The 51st (2024) Japan Foundation Awards Commemorative Event

Japanese Language Education in Mongolia and the History of the Association of Japanese Language Teachers of Mongolia

Aug 22, 2025

【Special Feature 084】

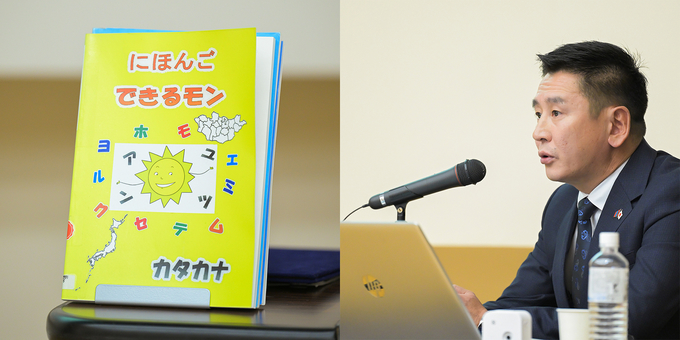

Japanese language education in Mongolia began in 1975 during the socialist era. Following the country's democratization in the 1990s, the number of Japanese language learners and teachers continued to grow steadily. In response to this development, the Association of Japanese Language Teachers of Mongolia was established in 1993 as a professional organization to bring together educators engaged in Japanese language education. In this commemorative lecture, Dr. Erdenebayar Batjargal, president of the Association and a key figure in the development and promotion of Japanese language education across Mongolia, looks back on this history. He discusses the current state of Japanese language education in Mongolia, the activities of the Association, and Nihongo Dekiru Mon, a textbook for primary and secondary education developed based on the JF Standard for Japanese-Language Education. Dr. Batjargal has made significant contributions over many years to advancing Japanese language education throughout Mongolia and fostering mutual understanding between Mongolia and Japan.

The lecture is also available for you to enjoy on the Japan Foundation's official YouTube channel.

Dr. Erdenebayar Batjargal, Association of Japanese Language Teachers of Mongolia

I would like to begin by expressing my sincere gratitude to everyone at the Japan Foundation for giving me the opportunity to deliver this commemorative address as a recipient of the Japan Foundation Awards. I would also like to thank all of you for taking the time out of your busy schedules to attend this event today. I hope that my talk will offer you some insights and be of value to your work or interests.

Earlier this morning, I had the pleasure of touring the Japan Foundation Japanese-Language Institute, Urawa, under the guidance of the deputy director. In fact, I myself took part in a training program at this very institute 24 years ago. It was truly a nostalgic and joyful experience to visit again after all these years. This time, I am accompanied by several fellow members of the Association of Japanese Language Teachers of Mongolia, who have traveled with me from Mongolia. Many of them have also received training at this very institute in the past, and as we toured the center today, they shared fond memories of their time here. I would like to extend my heartfelt thanks to the deputy director for guiding us through the visit.

Since we have this opportunity, I would like to briefly introduce the teachers who have accompanied me. First, we have Dr. Dolgor, one of the founding members and the former president of the Association of Japanese Language Teachers of Mongolia. Next is Ms. Purevsuren, vice president of the Association. We also have Ms. Enkhjargal, secretary general of the Association. Ms. Erdenetsetseg, head of the Japanese Language Department at the Mongolian-Japan Center for Human Resources Development. Representing primary and secondary education, we have Ms. Reiko Nakanishi from the Mongeni General School. And representing higher education, we are joined by Dr. Bayarmaa from the Mongolian National University of Education.

While it is the Association of Japanese Language Teachers of Mongolia that received this award, I truly believe it is a recognition of the collective achievements of all those involved in Japanese language education in Mongolia. It is an honor we proudly share. This award is a great source of encouragement for us, and we will continue striving to make further contributions to the field.

So, first of all, I would like to begin by briefly outlining the history and current state of Japanese language education in Mongolia. Following that, I will introduce the activities of the Association of Japanese Language Teachers of Mongolia as well as our development of the Japanese language textbook Nihongo Dekiru Mon, which is designed for primary and secondary education in Mongolia.

Japanese Language Education: Past and Present

Formal Japanese language education in Mongolia began in 1975, during the socialist era, at the National University of Mongolia, and it has since developed in response to various social changes. Based on those changes, the history of Japanese language education in Mongolia can be roughly divided into four periods.

The first period, from 1975 to 1990, was a time during which the foundation of Japanese language education was being established. The second period, from 1990 to 2000, saw Japanese being taught as a major subject at several universities in Mongolia. The third period, from 2000 to 2010, marked the peak of Japanese language education in the country. From 2010 onward, new developments have emerged, including the adoption of domestic and international foreign language education standards, which are gradually taking root.

Now, I would like to trace the history of Japanese language education in Mongolia through each of these periods. In March 1975, based on a resolution by the Higher Education Administration Bureau of Mongolia, Japanese language education was introduced as a minor subject for six third-year students majoring in Mongolian language and literature at the Faculty of Language and Literature at the National University of Mongolia. One of the instructors at that time was none other than Dr. Dolgor, the former chairperson of the Association of Japanese Language Teachers of Mongolia, who is with us here today. As we approach the 50th anniversary of Japanese language education in Mongolia, which began in 1975, we are standing at a significant milestone. From 1975 to 1989, Japanese was taught as a minor subject. Each year, approximately four students enrolled in the program, and during this period, a total of 58 students graduated with Japanese as their minor. Starting in 1988, interest in Japanese language education began to grow steadily, leading to the launch of an evening Japanese course at the Faculty of Foreign Languages, National University of Mongolia. What was notable about the students in these evening classes was their diverse professional backgrounds. Many were affiliated with various institutions, such as diplomatic services, media, construction, drafting, healthcare, and telecommunications.

In 1990, Mongolia transitioned from socialism to democracy and a market economy. This was also a time when exchanges between Mongolia and Japan entered a new phase. As bilateral relations and cooperation between our two countries deepened in many fields, the demand for Japanese interpreters, teachers, and speakers increased significantly, which led to the further promotion of Japanese language education. As a result, private universities began to be established alongside national universities, offering Japanese as a major field of study. Improvements in the education system and curriculum enabled both public and private institutions to offer Japanese language courses in various forms. New universities specializing in foreign languages were opened, including the establishment of the Department of Japanese Studies within the School of International Relations at the National University of Mongolia in 1990. In addition, Japanese language programs began to be offered at several private universities. Ulaanbaatar University introduced Japanese language education in 1992, followed by Ireedui University in 1993, and Tsog University and the University of Language and Civilization in 1994. Starting in 1996, Japanese language courses were also launched at the Mongolian University of Science and Technology, the University of Culture and Education, Seruuleg University, Otgontenger University, Orkhon University, Oyu University, and Onol University. Japanese language education expanded not only within the capital city of Ulaanbaatar but also to regional areas (for example, Khovd University in the western region and Margad Institute in Darkhan). In addition to higher education institutions, Japanese language instruction was introduced at the primary and secondary level as well. Public schools, such as the Mongeni School, began offering Japanese language education. Private institutions also began offering Japanese language education. Outside of formal educational institutions, several Japanese language centers--such as Nahiya, Gerel, BASE, and the Choi Center--also established beginner- and intermediate-level Japanese courses.

The expansion and development of Japanese language education in Mongolia would not have been possible without the invaluable support of the Japan Foundation. The Japan Foundation has played an essential role in promoting Japanese language education in Mongolia by supporting teacher-training programs and providing teaching materials. Thanks to their continued efforts, Japanese language education has reached its current state. In 1992, the first volunteers specializing in Japanese language instruction from the Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteers program were dispatched to Mongolia. As mentioned earlier, one of the key reasons for the expansion of Japanese language education in Mongolia lies in the foundation laid by the students who studied Japanese as a minor subject between 1975 and 1989. In other words, during the socialist era, the training of Japanese language teachers was already underway. To put it another way, most of the 58 individuals who graduated from the Japanese minor program in the Mongolian Language Department--later incorporated into the Department of Foreign Languages--at the National University of Mongolia went on to become Japanese language teachers.

The period from 2000 to 2010 is often regarded as the peak of Japanese language education in Mongolia. In fact, Mongolia was once ranked first in Asia for the number of Japanese language learners, when compared proportionally to population size. As I mentioned in my remarks at yesterday's award ceremony, there are now a significant number of educational institutions involved in Japanese language education at the primary, secondary, and tertiary levels in Mongolia. According to the 2021 Survey on Japanese-Language Education Abroad, conducted by the Japan Foundation, there were approximately 360 members in the Association of Japanese Language Teachers of Mongolia. This number may seem modest compared to that of larger countries in terms of population ratio. However, it represents a remarkably high figure for Mongolia. One of the defining features of this period was the strengthening of the foundation of Japanese language education. In addition, most universities began to offer master's and doctoral programs in the field. In 2002, the Mongolian-Japan Center for Human Resources Development was established with the aim of fostering individuals who could contribute to the development of Mongolia's market economy and enhancing mutual understanding between Mongolia and Japan. Japanese language courses were offered as part of this initiative, playing a significant role in the further promotion of Japanese language education. At the same time, nongovernment institutions also began to offer Japanese language courses. At one point, as many as 70 courses were being held. Beyond the formal school system, the number of Japanese language courses continued to increase, and around 20 different institutions were actively teaching Japanese. In regional areas as well, Japanese language education expanded to secondary and primary institutions. For instance, in cities and provinces such as Darkhan, Erdenet, Khovd, Uvurkhangai, Bayankhongor, Tuv, and Baganuur District, Japanese language programs were launched in primary and secondary schools.

On the political front, the establishment of the Japan-Mongolia Comprehensive Partnership in 1996 and the strengthening of the Strategic Partnership in 2010 further deepened bilateral relations. As a result, people-to-people exchanges between Mongolia and Japan flourished, creating an even more favorable environment for Japanese language education. With the increase in both institutions and learners, the need for evaluating Japanese language proficiency became more apparent. In response, the Japanese-Language Proficiency Test (JLPT) began to be administered in Mongolia in 2000. Furthermore, the Examination for Japanese University Admission for International Students (EJU) was introduced in 2003. A new direction in foreign language education in Mongolia also emerged. In 2005, the Ministry of Education of Mongolia issued a national foreign language education standard. This development had a significant positive impact on the expansion of Japanese language education across the country.

Through Japanese language education, interest in various aspects of Japanese traditional culture and subculture has grown among Mongolian learners. These include origami, the abacus (soroban), kendama, kendo, karate, ikebana, as well as anime, manga, and cosplay. In addition, study tours to Japan by teachers and students from primary and secondary institutions along with programs such as the JENESYS exchange initiative, which began in 2007 to promote mutual understanding with Japan, have played a significant role in deepening learners' understanding of Japan and have served as a strong motivation for studying the Japanese language.

Regional exchanges between Mongolia and Japan have also developed. For example, Tottori Prefecture and Mongolian central province have established a sister-prefecture relationship, and Ulaanbaatar and Miyakonojo City in Miyazaki Prefecture have become sister cities. Such regional partnerships have contributed to a growing interest in Japan and the Japanese language, leading to an increase in the number of learners. A variety of Japanese language textbooks and dictionaries have been developed specifically for Mongolian learners. Graduates of Japanese translation and interpretation programs have also translated numerous works of Japanese literature and novels into Mongolian. During the socialist era, a wide range of literature was translated into Mongolian from various foreign languages. However in more recent years, a significant number of literary works have been translated specifically from Japanese.

This widespread interest in the Japanese language has been supported by important changes in Mongolia's foreign language education policy. During the socialist era, foreign language education was limited primarily to Russian. With the shift to a more open education system, English and other languages have become part of the curriculum. As part of the reform and enhancement of foreign language education in Mongolia, the Ministry of Culture and Education, related government agencies, and universities specializing in foreign languages have held a series of academic conferences. These include discussions on national language education policy, academic forums on foreign language education in Mongolia, conferences on globalization and national language policy, assessments of the current state of foreign language education in Mongolia, and symposia on teaching content and methodology at Mongolian universities.

Amid these developments, Japanese language education in Mongolia has increasingly drawn attention. Teachers involved in Japanese language education, as well as scholars conducting research in the field, have actively participated in these initiatives and have contributed significantly to the promotion and advancement of Japanese language education.

While responding to domestic educational demands and expectations, attention was also paid to international developments in foreign language education. In 2011, two major international standards--the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) and the U.S.-based Standards for Foreign Language Learning in the 21st Century--were translated into Mongolian. Efforts were made to study and adopt these standards and to explore their implementation across various foreign language programs in Mongolia. In line with this, the Association of Japanese Language Teachers of Mongolia translated the JF Standard for Japanese-Language Education, which was introduced by the Japan Foundation in 2010, into Mongolian in 2011. We worked actively to incorporate this standard into Japanese language education in Mongolia.

As a result of these efforts, a new approach to Japanese language education has begun to take shape in the country. There has been a noticeable improvement in the academic depth and quality of instruction, particularly within higher education institutions, where Japanese language education has become increasingly specialized. Meanwhile, institutions such as the National University of Mongolia, the University of the Humanities, and the University of Culture and Arts have seen a steady increase in the number of students choosing Japanese language as a minor across various academic fields. As mentioned earlier, since the 2010s, workshops have been held in primary and secondary education to promote a unified standard. Pilot versions of standardized textbooks have been developed, and regular training seminars have been organized for Japanese language teachers.

Around 2012, the structure of Japanese language education institutions in Mongolia began to shift. First, we began to observe a decline in the number of Japanese language learners as well as in the number of institutions offering Japanese language education. One recent factor contributing to the decrease in Japanese language education at the primary and secondary levels is the shift in the foreign language education system--particularly the changes introduced at the elementary school level. Japanese is now being taught as part of the elementary school curriculum, which has, somewhat counterintuitively, led to a slight decline in the number of Japanese learners in these grades.

Another factor is the growing emphasis on balancing mother-tongue education with foreign language education. Additionally, we are seeing a rise in the number of learners who study Japanese for specific purposes, which also affects the overall trends. For example, a new initiative was established under the KOSEN Project--a technical college study program jointly developed by the governments of Mongolia and Japan. Another major factor is the increase in technical-intern trainees. With the growing number of Mongolian technical trainees, more institutions have begun offering Japanese language courses to meet this demand.

Now, I would like to move on to the next slide, which illustrates the changes in the number of Japanese language institutions, learners, and teachers in Mongolia. The blue bars represent primary and secondary education institutions, pink indicates higher education institutions, and purple shows institutions outside the formal school system. This chart shows the number of learners, and here, we have the number of Japanese language teachers in Mongolia. As I mentioned earlier, the figures may appear relatively small at first glance. However, considering that Mongolia's population is only about 3.5 million--which is roughly equivalent to the number of people who pass through Shinjuku Station in a single day--the ratio of Japanese language teachers and learners to the total population is actually quite significant. In fact, from a population-proportional standpoint, Mongolia ranks quite high among Asian countries. This chart shows the number of Japanese language education institutions in Mongolia. In recent years, the most notable increase has been among institutions that provide language training for technical-intern trainees. This system has expanded rapidly, and the number of institutions offering Japanese language education has risen significantly. This has contributed to the overall growth in the number of Japanese language education institutions in Mongolia.

That concludes my brief overview of Japanese language education in Mongolia.

Efforts of the Association of Japanese Language Teachers of Mongolia

Now, I would like to turn to the activities of the Association of Japanese Language Teachers of Mongolia. There will be time for questions and discussion later in the program. We are joined today by many distinguished guests, including Dr. Dolgor, the former president, who is often referred to as "the mother of Japanese language education in Mongolia," amongst other members. So please feel free to direct your questions to any of us during the Q&A session.

The Association of Japanese Language Teachers of Mongolia began its activities in 1993, starting with small-scale study groups. These meetings focused on developing university curricula, course content, and teaching materials. From 1995 onward, we began to see a noticeable increase in the number of Japanese language learners and institutions offering Japanese language programs at the primary and secondary levels in Mongolia. As new challenges emerged, we started to hold discussions to address these issues. With the growing number of Japanese language education institutions across the country, it became clear that we needed an organization to bring together the teachers from these various institutions. What began as a small study group gradually expanded and led to the official establishment of the Association of Japanese Language Teachers of Mongolia. From that point on, we began full-scale support and coordination of Japanese language education activities throughout the country. Our aim has been to promote the broad development and dissemination of education in Mongolia by strengthening the professional skills of Japanese language teachers and fostering highly capable Japanese-speaking professionals. In addition, we have contributed to the promotion of mutual international understanding through cultural exchange and close collaboration with Japanese language institutions and educators.

As the Association of Japanese Language Teachers of Mongolia has grown, so too have its institutions and membership. According to the 2021 Survey on Japanese Language Education Abroad conducted by the Japan Foundation, the Association of Japanese Language Teachers of Mongolia had the following institutional presence: 28 primary and secondary institutions offering Japanese language education, 24 higher education institutions (universities), and 66 private Japanese language schools and courses. All educators engaged in Japanese language teaching at these institutions are members of our Association. At the time of the Survey, our total membership stood at approximately 360 teachers. Recently, there has been a particularly noticeable increase in the number of private Japanese language schools and learners. The Japanese Language Education Abroad will release an updated edition of the Survey based on 2024 data. The results are expected to be published around November of the following year [2025] and are likely to reflect changes in these numbers.

Now, I would like to introduce the annual activities of the Association of Japanese Language Teachers of Mongolia. Our annual activities include the Japanese Language Education Symposium, Inter-School Japanese Speech Contest, Kanji Naadam, and a kanji-quiz competition. The Association supports research through Japanese language education study groups, issues calls for research papers, and publishes the Mongolian Journal of Japanese Language Education. It also conducts study sessions for primary and secondary Japanese language education institutions and provides support for courses on Japanese language, language education, and teaching methodology. Furthermore, the Association administers the Japanese-Language Proficiency Test (JLPT), provides support for the Private Study Abroad Examination, conducts Surveys on Japanese Language Education Institutions, and organizes the National Japanese Language and Culture Conference. Additionally, it is involved in the development of teaching materials for primary and secondary Japanese language education institutions, among other activities.

These are the major activities carried out by the Association of Japanese Language Teachers of Mongolia throughout the year. We continue to pursue these efforts with dedication, and we were deeply honored to have these activities recognized with the Japan Foundation Awards, presented just yesterday.

Now, I would like to introduce each of the activities of the Association of Japanese Language Teachers of Mongolia that I mentioned earlier. First, let me begin with the Japanese Language Education Symposium. This symposium was launched with the generous support of a grant from the Japan Foundation. The main purpose of the symposium is to foster the professional growth of Japanese language teachers by sharing the outcomes of their research and teaching practices. It also provides a platform to address various challenges in Japanese language education in Mongolia and to acquire new insights and knowledge. The first symposium was held in 2007, and since then it has been conducted annually. Even during the COVID-19 pandemic, the symposium was held online, allowing us to maintain continuity. This year marks the 16th edition of the symposium. The symposium features keynote lectures, presentations, workshops, breakout sessions, and panel discussions and is made even more meaningful by the participation of highly experienced and knowledgeable guest speakers from Japan and other countries. One of our most memorable keynote speakers is Professor Shimada, who has become affectionately known in Mongolia as "Shimada-sensei of Japanese." Many Mongolians studying Japanese know his name, and we are honored that Professor Shimada is with us here today. Following the symposium, we also hold a networking reception. It provides a valuable opportunity for participants to freely exchange ideas with the guest lecturers and with one another. These gatherings are highly appreciated as they allow for informal and enriching discussions. We also conduct a survey of all participants and stakeholders after each symposium, and we carefully reflect their feedback in the planning of the next event. Additionally, a symposium report is compiled and distributed to all participants and related parties.

Next, I would like to speak about the Japanese speech contest. The Inter-School Japanese Speech Contest is also held with the generous support of the Japan Foundation. It was first launched in 1995, and this year marks its 30th anniversary. Once we return home, we will immediately begin preparations for the initial selection process. The speech contest itself is scheduled to take place in November. This 30th contest will be co-hosted by the Embassy of Japan in Mongolia, the Association of Japanese Language Teachers of Mongolia, the Mongolian-Japan Center for Human Resources Development, and the Faculty of Foreign Languages at the Mongolian University of Science and Technology. It is also sponsored by the Association of Mongolians in Japan NPO and the Japanese Business Council in Mongolia NGO. The contest is divided into two divisions--one for high school students and one for university students. Originally, the contest was conducted on an individual basis and was open to participants from across the country. However in 2015, in response to a request from the then-ambassador extraordinary and plenipotentiary of Japan to Mongolia, who hoped to see more schools participate, the format was changed to an inter-school competition. The judging process involves several stages. First, participants submit their written speeches. Then, judges conduct the first and second rounds of evaluation. Finally, selected participants advance to the final round. Ten finalists are selected for each division--high school and university--and the top winners are awarded a place in the JENESYS Program, an exchange initiative to visit Japan. This contest provides an excellent opportunity for Japanese language learners to express their own ideas in Japanese, using the language skills they have worked so hard to acquire.

Next, I would like to introduce the Kanji Naadam, a kanji-quiz competition. The word naadam in Mongolian means a competitive event or tournament. This particular competition, focused on kanji, was initiated in 2016, following a proposal from teachers at primary and secondary Japanese language institutions. The Kanji Naadam is supported by the Association of Japanese Language Teachers of Mongolia and is held once a year, targeting middle and high school students from primary and secondary institutions offering Japanese language education. This year marks the 8th edition of the event, and both the number of participating schools and students have been steadily increasing each year. The competition was launched with the aim of helping non-kanji-background learners discover the fun and fascination of kanji. Each participating school sends five middle school students and five high school students, and the event involves various kanji-themed games and activities that allow students to enjoy kanji through play. The event is planned and operated by teachers from member institutions of the Association, with support from many volunteers. Thanks to this collaborative effort, the event has continued to thrive. Working together on the planning and execution of the event has also deepened mutual understanding among teachers and has highlighted the importance of collaboration and teamwork.

Moving on, the Japanese Language Education Research Group functions under the umbrella of the Association of Japanese Language Teachers of Mongolia. This group was established in 2007, and to this day, it holds monthly meetings, with the most recent session in the past month marking its 124th gathering. The goal of this group is to provide an open platform where teachers and graduate students can share their research findings or practical teaching experiences in a relaxed and informal setting. It also serves as a valuable opportunity for participants to learn from one another and exchange ideas. Through these regular meetings, individual teachers are able to enhance their knowledge and professional expertise, while also strengthening their networks with fellow educators. Each meeting usually consists of one or two presentations, followed by group discussions. The topics covered are diverse. For example, last year's sessions included presentations on ongoing research, as well as analyses using corpus linguistics--a technique learned at one of our symposia. We also featured reports from teachers who had participated in the Japan Foundation training programs, which offered new inspiration to many attendees.

Finally, we publish the Mongolian Journal of Japanese Language Education every two years (since 2013). This publication features research papers by teachers from primary and secondary schools involved in Japanese language education, as well as by graduate students in master's and doctoral programs specializing in Japanese studies.

The study group functions as a community platform for teachers from primary and secondary Japanese language institutions affiliated with the Association of Japanese Language Teachers of Mongolia. It has been officially recognized by the Ulaanbaatar City Education Department and has been held regularly for nearly 20 years. Meetings are conducted once a week at the Teachers' Association office, and the group engages in many activities. It includes discussing challenges in the use of teaching materials, sharing questions and perspectives on Japanese culture, exchanging ideas on teaching methodologies, sharing information on teaching resources, receiving advice from experienced teachers, conducting model lessons and lesson planning, disseminating information externally, and planning and managing projects related to primary and secondary education within the Association.

Next, let me introduce our support for Japanese language, Japanese language education, and teaching methodology courses. One notable initiative is the MAEDA SAN Support Project, which provides assistance for retraining young Japanese language teachers and supporting students majoring in Japanese language education. What makes MAEDA SAN especially remarkable is that it is not a group-based project, but rather a private support effort led by an individual.

The Association of Japanese Language Teachers of Mongolia also serves as a co-organizer of the National Japanese Language and Culture Competition, hosted by the National University of Mongolia. This is a relatively new initiative that began in 2022, targeting Japanese language learners from universities across the country. The competition is scheduled to be held every three years. Participants compete based on their scores in a written test and a quiz, making it not only an opportunity to deepen their knowledge of Japanese language and culture but also a chance to demonstrate and develop teamwork skills. We believe it is a truly innovative and enriching activity for students.

Next, I would like to talk about the Japanese-Language Proficiency Test (JLPT), which is organized by the Japan Foundation. In Mongolia, the JLPT has been administered by the Association of Japanese Language Teachers of Mongolia since 2000. Initially, the exam was held once a year only in the capital, Ulaanbaatar. However, since 2019, it has been held twice a year. As the number of Japanese language learners in regional areas has increased, the exam is now also conducted outside of the capital. In 2014, the test began to be held once a year in Arvaikheer, Uvurkhangai Province, and in 2022, an annual session was added in Darkhan as well. This local implementation has significantly reduced the burden for examinees in regional areas who previously had to travel long distances. This chart shows the number of JLPT applicants in Mongolia. As you can see, 2019 marked a peak in the number of learners and marked the largest number of applicants due to the introduction of the twice-yearly test schedule, which led to a sharp rise in participation. However in 2020, there was a significant decline due to the impact of COVID-19. Currently, as of fiscal year 2024, the number of JLPT applicants has once again exceeded 2,500, as I mentioned earlier.

The Examination for Japanese University Admission for International Students (EJU), administered twice a year in Japan and overseas by the Japan Student Services Organization (JASSO), has also been conducted in Mongolia since 2002, with the Association of Japanese Language Teachers of Mongolia serving as a cooperating institution.

In addition, the Association has entered into a commissioned contract with the Japan Foundation, through which we undertake survey work on the status of Japanese language education in Mongolia. By referring to the Survey on Japanese Language Education Abroad, published by the Japan Foundation, you can gain a comprehensive understanding of the state of Japanese language education in Mongolia.

Since 2001, prompted by the introduction of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR), research on foreign language education standards has grown in Mongolia. In response, the Association of Japanese Language Teachers of Mongolia launched a project to introduce the JF Standard for Japanese-Language Education in Mongolia. Another major initiative of the Association of Japanese Language Teachers of Mongolia has been the development of Japanese language teaching materials for primary and secondary institutions, guided by the JF Standard for Japanese-Language Education.

Nihongo Dekiru Mon: The Japanese Textbook Tailored for Mongolian Primary and Secondary Schools

Next, I would like to speak about the textbooks used in Japanese language education. Several of the teachers who were directly involved in the development of these teaching materials are present in the audience today. If you have any questions regarding textbook development, we would be happy to address them during the Q&A session later.

In the past, a variety of textbooks were used in Mongolia, including Wakuwaku Nihongo (Japanese for beginners), Minna no Nihongo, Hiroko-san no Tanoshii Nihongo, and Dekiru yo. At present, Minna no Nihongo, Dekiru Nihongo, and Nihongo Dekiru Mon are still commonly used across primary and secondary Japanese language education institutions. Even after democratization, the legacy of the socialist-era education system remained in place, and many teachers were accustomed to those traditional teaching styles. As a result, in beginner-level Japanese classes, the emphasis tended to be on grammar-based instruction, focusing more on memorizing what the teacher said, rather than encouraging students to think and express themselves in their own words. In other words, the teaching approach was knowledge transmission-oriented.

Before the development of Nihongo Dekiru Mon, the situation was quite different. In the field of Japanese language education, there were no official national curriculum guidelines issued by the government. As a result, primary and secondary institutions offering Japanese language education lacked a standardized syllabus, and there was no formal network among teachers. This also meant that teachers had few opportunities for mutual learning or professional development. One of the major challenges at the time was the lack of level-appropriate textbooks, especially for young learners. In response to this situation, Dr. Dolgor--then president of the Association of Japanese Language Teachers of Mongolia and a professor at the National University of Mongolia--took the initiative to launch Mongolia's first textbook-development project specifically for primary and secondary education. The textbook was structured into four parts: Part 1 focused on teaching hiragana and katakana, parts 2 and 3 covered grammar and conversation, and part 4 emphasized reading comprehension and kanji. At the time, the number of Japanese language learners in Mongolia was steadily increasing, particularly at the primary and secondary education levels, where the growth was especially remarkable. However, many Mongolian Japanese language teachers were not yet familiar with key concepts such as the CEFR or the JF Standard, and foreign language education standards in general were not widely recognized in Mongolia. To address this, we translated the Japanese language summary of the 2010 JF Standard into Mongolian and distributed it to Japanese language institutions, including the Ulaanbaatar City Education Department. In 2011, study sessions on the JF Standard officially began in Mongolia, and teachers from primary and secondary institutions started meeting regularly to learn and exchange ideas. As part of this initiative, two pilot schools--including Mongeni School, located in Ulaanbaatar, and Mergedu School in Uvurkhangai Province--were designated to implement JF Standard-based lessons. At that time, Mongeni School had around 120 Japanese language learners. Meanwhile, Mergedu School, located about 430 kilometers from Ulaanbaatar in a rural area with a population of just over 100,000, had an impressive 350 Japanese language learners. Because of the school's remote location, many people made the effort to travel to Mergedu School to support and observe the implementation of JF Standard-based lessons.

Let me share a brief example. This is an excerpt from an interaction between a teacher and students conducted in Japanese. On this occasion, Ms. Reiko Nakanishi, who is with us here today, asked her students in Japanese, "What did you eat for breakfast?" All of the children answered "airag." For those who may not be familiar the word, airag is a traditional Mongolian beverage made from fermented mare's milk--also known as kumis. It's important to note that this is not an alcoholic beverage in this context-- the children are not drinking alcohol. Airag is widely regarded as a traditional and culturally common beverage in Mongolia, including among children.

Starting in 2012, regular JF Standard study sessions were launched at the Mongolian-Japan Center for Human Resources Development. Under the guidance of Mr. Junji Katagiri, who was dispatched to the Japan Center at the time, these sessions extended beyond just the pilot schools and came to include teachers from 20 primary and secondary institutions offering Japanese language education.

Soon after, a large-scale textbook-development project began to create teaching materials aligned with the JF Standard. Schools participating in this project accounted for about 60 percent of all primary and secondary Japanese language education institutions in Mongolia. Since the launch of this expanded project, 14 schools have contributed to the development of the textbook, and 24 teachers have been involved in the writing and editing process. When the textbook was first completed, it was adopted and used in the classroom by 10 schools. As of now, the number of schools actually using the textbook in class has grown to approximately 20 schools.

In 2013, to deepen our understanding of the JF Standard, we invited three distinguished speakers to deliver keynote lectures at that year's Japanese Language Education Symposium: Dr. Kazuko Shimada from the Akuras Japanese Language Institute, Dr. Jung Ki-Young from Busan University of Foreign Studies, and Dr. Eldonbator from Inner Mongolia University. As per our request, we were fortunate to gain insights into the current state of standard-based education in each of their countries.

Through these various efforts, the textbook Nihongo Dekiru Mon was developed. Some of you may have already seen it. It is currently also being exhibited in the library of the Japan Foundation Japanese-Language Institute, Urawa, where we are today. Please do take a moment to have a look if you haven't already. What you see here is the katakana volume of the textbook. One key feature of this textbook is that it does not follow the traditional "a-i-u-e-o" sequence for teaching kana. Instead, it begins with practical and familiar words for the learners--words they are likely to use in daily life. For example, students first learn to read and write their own names, as well as words like Mongolia and Ulaanbaatar. That means the textbook may start with the character mo instead of a, which reflects a more practical, learner-centered approach. This decision was made through active discussion among teachers, focusing on what would be most relevant and engaging for their students. Another important feature is the incorporation of Can-Do* statements, in line with the JF Standard. This allows students to create learning portfolios, in which they can collect and reflect on their classroom work and track their own progress.

- *Can-Do: A statement framed as "can do" that describes specific language skills or tasks a learner is able to perform at a particular stage of proficiency. These statements are categorized according to the CEFR language-proficiency levels.

One more significant aspect of this JF-aligned textbook is that it comes with a teacher's guide written specifically for Mongolian teachers. This guide clearly explains effective instructional methods. Finally, while many traditional Japanese language textbooks were written exclusively in Japanese, Nihongo Dekiru Mon includes Mongolian explanations alongside the Japanese content. This bilingual structure allows learners to better understand lesson objectives, questions, and activities, which has made the textbook significantly more accessible and useful for students.

In 2024, we marked the 10th anniversary of the development of Nihongo Dekiru Mon. To gain a clearer understanding of its current use and effectiveness, we conducted a belief survey. The survey targeted Japanese language teachers who actually use the textbook, their students, and also their parents or guardians. The survey revealed a number of advantages and disadvantages associated with using Nihongo Dekiru Mon. From the teachers' perspective, some of the key advantages included a shift away from traditional grammar-focused instruction, an increase in student-to-student interaction and classroom communication, and the realization that with some creativity and flexibility, they could make the lessons more engaging and enjoyable. This created a noticeable change in their own mindset toward how Japanese should be taught. However, teachers also noted several challenges, such as too few kanji covered in the textbook, leading to concerns about preparation for the JLPT, as well as a lack of supplementary materials, which means teachers must create them on their own time. From the learners' side, the reported advantages included the presence of illustrations, which made lessons easier to understand, explanations in Mongolian, helping them know exactly what they were learning each day, and bilingual vocabulary support, which made memorization easier. Lessons were also personally relevant and practical, which students found very motivating. This learner-centered, relatable content was clearly well received. Among the disadvantages, students echoed teachers' concerns, especially the limited coverage of kanji. Some also commented that certain topics included in the textbook touched on personal or sensitive matters--making them reluctant to engage or respond in class. From the parents' perspective, one major advantage was the inclusion of Mongolian-language explanations. This allowed them to understand what their children were learning in class and, more importantly, to engage with their children about their studies at home. However, some parents also pointed out disadvantages, such as the limited number of kanji included in the textbook, which raised concerns about preparation for the JLPT, the price of the textbook, which some felt was a bit high, plus the lack of a dedicated workbook, which made it difficult for both students and parents to understand what homework was assigned.

These findings emerged clearly from the belief survey, and we at the Teachers' Association are taking them seriously as key issues to address in the future revision process. As shown through this survey, we have identified several important challenges and areas for improvement as we prepare for the next edition of the textbook. Moving forward, teachers at primary and secondary institutions will continue to engage in study groups and collaborative efforts to guide this revision process.

We recognize the growing importance of responding to a new era with AI integration and data privacy in education and knowledge transfer to new and younger teachers. We are now entering a new phase where we will listen closely to the voices of the teachers using the textbook, and together rebuild a version that meets the needs of today's learners and teachers alike. The primary and secondary Japanese language textbook Nihongo Dekiru Mon has developed through the efforts and aspirations of many teachers and educators across Mongolia. It is currently being used in classrooms nationwide and reflects both the realities and hopes of those who created it. At the Association of Japanese Language Teachers of Mongolia, we remain committed to supporting and improving this textbook, so that it may continue to serve as a valuable resource for Japanese language education in Mongolia. A list of references can be found here.

Thank you all very much for your attention.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

【Q&A Session】

Q: Were the Can-Do statements in the textbook Nihongo Dekiru Mon included in the JF Standard for Japanese-Language Education? Or were they created originally by the Association?

A: Dr. Erdenebayar Batjargal: Indeed, some of the Can-Do statements used in the textbook were carried over from existing frameworks. However, many others were newly created by the teachers themselves. Through numerous study-group discussions, teachers at primary and secondary institutions came together, shared their experiences, and developed Can-Do statements based on actual classroom realities and learner needs. So while some elements may be similar to existing standards, many of them were reconsidered and redesigned by the teachers themselves, specifically for the Mongolian context.

Ms. Nakanishi: Hello, my name is Nakanishi, and I have been involved in primary and secondary Japanese language education in Mongolia for over 30 years. Thank you all for being here today. In response to your question, when developing the Can-Do statements, teachers selected topics that were familiar and relevant to their own students. They gathered these themes and built the Can-Do items around them.

Q: What was the most important thing you were careful about while creating the textbook Nihongo Dekiru Mon?

A: Ms. Nakanishi: One of the most difficult issues we encountered was related to the topic of family. As you know, in Mongolia--and this may be the case in many parts of the world--not all children live with both parents. Some come from single-parent households or have other unique family situations. This raised a fundamental question for us: What does "family" mean in today's society? We realized that the traditional idea of a family consisting of both parents was not something that could be easily accepted or assumed in every classroom, yet teaching these fundamental topics remains essential. That's when many discussions took place. One idea that emerged was to use references from anime, such as Nobita's father from Doraemon, as a way to introduce the idea.

Dr. Erdenebayar Batjargal: This again ties into what we saw in the belief-survey results from both teachers and students. Unless we conduct thorough research beforehand, there is a risk of including topics in textbooks that some children may feel uncomfortable being asked about or may prefer not to discuss at all. If such sensitive content ends up in the textbook, it can cause emotional distress for students in the classroom. That is why we firmly believe that careful, evidence-based development is crucial in creating truly effective and empathetic educational materials.

I also heard, in later discussions, that teachers struggled greatly with the question of how many kanji to include in the textbook. They were very aware that if they included too many kanji, young learners might quickly become overwhelmed or lose interest. So the decision was made to limit the number of kanji, keeping the lessons more accessible and engaging. However, as we've seen from the feedback, that very decision has now been pointed out as a disadvantage.

Looking back, we now realize that if we had included a greater number of kanji, it might have helped address some of the concerns that have since been raised. In Mongolia, many parents strongly encourage their children to take the Japanese-Language Proficiency Test (JLPT) as a way to assess their Japanese skills objectively. As a result, parents tend to place great importance on their children's JLPT results. Therefore, when designing a textbook, we must also consider how well it supports learners in preparing for standardized assessments, such as the JLPT.

The question of how many kanji to include must be considered very carefully. If not handled properly, it could again lead to similar drawbacks or negative feedback. That is why we are now taking active steps toward improving and revising Nihongo Dekiru Mon. We are committed to addressing these issues to ensure that future versions of the textbook will be even more effective.

Q: In Mongolia's primary education, is there an opportunity to learn foreign languages other than Japanese? What is the purpose of Japanese language education?

A: Dr. Erdenebayar Batjargal: In Mongolian elementary schools, students study not only Japanese, but also a variety of foreign languages, including English and others. During the socialist era, the only foreign language we had access to as a second language was Russian. However, after Mongolia transitioned to a democratic system in the early 1990s, students were given the opportunity to choose from a wider range of foreign languages. Since around 1990, English has become available as an elective, followed by Japanese, Chinese, Korean, and others. There was a particular period that I referred to earlier as the peak of Japanese language education, when the number of Japanese learners in primary and secondary schools grew rapidly. The growth was so significant that even we, as educators, were surprised by the large number of students choosing to learn Japanese. Since students are now free to choose the foreign language they wish to study, they are more likely to select one based on personal interest or preference.

Dr. Dolgor: As for why children in Mongolia begin studying Japanese, the reasons vary greatly depending on each family's situation. Sumo wrestling is one such influence. Some parents are deeply interested in sumo and want to learn more about it through their children. By having their children learn Japanese, they hope to gain a better understanding of the sport and its cultural background. Food is another clear example, as seen in dishes such as sashimi or tonkatsu, which we also call tonkatsu in Mongolian. Since many adults don't have time to study Japanese themselves, they often encourage their children to learn it, hoping to connect with Japan through their children's language studies.

When I was younger, only one or two students per year aimed to become academic researchers or planning fellows, but since the 1990s, that number has increased rapidly. In fact, many parents had the mindset that if they had four children, at least one should study Japanese. More recently, children themselves have started expressing interest in Japan--especially because of anime, manga, and sports. So the motivation has shifted: Children are now choosing to study Japanese on their own, not just because of their parents. This shift reflects a broad range of factors as well as the deepening relationship between Mongolia and Japan.

Travel between the two countries has become easier, and now anyone can go to Japan fairly freely. Many families take advantage of school holidays to travel to Japan, bringing their children along. In fact, more and more parents are now saying, "During the next school break, let's make sure to take at least one of the children to Japan." These various factors have contributed to the growth of Japanese language learning.

Q: What is the goal of Japanese language learning in Mongolia's elementary schools? Also, is the purpose language learning or cross-cultural understanding?

A: Dr. Dolgor: Since the Ministry of Education in Mongolia allowed foreign language study in elementary schools, schools are free to offer Japanese classes once or twice a week, depending on the availability of teachers, teaching materials, and student interest. Japanese classes usually start from the second grade, not the first. Some schools teach both hiragana and katakana, while others only teach hiragana. It's not common to set ambitious goals like passing the JLPT N5 or learning a certain number of kanji at the elementary level. The main focus at this stage is to give children a light and enjoyable introduction to Japanese. In many schools, Japanese lessons are only 45 minutes per week. So in summary, the main objective is to help students become familiar with the language in an enjoyable way.

Dr. Erdenebayar Batjargal: Just two days ago, we were given the great honor and privilege of having an audience with Their Imperial Highnesses Crown Prince and Princess Akishino. Both Their Imperial Highnesses graciously received us, and during our meeting, they asked us a thoughtful question: "In many countries, when children begin studying Japanese, it is often because they are inspired by anime or manga. Is that also the case for children in Mongolia?" To that, I responded as follows: "Yes, Your Imperial Highness, indeed. As you mentioned, children are naturally drawn to things they like, and they tend to pursue their interests freely, often without a clearly defined goal. Of course, anime and manga are major influences that spark their curiosity in the Japanese language. But it's not limited to that. Many children are also drawn to traditional aspects of Japanese culture, which they find fascinating.

"At the same time, there are also cases where it is the parents who recommend or even encourage their children to study Japanese, saying that it will be beneficial for their future. In the case of primary and secondary education, students are generally motivated to learn a foreign language, especially Japanese, based on their personal interests, such as anime, manga, or cultural fascination. However, when it comes to university-level students--and I say this as a Japanese language instructor at the National University of Mongolia--their goals tend to be much more defined. Many university students choose to study Japanese with the aim of studying abroad in Japan or finding employment in Japan." So the higher the educational level, the more clearly students tend to articulate their objectives.

Q: What kind of content is included in the textbook Nihongo Dekiru Mon for learning Japanese language and culture?

A: Dr. Erdenebayar Batjargal: One important thing to note is that most of the previous textbooks used in Japanese language education were set in Japan. That meant the settings and situations were often not relatable for Mongolian students--especially younger learners who would suddenly be introduced to unfamiliar Japanese cultural contexts. This often left students feeling confused or disconnected, as the content seemed distant from their own reality.

To address this, Nihongo Dekiru Mon is set in Mongolia. The textbook features scenarios where Japanese teachers or children visit Mongolia and engage in cultural exchange with their Mongolian counterparts. This format allows learners to see Mongolia as the setting and creates opportunities to teach and learn about both Mongolian and Japanese culture in a mutual way. Rather than presenting overly complex aspects of traditional culture, the textbook emphasizes simple, familiar activities that children can enjoy and learn through play. I believe the teachers put a great deal of thought and care into making it engaging and accessible for young learners.

Q: I teach Japanese at elementary, middle, and high schools in Argentina and have to evaluate students on their report cards. In Mongolia, how do schools conduct evaluations and prepare tests?

A: Dr. Erdenebayar Batjargal: As mentioned earlier, the portfolio component of the Nihongo Dekiru Mon textbook includes hand-drawn schedules, self-evaluation charts, paper clocks, and newspaper articles introducing Japan. This was a completely new concept for students--evaluating themselves. Previously, with older textbooks, it was mainly the teacher who determined how much Japanese a student had learned, and students were more passively assessed. With this textbook, however, students are now given the opportunity to reflect on and assess their own learning, which I believe is a major innovation.

Ms. Nakanishi: In the textbook, each topic concludes with a self-evaluation section. For example, children are asked to reflect on how well they understood the topic. If they fully understood, they color in three stars. If they understood partially, they might color in one or two. That said, many Mongolian children tend to color in all three stars. I once attempted to create a rubric-style assessment, which I personally think is also necessary. But I received feedback that it might be too difficult, and unfortunately, I had to abandon the idea. Still, I feel strongly that, thanks to this new approach, students are now more willing to share their own opinions and thoughts.

Before that, when we used textbooks like Hiroko-san no Nihongo, we understood everything about Hiroko-chan's life. We knew, for example, that Hiroko's father was a doctor and that she had a friend named Tom-kun. But at the same time, our students couldn't talk about their own lives. What we've come to realize through using Nihongo Dekiru Mon is this: There's no need for Hiroko-san to be in our students' lives. That was a small but important realization. And seeing these moments, we feel that we are glad we created this textbook.

We've also come to think that perhaps we don't need to rush into evaluations so quickly. In Mongolia, many schools are integrated institutions, covering primary, lower secondary, and upper secondary education within the same school. So the way students are assessed tends to remain consistent throughout their school years. That's why we believe it's okay for students to learn and understand gradually, step by step.

Q: In my home country, India, Japanese speech contests played an important role in encouraging people to start speaking Japanese. Could you please share how speech contests in Mongolia are designed to help learners develop their Japanese speaking skills?

A: As I mentioned earlier, the initiatives we have carried out have mainly been centered on individual students. Many of these students have never been to Japan and have had no direct experience of Japanese culture. That's why we have continued organizing the Japanese Speech Contest to give children an opportunity to learn more about Japan. We also hope that, through programs like JENESYS, they will one day be able to visit Japan and experience its culture firsthand.

The speech contest is divided into a university division and a high school division. One of the most important aspects of the contest is choosing an appropriate theme. To ensure the theme is relatable and appropriate for the students, we first convene the Speech Contest Organizing Committee, where we hold detailed discussions. Since the interests of high school students differ from those of university students and adults, choosing the right theme is very important--and often quite challenging. Once the theme is decided, the process moves smoothly.

About a month before the contest, the theme is announced, and students start by writing down their ideas. They then discuss and refine their speeches with their teachers at school. The teachers guide them in preparing and improving their spoken Japanese, helping them become more confident and articulate. As the contest is now held on a school-by-school basis, each school selects three students to submit their speeches. From these, the school selects the strongest representative speech to move forward. Based on the selected speech, students then begin preparing to deliver their speech in front of an audience and have practice sessions. This process allows students to develop their speaking skills.

【Association of Japanese Language Teachers of Mongolia】

Established in 1993, the Association of Japanese Language Teachers of Mongolia is the only professional organization for Japanese language teachers in Mongolia. It currently has 363 members, including teachers from universities and primary and secondary schools. Since 2000, it has served as an administering body for the Japanese Language Proficiency Test (JLPT), and since 2002, it has cooperated in the administration of the Examination for Japanese University Admission for International Students (EJU). In 2007, the Association launched a subcommittee, the Japanese Language Education Research Group, to promote research activities and share teaching practices. In recent years, it has focused on enhancing the professional skills of Japanese language teachers, including providing support for educators in regional areas.

Dr. Erdenebayar Batjargal

After earning a master's degree from the School of International Relations at the National University of Mongolia, Dr. Erdenebayar Batjargal began his career in Japanese language education in 1995 and has remained dedicated to the field ever since. From 2008 to 2014, he studied at Waseda University's Graduate School of Asia-Pacific Studies, where he earned a second master's degree and completed his doctoral dissertation. He served as secretary-general of the Association of Japanese Language Teachers of Mongolia from 2000 and has been serving as its president since 2016.

Related Articles

Keywords

Back Issues

- 2026.1.23 Weaving Memories of …

- 2026.1. 6 How Japanese-Languag…

- 2025.12.25 Peace Actions Envisi…

- 2025.9.30 The 51st Japan Found…

- 2025.9.30 The Japan Foundation…

- 2025.9.30 Bringing the World C…

- 2025.9.30 The 51st (2024) Japa…

- 2025.9.30 Japan Foundation Pri…

- 2025.9.30 Japan Foundation Pri…

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…