of visual arts, of costume, of music, of choreography, etc. All the forms, creative art forms are invited to tell the story, but I've been accustomed to a theater that only relies on text and anything you do outside of text is decoration. It's not storytelling. So for me, that's the great reconciliation with theater when I started to see Kabuki, Kyogen, Noh and eventually other forms of theater that seemed to have that invitation to other artists to come and participate in the storytelling.

Takahagi: Actually, the week before last (October 7, 2022) at the Tokyo Festival, there was a production called The Scarlet Princess staged by a Romanian director, a work based on the script of Tsuruya Namboku IV's drama "Sakura Hime Azuma Bunsho." Would you be interested if you were asked, "Are you interested in trying to stage a Kabuki script?"

Lepage:

I would be delighted to do that. It's a scheduling problem.

If there wasn't a scheduling problem, I would do it to learn because I accepted to do opera because I wanted to learn from opera. I worked with a rock and roll pop star. I did dance with Sylvie Guillem because I wanted to learn from dance, so I never accept an invitation like that if there's not something for me to grow. I don't have much to teach, I have a lot to learn and that's where it is the most interesting project.

Takahagi: Going back to 1992, when you visited Japan for the first time, you said, "I want to see Hiroshima." I thought that you wouldn't get a full appreciation of the city if you went alone. So, from an izakaya called "Inakaya" in Roppongi, I called a colleague at Hiroshima University who specialized in Shakespearean research, and said to him, "Because a young director, who staged a production at the National Theatre in London will go there, please look after him." I think that then you went off to Hiroshima for one or two days. Could you tell of the time there to us a little?

Lepage: Yes, of course. My first time I came to Japan was a big eye-opening experience and I did many cities and all of that was very fulfilling, but the big shock was really Hiroshima because I was going there as a tourist to see the city where there was the bomb and the devastation and all that, and I discovered a very beautiful, modern, sensual metropolis, and I didn't expect that. I didn't expect it to be so short time period between 1945 and 1992, the speed at which things were rebuilt and the personality of Hiroshima, and the beautiful resilience of the people of Hiroshima or the Japanese people of that area, so that for me was the first big shock.

The Shakespearean scholar who was accompanying me was a man in his 70s and he was himself a Hibakusha (atomic bomb survivor), but only revealed that at the end when he brought me to the train station, and he explained he was a Hibakusha. But before that, he was just like a good guide and during these couple of days he spoke a lot about erotic things which is the last place I thought I'd hear about erotic stories, but to understand the rebuilding, how life starts again when destruction like Hiroshima, how the two bridges, one is like a phallic construction and the other one is more kind of a female. He said because if you want to start life again, you have to give the city some sexual organs. Okay, and so there was a lot of erotic talk and I want to reassure you he wasn't obsessed with sexuality, he wasn't a sex maniac, he was a very serious scholar.

And he told me the story of a young woman who had been disfigured by the bomb, and she was so horribly disfigured that the people around her would hide all the mirrors, there was no mirrors so that she could avoid seeing her face. One day, somebody observed that she was on her pillow and under the pillow there was a little mirror that she was hiding and a lipstick, and when she was looking around and when people weren't looking, she would take the mirror out and she would put some lipstick on, and then people would come and she would wipe it off. He said to me this very strange thing. He said in a war you can disfigure a woman, but you cannot keep her from being a woman. That just hit me. And that was the starting point of The Seven Streams of the River Ota, the whole seven-hour story starts from just that anecdote.

So when he told me at the train station that he was himself a Hibakusha, I understood that he was the one who had witnessed this, that it was a personal thing, but he had been very discrete about it and there is a thing about the Hibakusha, the discretion of what they experienced. Much later on, in 1995, when we did The Seven Streams here at Bunkamura, Issey Miyake came to see the show and we had a conversation. He said, "I myself was a Hibakusha". Issey Miyake was seven years old. He had a little limp and that from the bomb. He said, "I never speak about it", but he said, "I put it in my work". I think Issey Miyake's works are wonderful and beautiful. He said, "My assistant will send you a book, and you will understand what I'm talking about." And a month later, I got a collection of all of his collections of clothing, pictures by Irving Penn, a great American photographer who took pictures of all of his work. There is one of them which is you see the pleating, and the pictures are like a shirt and it's in the mud and it's like skin, and you see that when he was a child, he saw all the horrors of that, the kimono that was burnt in the back of a woman, that he did a dress like that, and of course you only see the beauty. But he said to me, "It's in my work and there's a way to transcend the horror, the negative things in life. There is a way to eventually bring it to a beautiful place, to place a beauty, to a place of art," and I was once again shocked.

So Hiroshima had a big impact on me, not just the time I visited, but through the years, that idea of how to transcend, it's very Buddhist, the Lotus Sutra, out of the murky waters you make a beautiful flower grow.

Takahagi: The Seven Streams of the River Ota is a work which consists of seven acts. Four of them were performed at the Edinburgh Festival in 1994, and subsequently, four acts were also performed at Theatre Cocoon at Bunkamura in Tokyo in 1995. In fact, Bunkamura was planning to put on Seven Streams in Tokyo in 2020, but it had to be canceled due to the pandemic of COVID-19. It was performed earlier this year in Berlin in March, and during the summer in Quebec. Since the work seems to be still alive for a while, it would be wonderful to bring it back to Japan.

Lepage: Of course, there is talk of it may be coming to Japan finally in a couple of years from now, but it would be nice if it was before that, because we're trying to keep the company together and there is some actors now and actresses, and they are starting to be very old.

Takahagi: Your works became more widely known after that, and your Cirque du Soleil work TOTEM was performed in Japan. In such major works that you created, are there any elements that were influenced by Japanese culture, or you can say, "This is actually from Japanese culture"?

Lepage:

I think that a lot of the things I've learned from the Japanese theater in general apply very well in the circus world, because the circus world is a world that is vertical, right? The stories are told vertically, so when you go to the boss of Cirque du Soleil and he says, "What are your ideas?", and you explain there will be something here and then there will be something here, and then something here, and he says, "But what is here?" because it's important for the neck. It's also vertical because it's about like Kabuki, it is the stage, there is mankind, there is all of his dreams, all of his ambitions, all of his inspirations that are there, and there's all of the traps that he falls into. That's storytelling for me and in the circus it's like that. So I think it's easier to tell a story and to apply the rules of Kabuki, the vertical rules of Kabuki, in the circus because of that.

Also, because Kabuki is really what you call a performance in the sportive, it's a sport. It's art but physically and incredibly athletic so it's close cousins with the circus in that sense. The audience expects a great performance, a colorful, inspiring performance but also something athletic, so it's a good place to borrow from Kabuki in the circus.

Also the Kabuki stories, the characters, are a lot human but a lot of them are demigods, people that are humans with a special power, they are hyper human. In the circus, that's what the audience comes to see. They see half gods, they see people give you the illusion that they can fly, they do things that the body is not supposed to do, so that's like the Olympics. You go to the Olympics and people run faster, they don't run as fast as a god, but they run as fast as a demigod. It's like that place where the human being has the illusion that it can extend, and that's what I find interesting in the circus and in Kabuki. The characters are hyper. When Tamasaburo does the shrimp to express, it's from another world, it's not naturalistic.

You will find the same quality in opera also. Opera's characters are larger than life, the singers are larger than life but also the voice is something so large, and opera singing is a scream but controlled. It's a beautiful scream, it's a harmonious scream and you do not scream about banal things, you don't scream about, "Give me the butter!" You scream because it is an essential thing, so it's always hyper. There's something that's larger than life, and that I think it's like Kabuki. Kabuki is often compared to opera in its size and it's interesting also that the first opera is officially in 1608, the beginning of Kabuki is in 1608. I asked the specialist. Quebec City, my city, was founded in 1608, so all the good ideas in the world are in 1608, but these kinds of strange convergences, I guess.

Takahagi: So Kabuki made a substantial impact on you, didn't it? I would like to ask about Japanese contemporary plays. I guess that you saw some of them. Could you share some of your feelings of Japanese contemporary plays, including what you saw and what contemporary artists? Perhaps, you might not be influenced by them.

Lepage: No but there's influence. In the past ten, fifteen years, I haven't seen much contemporary Japanese because every time I come to Japan, I come to present my shows and I do press conferences so I don't have a lot of time. But I see Japanese things abroad, in New York, or sometimes I see a contemporary thing. So a long time ago, I saw the work of (Miyamoto) Amon and the work of Ninagawa (Yukio), and there's always a connection with a tradition but a reinterpretation with the modern codes, and I've always found that very interesting and very exciting. But what I find exciting is, for example, I saw (Noda) Hideki today. Hideki came to my hotel with his suitcase, he was going to Taiwan, who adapted and he only did THE BEE. The production of THE BEE is only three actors and for me it was extraordinary, because a story that takes place today, it's a very modern story, but Noda-san plays the woman, of course, and Kathryn Hunter plays the man, and this tall, very big Scottish guy plays the child. It's completely modern but of course it comes from Kabuki influence things in what he does, and it is he reconciles the idea that you can do things in the theater, you can do things better in the theater because of that freedom.

So if you remember, THE BEE is a novel. It's not a play, it's a novel and it can only be done in the theater, because in the story, which is a bit of comedy, dark comedy, the man rapes the woman every night and he cuts the finger of the child. You can never do that on television, you can never tell that story and show the real violence of that in cinema, in realistic theater, never. But you see a woman who plays the man and she rapes Hideki, who is dressed as a woman, and it's not funny but you accept and you also get the violence, and the big Scottish guy who plays the child gets his finger cut off and you get all the horror, but at the same time, the theater creates the distance, the poetic distance, and I was very jealous when I saw that. I said to Hideki, "You justify wise things, the things you can do in the theater you cannot do elsewhere, and you find the right subject matter." But Hideki comes from Japanese culture and tradition and all of that, and baroqueness, he does that very naturally. We have to impose that in the Western theater, that this idea that in the theater poetry allows you to present things you cannot present otherwise.

Takahagi: You mentioned that you recently created a new theater with a very unique form. I've got a feeling that in terms of the impact that Japanese culture which has made on you, it is perhaps related to the lack of the fourth wall in Japanese culture. In that context, perhaps you could explain a little about the concept behind your new theater, Le Diamant?

Lepage: Actually, "Ex Machina", my company was, first and mostly, a touring company. We never had a home in Quebec, we had a studio, but we did not have a theater. So we toured a lot, and we got to perform in some horrible places, but we got to perform in beautiful places, in places very interesting, very original. Theatre Cocoon, the National Theater of Catalonia in Barcelona, and there is a long list of fantastic new modern stages.

So after many years of touring when you decide to do your theater, you have references. Of course, you put all that together and we created this place called the Diamond. It's called the Diamond because a diamond has many facets, the programming is multi-faceted. Also, Quebec City is built on a cape called Cape Diamond because when the French discovered it, they saw sparkles. For a moment, they were illusions that it was full of diamonds, but it was very cheap rock. When I opened my first center, Bob (Robert) Wilson sent me a video message and he said a very Bob Wilson thing. He said, "For Robert Lepage, for his new center, our cities need centers, a diamond in an apple." I thought it was a very beautiful image that cultural centers are diamonds in a big apple because the idea that the apple is a big city, but a bigger kind of busy organized place, you have this thing where light goes through and where so anyways, that is the reason why.

One short word about the programming. I'm the Artistic Director of the center, so we program our plays, "Ex Machina" theater performances, but we also invite everything that is connected to theatricality. So we invite dance if the dance has some kind of theatricality, we invite certain forms of circus, small operas, we invite drag shows because it is very theatrical, when it's very theoretical. We also regularly have wrestling matches, which is the greatest theater form of all times, so it's a place about theatricality.

Takahagi: Up to now, we have spoken about the influence that Japanese culture has had on your work. Finally, I would like to discuss the topic of cultural appropriation I mentioned earlier. Although this perhaps isn't the appropriate time or place to go into details about it, I think it will be a rare and precious opportunity to directly discuss this topic with you. Let me briefly explain the background for those who are unfamiliar with it.

In June 2018, a work called SLÃV, which included black slave songs was performed three times at the Montreal Jazz Festival, and then protests were aggravated, and further performances were canceled. Of the six actors in the work, four were non-black. That matter precipitated the protests.

There is also the case of Kanata, a joint work between the Théâtre du Soleil and yourself, which took four years of preparation and was scheduled to be performed at the Théâtre du Soleil's home in Paris in December. However, when the performances were announced, large-scale demonstrations happened. The reason behind the demonstrators was that, among the multi-national actors of the Théâtre du Soleil, there were no members from the First Nations community of Canada on which the work was modeled.

Ariane Mnouchkine, director of Théâtre du Soleil, had considerable discussions, including opportunities for dialogues with artists from the First Nations communities in Canada. Ultimately it was announced in July that the Paris performances would be canceled.

Then in September, Mnouchkine staged Kanata - Episode I - La Controverse, which picked only the parts of the debate on the originally planned production. You participated in this production as a stage director with no compensation, and expressed your opinions on several occasions and in various forms about this matter. These issues are a little unfamiliar for us. Nevertheless, because it is a precious opportunity for us to be with you, I wonder if you could explain something about the background of these issues?

Lepage:

In five minutes? It's a giant, giant subject matter. But I will try to be brief.

Okay, so I will answer in two parts. The first part is that as a theater person, I believe that we should be allowed to borrow from other cultures, and that we have a duty to put ourselves in the skin of the other people. To better understand the other person, theater is made to put yourself in the place of another person. So the great tragedies of the Jewish diaspora, Anne Frank, a Japanese young actor should be allowed to play a Jewish, Holland girl to understand, to continue the memory of that. I think that that thing should never change, we should be allowed to play whoever we want. That's the first part of my answer.

So this being said, there are instances where, if I borrow from Japanese culture, French, German, those cultures and societies are very solid, rich, who had the chance to perform their own repertoire and talk about their own history, right? So that's one thing.

But if I borrow from the First Nation culture or from the black communities and their history, the black history, it's a different place because there's still struggle and often these people don't have the chance to tell their own stories. It's a difficult thing, in theater. We should be allowed to tell any story, but you have to navigate between that. One day, I heard a First Nation's person say, "Now they stole our children, they stole our territory and now they want to steal our tears." And that I went okay, that I think I understand, they have the impression they haven't told their story yet, so that's why I think we have to be very careful, we have to navigate and understand that, and that borrowing is a different thing than stealing. It took that crisis for me to understand the subtleness of that, when is it that you borrow and when is it that you steal.

Takahagi:

Thank you very much. I received some questions, and I would like to ask you only one of them.

Today, technology is progressing rapidly, with various new visual technologies being discovered, including 8K and the metaverse. You are said to be a visual magician, so could you share with us whether this technological progress has inspired you for new ideas of your own works in the future?

Lepage: I'm always interested in any new technology to see what it contains, how it can help better tell stories. But I'm not against it, but I think as long as theater is live and that is about communion, I don't have problems integrating new technology. In the 19th century, painting was the great way to talk about society and the grand masters and all that, and then photography arrives, and it does it faster, better, and more accurately. So painters wonder what is the use of becoming a painter now that photography is there, so for many years, they think painting is dead. But painting is not dead, painting is free now, because it doesn't have to do what photography does. It can become Cubist, it can become Dadaist, it can become Impressionist, it can become all of these extraordinary things. It never would have become like this if the technology of photography hadn't come in and imposed, so that's why I'm very open to any major big technological change because it probably will free my art. So if you are a good artist, it doesn't kill you, it makes you explore.

Takahagi: Thank you very much. I do hope that it will be possible to stage The Seven Streams of the River Ota once again in Japan. I also hope that you will maintain your interest in Japanese culture and that we can create something together in the future. Your works are being performed around the world and also continuously at Le Diamant in Canada. I would recommend our audience members today to go and see one of his productions when they have an opportunity. Thank you for coming today and for your kind attention. (applause)

A video of the dialogue can be found on the Japan Foundation's official YouTube channel.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=euUudcfqvZ0&t=1221s

October 21, 2022

Talk Session held at Tokyo Metropolitan Theatre

Co-organized by Tokyo Festival Executive Committee

Interpreter:TOKITA Yoko (GORCH BROTHERS Ltd.)

Photo: Sankei Kaikan

Related Events

Back Issues

- 2025.11.14 Stories from Both Si…

- 2025.10.24 Dialogue through Ani…

- 2025.6. 9 Creating a World Tog…

- 2024.10.25 My Life in Japan, Li…

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.5. 2 People-to-People Exc…

- 2024.5. 2 People-to-People Exc…

- 2023.12. 7 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2023.6.16 The 49th Japan Found…