Special Interview with Mr. Tanikawa Shuntaro

2020.3.23

【071: The 47th Japan Foundation Awards—the Bond between Japan and the World

Nurtured by Culture, Language and Knowledge】

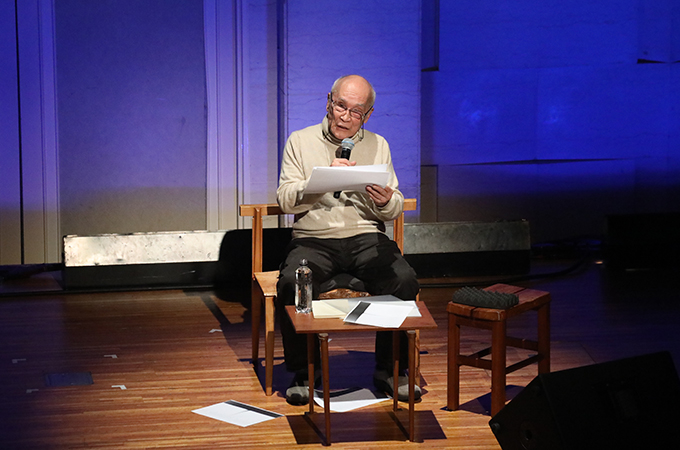

Mr. Tanikawa Shuntaro reading his poems

Composing poems for nearly 70 years, Mr. Tanikawa Shuntaro has created over 2,500 poems, excluding unpublished works. He continues to be one of the most beloved poets by his readers. Indeed, many people have read his poems over two or three generations. Using simple words, his clear and rhythmic poems are familiar to non-native learners of Japanese as well, and there are over 50 volumes of his poetry that have been translated into more than 20 languages, including English, Chinese, French and German.

On November 29, 2019, "Shuntaro Tanikawa Talk and Performance 'Mimi wo Sumasu'—An Evening of Talk, Poetry and Music" was held in commemoration of his receiving the Japan Foundation Award 2019. During the first part of the event, Mr. Tanikawa spoke with Ms. Ozaki Mariko, co-author of Shijin Nante Yobarete ("BEING CALLED A POET") about composing poems in the past, experiences with international exchange and more. In the second part, Mr. Tanikawa Kensaku, who is not only a composer, arranger and pianist but also Mr. Tanikawa's own son, gave a concert. There was also a collaboration between Kensaku's piano performance and his father's poetry reading. Many in the audience were moved to tears while listening to the readings of Listening, To Live and other masterpiece poems.

Afterwards, many expressed deeply emotional comments in a survey. They included: "I encountered Mr. Tanikawa's poems when I was in elementary school, and went through turning points in my life with his poems. I feel richer for having the opportunity to attend such a heart-warming event," "The well-coordinated performance between father and son was wonderful" and "For some reason, I couldn't stop crying, and my hardened heart was calmed."

In the following special interview, Mr. Tanikawa talks about the Japanese language, communication and composing poems.

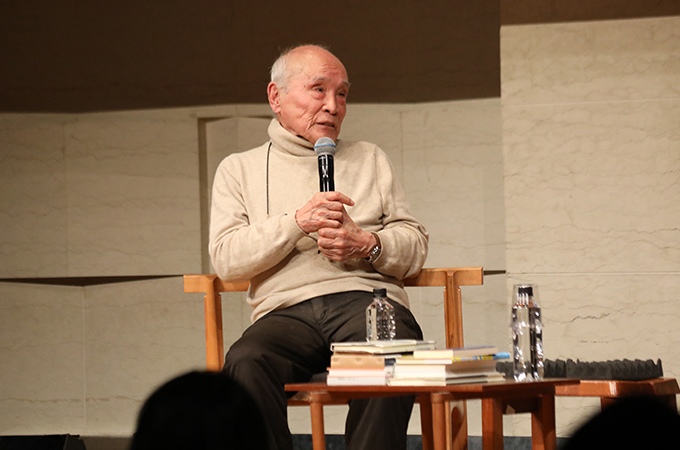

Mr. Tanikawa Shuntaro talking about memories of international exchange and the creative process

It's said that you have a deep understanding of the Japanese language equal to that of a linguist. You have also worked on translations of Mother Goose, the Peanuts series and more. How do you compare Japanese with other languages?

I don't know other languages the way I do Japanese, so it's difficult to compare, but for me, I think the sort of vague expressions in Japanese lend themselves well to poetry. For example, in English, you can't complete a sentence without inserting a subject. In Japanese, it is easy to write because you can complete a poem without a subject since you can sort of figure out who is speaking. But this means that I am often asked who exactly is speaking when my poems are translated, but I also don't really know who. I think English and French speakers hate this, but Japanese people easily accept it and think of it as a poem.

You extensively traveled the United States and Europe from 1966 to 1967. You have also had recitations and performances at the Japan Foundation events in Cologne, Berlin, Riga and Paris in 2003. With that abundance of experience abroad, could you tell us what impact has international exchange and multicultural interactions had on you?

When you go to places other than Japan, you find many rare things, be it food or scenery. I head off on trips with an interest in enjoying those rare things like other tourists. As for languages, I only speak Japanese, so I'm not able to directly engage in conversations with people from other countries. But reciting poetry is different from everyday conversation, and it's a kind of performance, so even if the listener doesn't understand the words, if the performance is interesting, then there will be plenty of fascinating things for the listener. People from all over the world play instruments, too. In this way, it is a fun experience to get on stage abroad with poets from other countries. There is a language barrier, to be sure, but I listen to the sounds of the words without caring much about the meaning.

It seems that it goes down well even with non-Japanese speakers when you recite your poem, Kappa (an imaginary creature in Japanese folklore), in Japanese. Has there been any influence on your creation from experiences gained from abroad or the fact that your poems have been translated into multiple languages?

I think it is probably influencing me more than I am aware.

I can't say for sure, but I think I am greatly influenced by reading the Japanese translations of poems by my favorite poets since I can't read them in their original language. I was influenced by Mr. Ogasawara Toyoki's translation of the poems of French poet Jacques Prévert. I'm influenced through the Japanese, you see. The same can be said for Shakespeare as well. I found the connection of the meaning and the way of telling the story interesting once it was put into Japanese through Mr. Yoshida Kenichi's translation, and I was influenced in the form of mimicking that style.

My generation was taught classical Chinese poetry from elementary school, so I think that influenced my style as well. The Chinese is quite rigid, completely different from the Japanese in The Tale of Genji. I copy this style from time to time in my own poems.

I think it is significant that the Japanese language uses Chinese characters, the hiragana and katakana scripts. I think it adds something.

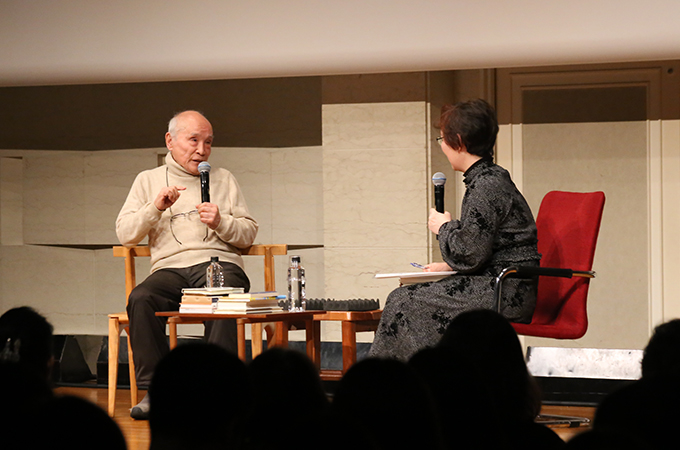

Mr. Tanikawa speaking with Ms. Ozaki Mariko and looking back over his nearly 70 years of work

On the other hand, you sometimes say that you can't trust words and that you may not be able to exactly put your feelings into words. It feels like with information coming and going in a faster pace we don't have the time to process it. How do you think language and communication with others ought to be?

Putting aside the words found in expressions, I think at least, that words spoken between two individuals is the most important thing. The words used change based on what kind of a connection the two individuals have. For example, if your partner is in a state where he or she can't speak with words, how do you communicate? Nowadays, people with disabilities are increasingly active in society, so we have to do our best in fostering communication with them. Besides, regardless of whether a person has a disability or not, communicating with somebody else is really difficult. Even between two native Japanese speakers, it's sometimes difficult to get your point across. For that reason, I think we need to be more careful with human linguistic communication skills. Japanese people tend to be nonchalant about this, comparatively speaking. At school, they teach us how to read and write, but there aren't many classes on speaking and listening. When I listen to questions and speeches given at the Diet, I think they are very poor at communicating. I think we ought to be mindful of the way we speak with Japanese.

Is there anything that you are careful about when speaking?

No, not at all (laughs)! My work involves writing, so I am careful when I write. But when it comes to speaking, I don't really pay much attention because I use my linguistic ability I have acquired naturally.

You have a wide circle of friends. Do you think you have a strong desire toward interacting with others like you describe in your collection of poetry, Two Billion Light Years of Solitude?

To be honest, I don't have a particularly strong desire to interact with others. I'm the kind of person who doesn't really need others, relatively speaking. As an only child, I enjoyed playing alone, and basically, being alone is when I feel most at ease. But at the same time, I do realize that is not desirable as a human (laughs). I am consciously making myself interact with other people because otherwise I know it's not quite right. If we get along, I'll open up and talk about serious stuff, but if we don't, I'll just shoot the breeze.

In modern-day society, it feels like information is coming and going in a faster pace and we don't have the time to process it. Do you think we've lost poetry (poems and poetic sentiments) and the act of taking the time to think?

I don't think we've lost poetry itself. Maybe. It's just a matter of whether we realize it or not, or whether we think it valuable or not. I think inherent poetry will always be with us.

When computer games and such things become popular, language without fail becomes fragmented. In its own light, it's a good thing, but I think some things get lost, too. For example, people have fewer chances to engage in long discussions or people become impatient when talking to someone who speaks slowly.

Language is basically a personal thing, so you have to realize it on your own, but don't you think the speed of conversation has increased in general? Listening to TV and radio, everyone talks so fast. Instead of listening to someone before talking, they all talk at the same time. It was slower paced in the past.

Piano and vocal performance by Mr. Tanikawa Kensaku

You incorporate the characteristics of the times in your poems.

Everything changes naturally. It's very fickle. In one way, it's good for a poet to be fickle.

Do you mean that you change like a chameleon?

Yes, and also it's good to be influenced by the times. Nowadays, you must do so or you can't make it, right?

You mean by incorporating new things?

That depends on what you are incorporating. Style is all that matters when writing. I believe having one's own, consistent style is a good thing, but the information and knowledge incorporated into the style changes incessantly. It is important in our line of work to figure out how to write and talk in one's style about these things.

You use a myriad of techniques for poems; it doesn't even seem like they were written by the same person. Do you still have any new things you'd like to try out?

I think it'll be difficult. I'm still capable of trying new things now, but I'll stop in the future. I think I'll get tired of it.

Regarding composing poems for nearly 70 years, you've said you don't like writing longhand and poems are easy because they're short. You also said you've continued writing poems because you get paid. Having consistently working for so many years, what aspects of poems do you find appealing?

Well, I don't like poems in the first place (laughs)! I didn't like poems at all when I was younger, and I never thought I'd become a poet. Once I entered the world of poetry, I felt it was very monotonous. I thought I could make it more interesting, and I changed myself along the way.

Also, everyone thought that it was okay with the situation where poets would be isolated, lose their connections with society and, to put it simply, be unable to earn money. I thought that poems can exist within society only when they earn money for their roles. I wanted poems to exist within society.

You are involved in picture books, plays, photographs, movies and a variety of other fields. You have a deep knowledge of music and are familiar with art.

Yes, but my preferences are very specific. I have an interest in movies, paintings and music. I can collaborate with things I like, but I have almost no interest in anything else.

Not limited to art, you absorb things from a variety of sources, including people around you.

For me, these people are "other." I get stimulation from them and it's very important for writing poems. After all, writing a poem isn't something you can do on your own.

Thunderous applause erupted from the audience for the well-coordinated father-son performance.

November 2019, Tokyo

Interview and Text: Terae Hitomi (Japan Foundation Communication Center)

Photography: Katano Tomohiro

Back Issues

- 2025.12.19 Echoes of a War Unli…

- 2025.6.24 Exclusive Interview:…

- 2025.5. 1 Ukrainian-Japanese I…

- 2024.11. 1 Placed together, we …

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.5. 2 People-to-People Exc…

- 2024.2.19 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2024.2.19 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2023.4.24 The 49th Japan Found…