Koki Tanaka x Mika Kuraya: Preparations Underway for the Summer! Japan Pavilion at the 55th International Art Exhibition, the Venice Biennale

Koki Tanaka

Mika Kuraya

The Japan Foundation is proud to present the Japan Pavilion at the 55th International Art Exhibition of the Venice Biennale, to take place from June to November 2013 in Italy.

To represent Japan, we have selected as exhibiting artist Koki Tanaka, and as curator Mika Kuraya (Chief Curator, Department of Fine Arts, The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo). In November last year, we hosted a talk event inviting these two figures to discuss about the progress in the preparations for the Japan Pavilion and the process of creating new works for display.

The following article delivers a digest of the event.

KURAYA: Hello, I'm Mika Kuraya, a curator at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo. I've taken charge, with Koki Tanaka, of the Japan Pavilion at the 55th International Art Exhibition of the Venice Biennale.

The selection process for the content of the Japan Pavilion takes a quite interesting system. The Japan Foundation invites curators, and not artists, to take part in a competition. So in this competition, I made a presentation and submitted Mr. Tanaka's ideas on his behalf.

Once the competition is over and the content is selected, the leading role shifts to the exhibiting artist. I made the initial presentation to the Japan Foundation's committee on international exhibitions in May 2012. Between then and now, as you might imagine, Mr. Tanaka's ideas have changed to some degree, and so have mine. Today, I'd like to discuss how the overall concept has changed since that first presentation in May, and how we're making progress in creating the actual exhibit.

Initial ideas submitted in the competition

KURAYA: First, let's talk about our ideas at the time of the competition. The Japan Pavilion, located in the main venue of the Venice Biennale, the Giardini, is an almost perfect square. Piers on the first floor support the exhibit space on the second. With this structure, it looks almost like a box floating in midair. The initial plan, put simply, envisioned displaying videos and photographs, and maybe memos related to each project, in this second-floor box.

KURAYA: First, let's talk about our ideas at the time of the competition. The Japan Pavilion, located in the main venue of the Venice Biennale, the Giardini, is an almost perfect square. Piers on the first floor support the exhibit space on the second. With this structure, it looks almost like a box floating in midair. The initial plan, put simply, envisioned displaying videos and photographs, and maybe memos related to each project, in this second-floor box.

These videos and photographs would share a common element, that's frequently evident in Mr. Tanaka's work--the element of "task." On top of that, we felt it was the duty of the Japan Pavilion to represent, in one way or another, our nation's experiences in the Great East Japan Earthquake of March 11, 2011. On that day, Mr. Tanaka was in Los Angeles, and I happened to be in Singapore. Neither of us was affected directly by the earthquake or tsunami. How, then, could two people who haven't actually experienced the disaster express its impact? That question led us to the overall theme of the project, that is, to explore its possibilities through the exhibition.

TANAKA: I'm now planning to show new videos in Venice, and they're based on certain works I've done in the past--the 2012 project a piano played by 5 pianists at once and the 2010 a haircut by 9 hairdressers at once. My ideas for the Japan Pavilion revolve around these two projects through which I'm trying to pursue forms of collaboration. How do people cooperate with one another and work together? Or, alternatively, what are the things that might happen during that process? I hope to present both the difficulties and the beauties in collaboration, and it's a theme that has been on my mind recently.

TANAKA: I'm now planning to show new videos in Venice, and they're based on certain works I've done in the past--the 2012 project a piano played by 5 pianists at once and the 2010 a haircut by 9 hairdressers at once. My ideas for the Japan Pavilion revolve around these two projects through which I'm trying to pursue forms of collaboration. How do people cooperate with one another and work together? Or, alternatively, what are the things that might happen during that process? I hope to present both the difficulties and the beauties in collaboration, and it's a theme that has been on my mind recently.

The new pieces I'm working on now are a poem written by 5 poets at once (first attempt) and an untitled project involving two groups of people at a fire escape--one group ascends the stairs, the other group descends the stairs, at the same time while making as little noise as possible. These are both extensions of the previous projects.

Ms. Kuraya mentioned the element of "task." Some projects I have in motion for the Japan Pavilion fall within the framework of "precarious task." The one titled swinging a flash light while we walk at night, for instance, involves a large group of people roaming the dark streets, visiting parks, and taking photographs, all by the light of flashlights.

You might very well wonder if this constitutes artwork, but this, too, is an extension of the projects I mentioned earlier. While all of these projects conform to the same established theme, it's also important that some make a detour. This is difficult to explain... The exhibit will be a collection of ideas consisting of layers and layers of less-than-artwork. Collectively, as I perceive, they form one big "precarious task."

I plan on posting the individual videos on my website as soon as they're completed. Most of them should be available before the opening of the Biennale.

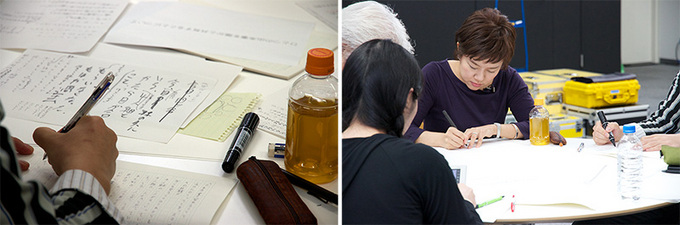

title: a poem written by 5 poets at once (first attempt)

year: 2013

material: HD video

credit: commissioned by japan foundation

equipment support: ARTISTS' GUILD

title: a behavioral statement (or an unconscious protest)

year: 2013

material: HD video

photo credit: Takashi Fujikawa

credit: commissioned by japan foundation

Filming in cooperation with Korean Cultural Center, Korean Embassy in Japan

equipment support: ARTISTS' GUILD

title: #1 swinging a flash light while we walk at night

year: 2012

form: collective act

material: photograph and text

size: 730X1100mm

credit: created with blanClass, yokohama

Two projects forming the basis of the exhibit

KURAYA: Could you tell us more about the two original projects?

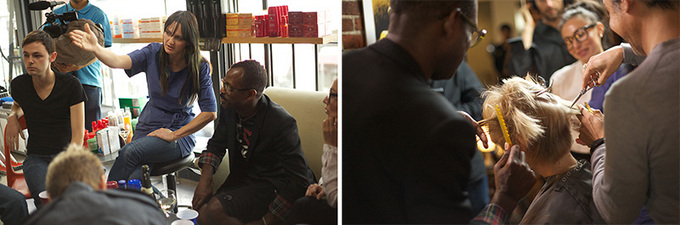

TANAKA: OK, let's start with a haircut by 9 hairdressers at once. I made this video in 2010 in San Francisco. The project is about nine hairdressers cutting the hair of a single model.

Hairdressers normally don't engage in a collaborative haircut. So the task starts with a thorough discussion of the process. How much each hairdresser knows about hair, what each would do given this particular model--they talk all this over and decide how to divide the task, and finally start cutting.

As you might expect, it doesn't work. The plan they had agreed at first gradually crumbles. One hairdresser intervenes in another's work. Some start cutting without any words. Three, and even four, end up cutting at the same time.

KURAYA: How is the model taking all this?

TANAKA: She looks very, very nervous. Incidentally, many of these hairdressers charge something like $200 for a haircut. So if I had actually paid them for participating in the project, it would have cost a small fortune.

KURAYA: That adds up to a $1,800 haircut.

TANAKA: If anyone is interested in watching the film, I've posted it on Vimeo.

title: a haircut by 9 hairdressers at once( second attempt)

year: 2010

material: HD video

time: 28 min

photo credit: Tomo Saito

credit: created with yerba buena center for the arts, san francisco

a haircut by 9 hairdressers at once (second attempt) from Koki Tanaka on Vimeo.

TANAKA: Next is a piano played by 5 pianists at once. This video is from early 2012.

I made it for the Art Galleries of the University of California, Irvine. The request was to create a work using the university's students and equipment. So I asked five students of piano in the music department to compose a single track.

Two of the students major in jazz; the other two study in classical music; and one is a composer and improviser. At first, the best they can do is squeeze onto the bench and figure out a way to get all their hands on the keyboard. Although their positions are settled, it doesn't work well, because each pianist has a different playing style, a different philosophy of music. But then they take what doesn't work, and express it through the piano, and ultimately make it blossom into a piece of music. This whole process, of finding how to play the same piano at the same time, is captured on film.

What interested me in this project was that throughout its duration, the pianists discussed this situation they've been thrown into: Where are they heading to? How are they going to pull it off? They debated these questions nonstop. The camera crew, by the way, was also made up of students. In a sense, this was a drawback--the filming techniques aren't exactly perfect--but it also built awareness and forced everyone there to be a member of the collaboration. The video is my work. But in reality, all I did was create the situation.

This is an important piece of work to me. Every time I reach the end of the video, I can't help watching it all over again. It really offers a valuable lesson.

title: a piano played by 5 pianist at once(first attempt)

year: 2012

material: HD video

time: 57min

credit: created with University Art Galleries, University of California, Irvine

A Piano Played by Five Pianists at Once (First Attempt) from Koki Tanaka on Vimeo.

KURAYA: When you were in Japan, your videos often featured objects that appeared to be moving on their own, or that stressed repetitive movement. Then, after you moved to Los Angeles, you started to focus on collaborative elements in your work. Why the change?

TANAKA: Until around 2004, I tried to keep myself out of my own video work. Eventually, I came to realize this imposed certain limits and so allowed my hands to appear in the video. This was when I made buckets & balls, in 2005, as my graduation project for Tokyo University of the Arts. Once I'd decided to show my hands in my work, I figured why not the rest of me. And I made everything is everything for the 2006 Taipei Biennial. Quite a few of my works thereafter feature other people, too.

When I had reached the stage where I was finished exploring objects, the next thing I wanted to record was uncontrollability. And that was people. Objects are controllable to a certain extent, but people aren't.

This does entail arranging a specific site and situation, and setting down certain rules for the participants. But beyond that, I give them no direction, but absolute freedom. The participants are free to walk out on the project midway, or to refuse to complete a task. I follow this method for my work especially from around 2010 onward.

KURAYA: Both 9 hairdressers and 5 pianists capture multiple people working together to complete a single task. Another thing they have in common is that the participants are professionals--in one case, hairdressers with professional training, and in the other, students receiving specialized education in music. These people share a common knowledge based in their craft.

KURAYA: Both 9 hairdressers and 5 pianists capture multiple people working together to complete a single task. Another thing they have in common is that the participants are professionals--in one case, hairdressers with professional training, and in the other, students receiving specialized education in music. These people share a common knowledge based in their craft.

As you watch the 9 hairdressers, you can also understand the participants' thought process. They all approach the head in sections, like front and sides. They deal with the head as professionals do. And once you see the head through their eyes, you figure out how they plan to divide their roles, how they plan to collaborate. This common professional knowledge isn't obvious at once, but it comes through gradually.

The plan appears to be solid enough. But in the video, it doesn't work as smoothly as it should. They do complete the haircut, and it's good, but you aren't quite sure if anyone is completely happy with it. When the video ends, you aren't at all left imagining that the nine hairdressers later became friends because they've created a single haircut together. You're left simply a witness to a complex process.

One more thing the two works have in common is the element of creation. 9 hairdressers can be interpreted as a process of creating, or sculpting a round object--the head. 5 pianists is similarly complex. Five adults is just the right number for the project. With any more, not all could sit and play the piano at once. But with any fewer, each person would have access to a larger number of keys, and the task would become too easy. The project is well thought out. Given this situation, they even change their positions as if one participant suggests he shouldn't be playing the bass notes all the time. This process of making up rules is, in a sense, like the process of sculpting the atmosphere. Not just being given a collaborative task and working on it, the participants form layer upon layer of creation at the same time.

Installation reflecting Japan at present

KURAYA: Now, let's discuss the specific differences between the initial idea and the current one for the Biennale. The biggest difference, I would say, is in the installation plan.

TANAKA: That's right. Initially, I planned to ask various architecture professionals to design booths using blankets, sheets of aluminum, lumber, and cardboard boxes. My idea was to gather people specializing in different genres in the field of architecture--one might be an architect with his own studio, another might be a builder--and have them make a diversity of spaces under one roof. But I've changed my mind.

Currently, I'm hoping to recycle part of the installation created for the Japan Pavilion in the International Architecture Exhibition in 2012. That is, I want to give my work a sense of intervention into the previous architecture exhibition by incorporating its remnants in some way.

no title for the installation

year: 2012-2013

form: recycle

duration: two years

cooperation: japan pavilion, architecture biennale, 2012

KURAYA: This is my personal view judging from your recent works--I think you're trying to depart from the conventional process of creating expensive installations and disposing them when their time is over.

In Yokohama Triennale 2011, for instance, your installation consisted of pedestals and sofas lying around in the museum storage. And your current installation (at the time of this event in November 2012) in the second-floor elevator hall at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, is a pile of chairs left over from the museum's main venues.

TANAKA: Well, the Venice Biennale alternates between Architecture in even years and Art in odd years. It represents a sort of consumption cycle, which I wasn't quite happy with. I wondered if I might somehow break that cycle. That's why I scrapped the idea of asking architects to build brand new booths. I thought I'd make more sense of a statement by recycling the remains of the most recent Japan Pavilion exhibit and doing something new with them.

Plenty of people may have expectations for the Japan Pavilion to address issues related to the earthquake. As for that, I question myself what would be the best approach to express the issues through my work. The key, I think, is a moderate degree of abstraction and distance. Both Ms. Kuraya and I experienced the 3/11 disaster from a distance. Perhaps that's an approach unique to us.

KURAYA: We know some people think the exhibit should reflect more directly the circumstances following the earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disaster. But the fact is Mr. Tanaka and I aren't capable of doing that.

And yet, as I mentioned before, both of us are aware that it's the duty of the Japan Pavilion to address the situation after 3/11 in some way.

At the time I made my presentation in the competition, it was pointed out that we might be too disinterested; and that we might not be qualified to represent a nation hit by such a major disaster. I understand that view. It is true that we didn't have a direct experience of the earthquake or tsunami. We were at a safe distance from Japan on 3/11. But we recognize that even we must explore how better to take the 3/11 earthquake as our own matter. We need to present a logical connection between everyone--us, as well as the people visiting the Japan Pavilion--and this catastrophe.

Kenji Kai, the director of the Activity Support Department at Sendai Mediatheque, mentions there are two types of interested parties--those who "are," and those who "become." He says those who "become" should qualify as an interested party even if they weren't present at the time of a disaster, but if, in its wake, they make an effort to get involved in the aftermath and provide a solution from their unique position.

I think this defines what Mr. Tanaka and I are trying to do. Through Mr. Tanaka's work from before 3/11, I hope that our exhibit will build on the confidence that even people who haven't directly experienced the disaster can relate to it.

What's revealed through collaboration?

TANAKA: One of the participants in a poem written by 5 poets at once (first attempt), Mari Kashiwagi, is here in the audience. Ms. Kashiwagi, could you tell us about your feelings on the project?

KASHIWAGI: Watching the video, and comparing it with the actual experience, evokes so many feelings. To put it plainly, I might say it's disturbing, or disconcerting.

It feels as though a number of wheels are in motion. The first wheel is Mr. Tanaka's idea, the difficulties and beauties of collaboration between poets who normally work alone. And then, it intersects with another one, that is, the issue of vocabulary, or language.

The use of language always comes with a moral responsibility. Even with a subject that isn't necessarily heavy, a poet is pressed to make a decision on whether it is the word really appropriate for the given context. Perhaps everyone, not only poets, face this problem at one time or another.

What was peculiar about the project was that this responsibility fell on my shoulders in a very different way in that space, during that time. I might have used the strong expressions that I wouldn't choose if I had been working alone.

My personal impression of the finished poem is that it reads like a piece not all that detached from the 3/11 earthquake. We didn't intend to write about the disaster. And yet our work somehow reveals the depths of our awareness.

KURAYA: I said earlier that the participants in 5 pianists and 9 hairdressers shared a common professional knowledge respectively. This applies to 5 poets, too--the participants all compose poems. And today, I think we unconsciously share another common knowledge, and that is the earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disaster.

This common knowledge embodies both possibilities and risks. When a large number of people are thrown into one grave situation, they face the same problems. This creates the possibility for contact with people they otherwise wouldn't meet under normal circumstances.

On the other hand, this also entails the risk of being treated collectively, such as by nationality or residence. I think now is a time when both these possibilities and risks are coming into view.

Art in Japan, and the art market

Question from the audience: The mood in society has changed a great deal between the months immediately after 3/11 and now. Mr. Tanaka, how has your work, or your approach to art, changed during this time?

TANAKA: Today, I went out and bought a dosimeter. You know, an equipment for measuring radiation. I walked into Yodobashi Camera, and the salesclerk at this major chain store couldn't point me in the right direction. Back in summer 2011, when I came back to Japan, the rolling blackouts had been still implemented. I remember being surprised that many convenience stores had the lights dimmed, and mass retailers of electronics had started carrying dosimeters. Although I'm not too familiar with all that has happened since then, because I'm not usually in Japan, the situation has definitely changed over the past year or so. It seems that people, me included, are no longer on the same wavelength in terms of awareness of nuclear power and natural disasters.

TANAKA: Today, I went out and bought a dosimeter. You know, an equipment for measuring radiation. I walked into Yodobashi Camera, and the salesclerk at this major chain store couldn't point me in the right direction. Back in summer 2011, when I came back to Japan, the rolling blackouts had been still implemented. I remember being surprised that many convenience stores had the lights dimmed, and mass retailers of electronics had started carrying dosimeters. Although I'm not too familiar with all that has happened since then, because I'm not usually in Japan, the situation has definitely changed over the past year or so. It seems that people, me included, are no longer on the same wavelength in terms of awareness of nuclear power and natural disasters.

A few days before that, I went to see "Artists and the Disaster - Documentation in Progress -" (October 13-December 9, 2012) at Art Tower Mito. The exhibition presents works of art produced from March 11, 2011, to the present, in chronological order. Basically, it shows what various artists have been up to during this time.

The first room contains works released immediately after the quake and tsunami, and the explosion at the nuclear power plant. Many of these works look more or less complete--like artworks. After that, because a growing number of artists engaged in volunteer work, there are fewer pieces which appear to be art in a general sense. And toward the end, again there are more artistic pieces.

I found the exhibit frightening, actually. It wasn't only about art. It was about the artists themselves. Their conscience, their ego--everything was laid bare.

KURAYA: By the time the 55th International Art Exhibition opens in June 2013, even more time will have elapsed since 3/11. I suppose what I hope for most from Mr. Tanaka is that his work won't be too influenced by the passage of time. Instead of making direct reference to the disaster, I hope that Mr. Tanaka will play up his unique style of abstraction to make the message embodied in the works live on beyond the exhibit.

TANAKA: I might add that, to me, the 3/11 earthquake isn't necessarily the only disaster. Any calamity can break out at any time. Even war is no exception. Extraordinary circumstances may strike when we least expect them. It's a sort of mission of mine to address through my work how we face these circumstances--any circumstance. All this may sound like I'm evading the real-life problems of post-3/11. But I believe that with just the right degree of abstractions and detours, my work can deliver a message, too.

Question from the audience: You said you were trying to depart from the consumption cycle of the Venice Biennale. Could you elaborate on that?

TANAKA: The Venice Biennale, by and large, is inclined to feature artists who are market favorites. Of course, of the countless exhibits, several are dedicated to alternative, experimental installations. But the epithet "Olympics of Art" says it all. This is without no doubt the international exhibition for national prestige.

Let me put it this way. Most countries select exhibiting artists with the power to secure a win in the brief ten-minute presentation to the panel of judges. This usually means they're looking for an exhibit with impact, one that instantly captures the heart. But I'm not about to spend a year of my life for just ten minutes. I'm out to do something completely different. I'm working out a means at the moment.

KURAYA: It's true. Many countries do select big-name artists based on the prediction, or hope for winning the Golden Lion. In 2009, for instance, the US pavilion selected Bruce Nauman and in fact won the prize. It's a general trend the world over. And yet there are exceptions. The Japan Pavilion has always been unique. It has built a reputation for itself by steering clear of the wave of commercialism and making a point of promoting budding artists. At least, that's my understanding.

Widespread protests by student activists in the 1960s and '70s once threw the Biennale in disarray. Many artists boycotted the 1968 event in a revolt against the systematic race for the Golden Lion and the forced rivalry between nations. But even in this year, Japan selected a group of young and emerging artists including Jiro Takamatsu.

At the present moment, artists from the 1970s are all the rage in the world of art. I'm sure if someone like On Kawara were selected now, it would give art professionals high hopes for winning the Golden Lion. But the Japan Foundation selected Mr. Tanaka. I have the greatest respect for that decision.

Mr. Tanaka has come up with the idea of recycling leftovers from the previous Biennale, and showing videos that demand the viewer's attention for 30 minutes, an hour, even a full day, but in return promise to deliver the subtle nuances of issues that relate to us all. His work carries a great deal of significance.

TANAKA: In 2003, Fischli and Weiss made a slideshow installation that you couldn't watch in full even if you spent a week in the Swiss Pavilion. That's the kind of exhibit I'm after.

(Recorded on Thursday, November 1, 2012, at the Japan Foundation's JFIC Hall "Sakura" / Edited by Taisuke Shimanuki / Photographs by Kenichi Aikawa)

Koki Tanaka

Koki Tanaka

Born in 1975; currently lives and works in Los Angeles. In his diverse art practice spanning video, photography, site-specific installation, and interventional projects, Koki Tanaka visualizes and reveals the multiple contexts latent in the most simple of everyday acts. In his recent projects he documents the behavior unconsciously exhibited by people confronting unusual situations, in an attempt to show an alternative side to things that we usually overlook in everyday living. He has shown widely in and outside Japan: the Mori Art Museum (Tokyo), the Palais de Tokyo (Paris), the Taipei Biennial 2006, the Gwangju Biennial 2008, the Asia Society (New York), the Yokohama Triennale 2011, the Witte de With (Rotterdam) and the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts (San Francisco). He recently participated in "Made in L.A." at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles in June 2012.

http://www.kktnk.com/

Mika Kuraya

Mika Kuraya

Chief Curator of the Department of Fine Arts, The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, Mika Kuraya earned her MA at Chiba University. Her recent curatorial projects include: "Waiting for Video: Works from the 1960s to Today" (2009, the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo; co-curated with Kenjin Miwa), "Lying, Standing and Leaning" (2009, MOMAT), "Meaningful Stain" (2010, MOMAT), "On the Road" (2011, MOMAT), "Undressing Paintings: Japanese Nudes 1880-1945" (2011-2012, MOMAT). Recent critical studies include: "Where is Reiko? Kishida Ryusei's 1914-1918 Portraits" (Bulletin of the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, No. 14, 2010).

Keywords

- Photo

- Venice Biennale

- The National Museum of Modern Art Tokyo

- Committee on international exhibitions

- The Giardini

- Great East Japan Earthquake

- Los Angeles

- Singapore

- San Francisco

- Piano

- Hairdresser

- Vimeo

- University of California

- Jazz

- Classical music

- Tokyo University of the Arts

- Taipei Biennial

- Yokohama Triennale

- Sendai Mediatheque

- Kenji Kai

- Mari Kashiwagi

- 詩

- Yodobashi Camera

- Radiation

- Dosimeter

- Convenience store

- Rolling blackouts

- Art Tower Mito

- Bruce Nauman

- Jiro Takamatsu

- On Kawara

- Fischli and Weiss

Back Issues

- 2025.6. 9 Creating a World Tog…

- 2024.10.25 My Life in Japan, Li…

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.5. 2 People-to-People Exc…

- 2024.5. 2 People-to-People Exc…

- 2023.12. 7 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2023.6.16 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2023.4.24 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2022.12.27 Living Together with…