"MAU"--Dancers from Five Asian Countries Come Together to Give a Collaborative Performance, with the Artistic Staging Director Fujima Kanjuro

Fujima Kanjuro

Kabuki choreographer

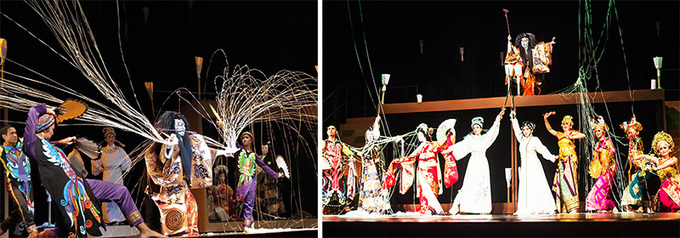

To celebrate the 40th Year of ASEAN-Japan Friendship and Cooperation, dancers from Indonesia, Philippines, Malaysia, Singapore and Japan took part in a performance project named "MAU: J-ASEAN Dance Collaboration" and in November 2013 toured the four countries other than Japan. Using the theatrical technique and artistic effects of Japan's Kabuki theater, to connect the traditional dances of the four ASEAN countries and of Japan, the performances made an impact on audiences in those countries and achieved a new model of dance performance. Kabuki choreographer Fujima Kanjuro, the current head of the Soke Fujima Ryu school of Japanese traditional dance (Nihon Buyo), served as the project's artistic staging director, and we asked him to reflect back on how he successfully mixed Kabuki and the ASEAN countries' traditional dances into a collaborative production.

A collaborative performance of five country's traditional dances

Overcoming the language barrier

──As the director of this stage project, which involved dancers and musicians from five countries, what kind of production were you aiming to create?

FUJIMA: The decision was already made to put on performances in the four countries other than Japan, so my first consideration was to stage a production that could be easily understood by audiences in all those countries. What's more, I wanted the dancers to express the essence of their own countries' dances to the full. It was also important for the performances to contain variations in tempo. If passionate scenes continue for too long, they will tire the audience, while a long stretch of slow tempo would bore the audience. The producer, Hisashi Ito, suggested that there should be a storyline with a wide variety of elements so that the audience would feel as if they were watching a revue taking place before their very eyes.

FUJIMA: The decision was already made to put on performances in the four countries other than Japan, so my first consideration was to stage a production that could be easily understood by audiences in all those countries. What's more, I wanted the dancers to express the essence of their own countries' dances to the full. It was also important for the performances to contain variations in tempo. If passionate scenes continue for too long, they will tire the audience, while a long stretch of slow tempo would bore the audience. The producer, Hisashi Ito, suggested that there should be a storyline with a wide variety of elements so that the audience would feel as if they were watching a revue taking place before their very eyes.

──The storyline was easy to understand: conquering evil.

FUJIMA: In a situation where audiences may not have been familiar with the various languages involved, we had to find a theme that would appeal to them, such as a love story or defeating an enemy, and came to think that any audience would be fascinated by a story involving human beings tackling non-human foes such as ghosts and evil spirits. But since we were putting on these performances in four countries, it wouldn't do to give the impression that people of different nations were fighting each other. So we decided to have the Kabuki actor play the role of the villain and have dancers from the other countries as well as Japan join each other in overcoming the enemy. In that way, we wouldn't be suggesting that countries were fighting each other and so audiences could enjoy the performance as good entertainment.

──What was the reason for choosing a classic Noh play, Tsuchigumo (Ground Spider)?

FUJIMA: Tsuchigumo is the story of how the warriors of Lord Minamoto no Yorimitsu, who were being tormented by a phantom spider throwing threads at them, manage to overcome the evil creature. The story is simple and very entertaining. I sometimes play Tsuchigumo with my father on the Noh stage [editor's note: Fujima's father is Noh actor Umewaka Rokuro], and performing the phantom spider throwing the threads and the worriers then getting entangled in them creates a very amusing scene. The actual movement is just a matter of the phantom spider hurling paper ribbons but the effect is very picturesque. In the classical repertory, it stands out as a truly entertaining dance, and it survives to this day as a piece that has the ability to attract audiences of any nationality.

──The opening of the second act was impressive. There were five boxes arranged on the stage within each of which dancers from the different countries were waiting their turn to come. After the appearance of the Kabuki clown, they each began to dance in their boxes to the same music.

FUJIMA: The opening of the second act has an important meaning. With any production, if the audiences are impressed by the first act, they will spend the interval full of expectation of even more excitement to come. In that mood the second act begins, so it would be fatal if things didn't work out as imagined. In this performance, after the start of the second act, there isn't a climax until the appearance of the phantom spider, so it's even more important that the opening succeeds.

──Why was flamenco music used throughout that segment?

FUJIMA: In order to get the audience into the mood, I used a flamenco piece that I'd played in a previous production. Usually in Kabuki, the songs and dance movements are closely linked, so the lyrics are very important. But since these performances were being put on abroad, Japanese words would not be understood. At the same time, translating them into other languages would be difficult. Even if we did translate the songs, it would be difficult to convey their full meaning in the true sense. So I made the bold decision of taking away the songs altogether. The flamenco music is a piece I composed for a play I put on a while ago. It's based on the classical Kabuki style but it has the addition of a Western rhythm with castanets. I thought this would grab the audience's attention. In this production, I was acutely aware of the need to capture the audience's attention through the visual and musical effects.

──You only had one week of joint rehearsals with the five nations. What was the biggest challenge?

FUJIMA: The language problem. Apart from the Philippines, English wasn't spoken by the artists, so we didn't have a common language. The dancers from each country couldn't understand each other, so it was difficult to communicate. When I gave instructions, I wasn't sure they understood what I was saying, and I was worried that they wouldn't get a clear picture of what I wanted them to do. Though, the interpreters had the hardest time, I guess.

But even in the Kabuki theater, the longest time we have to rehearse together is about one week. Every actor is a synthesis of the arts in itself, with plenty of experience and pride in his skills. This time, it was a gathering of professional dancers and musicians, so from the basic standpoint, they knew what was required to aim for the same target.

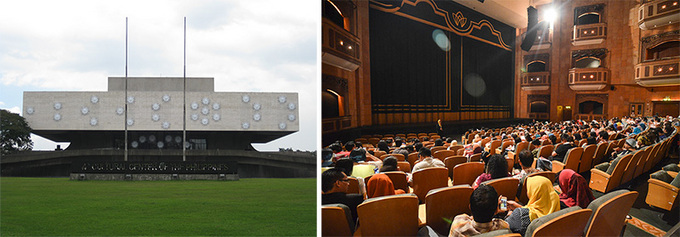

Theater Hall Jakarta (Indonesia)

(Left) Cultural Center of the Philippines, (Right) Istana Budaya (Malaysia)

Creating a collaborative performance while making the most of individual talent

──It must have been very difficult to create a collaboration of such different dances.

FUJIMA: I have frequent opportunities to perform with my father who is a Noh actor in a collaborative play of Noh and Nihon Buyo, but I always try not to harmonize or compromise too much. After all, we are father and son so there is a danger of encroaching on each other's dance style. If that happened, we would end up unable to convey what we would be aiming at through our collaboration. I would warn myself, saying, "No, no, that won't do" and regain my composure. In a collaborative work, Noh should stick to Noh, and Nihon Buyo stick to Nihon Buyo. We should each stay with our own genre.

FUJIMA: I have frequent opportunities to perform with my father who is a Noh actor in a collaborative play of Noh and Nihon Buyo, but I always try not to harmonize or compromise too much. After all, we are father and son so there is a danger of encroaching on each other's dance style. If that happened, we would end up unable to convey what we would be aiming at through our collaboration. I would warn myself, saying, "No, no, that won't do" and regain my composure. In a collaborative work, Noh should stick to Noh, and Nihon Buyo stick to Nihon Buyo. We should each stay with our own genre.

In 2008, I had the opportunity to perform with my father and the Russian ballerina Maya Plisetskaya, but each time, Plisetskaya would improvise. Since she changed her steps at every performance, my father and I couldn't dance in the way we had planned at rehearsals. In the end, the three of us decided not to take much notice of each other. We would synchronize if the opportunity arose and then revert to concentrating on making the best of one's own dance. As a result, it turned out to be a successful collaboration. On that occasion, I realized that my job was to do what I had to do, sometimes reflecting on how I was dancing, and do my best to immerse myself in the emotions that were present on the stage.

──So the secret of a successful collaboration is not trying too hard to harmonize with the other dancers?

FUJIMA: That's right. In a situation where you have dancers from different cultures and languages performing on the same stage, they should be able to communicate with each other and have a dialogue through their "emotions". If those emotions collide, I believe they will produce a fascinating performance.

──I see. At the opening of the second act that we were talking about earlier, the dancers actually performed as if they were having a dialogue. Each box is lit up in turn and it becomes the cue for the artists to start performing their country's traditional dance. It's a fascinating way to enjoy the various national dances to the full.

FUJIMA: In fact, what I requested the dancers was, "When the light goes on in your box, you are free to dance as you like, and when the light goes out, please stop." That was all.

──That was all you said?

FUJIMA: Yes. I did tell them in which order the boxes would be lit up, and when the lights went on, they had 30 to 40 seconds to dance as they liked. But these instructions worked well because the flamenco music was the same throughout the scene and the artists were united in the common determination to dance to the best of their ability.

──You regularly work with Kabuki actors from different schools to create a unified performance. I think this must have something to do with your success in getting the artists from five nations to understand that everything would work out well if each dancer responded in full to the needs of their respective role.

FUJIMA: I believe my duty is to bring out the best in each artist in the interests of creating a performance. Of course everyone must cooperate towards the same goal but, at the same time, it is very important to bring out the individual characteristics of each artist.

That applies, of course, to the opening of the second act, but it also applies to the last scene where the dancers from different nations fight it out with the phantom spider. All of the dancers followed my choreography, but I didn't ask them to dance in the Japanese way. I showed them the movements in the Nihon Buyo style, but then I said, "Please arrange this in the way that would be natural for your country's style of dancing." The result was 15 artists all dancing in their own style without distracting one another.

The dancers from the five countries

(Left) Philippines, (Center) Malaysia, (Right) Singapore

Rapport between the artists and audience gives the performance a lift

──Where did you get the biggest audience response?

FUJIMA: I wasn't able to go to all the different venues, but I've heard that the response in each country was unique to one another. For instance, the audience in Jakarta was very quick to react and laughed at the slightest gestures, and the performance was a big success. In Manila, I heard the performance was greeted with a standing ovation as the curtain fell.

In a stage performance, when there's a mutual response between the artists and the audience, a sense of unity emerges. If the audience reacts in the way we want it to react, then the artists are encouraged to do even better. If there's an enthusiastic curtain call on the first night, it gives the artists a lift and they arrive at the theater the next day feeling very happy. And so, when these responses are repeated again and again, the whole production rises to a higher level.

──Finally, could you give us your reflections on this project?

FUJIMA: I've had the opportunity to work with artists from other countries in the past, but this was the first time I collaborated with people from multiple countries at one time. We didn't have a common language and had different types of food and customs. That's why I had misgivings at the onset. Would it really work out? Would we understand each other? But once we got onto the stage, I found that we were all artists. If I tried to convey an idea, I found that they responded a hundred-fold to what I was saying. That is the meaning of being a "professional." And on a stage, where professionals work together, the barriers come down and we the performers can become one whole.

In that sense, Kabuki is the same. Kabuki actors belong to their various family guilds and schools. Not only do they perform on the Kabuki stage, they also appear on TV and radio. As I mentioned earlier, each actor is a synthesis of the arts in itself, so it is very fascinating that a variety of such actors can come together to work on the same production in the field of performing arts. Thus, this project turned to be a valuable chance to reaffirm this very important aspect.

(Interviewed and edited by: Keiko Tsuji / Interview photos taken by: Atsuko Tanaka)

Fujima Kanjuro

Fujima Kanjuro

Born in 1980, Fujima Kanjuro is a Kabuki choreographer. He is the head of the Soke Fujima Ryu: Fujima School of traditional Japanese dance (Nihon Buyo). His grandfather, Fujima Kanjuro VI was the highly acclaimed choreographer and dancer who was eventually recognized as "Living National Treasure" by the Japanese government and whose oeuvre included a large number of prominent works. His mother Fujima Kanso III, is also an active Kabuki dance choreographer. In 2002, at the age of 22, he formally received the Kanjuro name, becoming Fujima Kanjuro VIII. He received the Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Art Encouragement Prize's New Artist Award in 2003. In 2012, he was awarded by Japan Arts Foundation for his contribution to the traditional arts.

http://www.soke-fujima.com/

Performing Arts Network Japan, Artist Interview

http://www.performingarts.jp/E/art_interview/0603/1.html

Back Issues

- 2025.11.14 Stories from Both Si…

- 2025.10.24 Dialogue through Ani…

- 2025.6. 9 Creating a World Tog…

- 2024.10.25 My Life in Japan, Li…

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.5. 2 People-to-People Exc…

- 2024.5. 2 People-to-People Exc…

- 2023.12. 7 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2023.6.16 The 49th Japan Found…