A Canadian Rakugo-ka's Witty Take on Traditional Japanese Storytelling

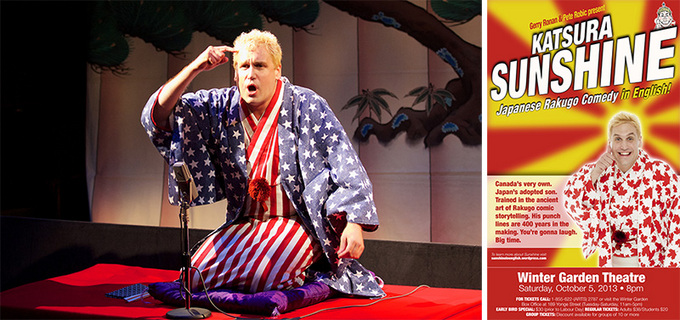

Katsura Sunshine

Rakugo storyteller

Katsura Sunshine, the first-ever foreign professional performer of Kamigata Rakugo (traditional Japanese comic storytelling developed around Osaka), studied under distinguished Rakugo master Katsura Bunshi. Over the past two years, he's been doing a solo tour in his home country of Canada and in cities across the United States, performing his original English versions of Rakugo tales. Since the day he was apprenticed by the great Rakugo master, what has he learned during his time in training, and what stories has he told to audiences in Japan and overseas?

--How was the response overseas? What kind of stories did they like best?

Jugemu was a big hit, as you'd expect. It's a story about a boy with a ridiculously long name, and since the name has no meaning to begin with, the sound itself is enough to make the audience laugh even if they don't understand the language. People also loved Furoshiki, a story about a man who is seeing someone else's wife and has to slip out of her house. It's a classic theme found everywhere in the world. Because Rakugo stories are simple and universal, they don't need to be explained to be enjoyed.

--Have you had any difficulty expressing subtle nuances or punch lines that are unique to the Japanese language?

--Have you had any difficulty expressing subtle nuances or punch lines that are unique to the Japanese language?

In the story called Shukudai (Homework) there is a part where I recite an algebra formula. It's important that I make it sound as literary as possible, as if I'm reciting a poem, so I had to get a little creative translating that part.

There was another time when I adapted a story for English audiences and performed it in an English rhythm, but it didn't go over well. What to do? I tried doing a direct translation of the way my master (Katsura Bunshi) told it, copying his performance exactly with the same pace and rhythm--and voila! The audience burst into laughter. My master really is a genius! It goes to show that you shouldn't mess with traditional art.

There are about 230 stories of my master's original work alone, so I'm just getting started. I'm trying to pick out pieces that would appeal to overseas audiences.

--You originally studied theater history at university in Canada, didn't you?

That's right. A single line runs through Western popular drama, connecting the classical theater of ancient Greece 2,500 years ago to Shakespeare, the opera, operetta, and to musicals, and elements of all these forms of Western theater are found in Rakugo.

I used to write original musicals myself, but I think musicals are not at all realistic. Characters suddenly start dancing on the street, but nobody is surprised? Come on! That's not normal. I also think musicals don't work well with the Japanese language, because it's difficult to rhyme in Japanese. The success of musical lyrics depends on the intricacy of the rhymes.

--What was your impression of Japan when you first arrived 14 years ago?

I didn't know there was so much tradition remaining in Japanese society. The modern and the classical coexisted next to each other. We can still find elements of "wabi (simple, austere beauty), sabi (rustic patina)" and "iki (sophistication)" in the ways of thinking and aesthetics of Japanese people.

--It took eight months for you to be accepted as an apprentice by your master, Katsura Bunshi.

--It took eight months for you to be accepted as an apprentice by your master, Katsura Bunshi.

Yes, but it would have taken the same amount of time, even if I weren't a foreigner. It's a tough world. But I was totally fascinated with the world of Rakugo, that is, the ultimate monologue.

--What makes it different from English monologues or stand-up comedy?

As a stand-up comedian, I would have entire control of my performance on stage. But there are many rules and conventions in Rakugo shows. Normally, four or five performers appear in one show, which is organized to flow in a certain way. People come to see the star performer who appears at the very end. So, I have to make sure things go smoothly for the senior performers who come on after me, for instance, being careful not to choose the same topic for my prologue and so on. And you can't be clumsy about it--you need to do it with style, and it has to be done naturally, so the audience doesn't notice that you are actually intending it.

I have also learned audiences in Osaka are particular about the Osaka dialect. I once saw a comment on a questionnaire after my performance, which said, "This rakugo-ka (Rakugo storyteller) isn't a real Osakan..." Well.... isn't it obvious?

--During the training, you had to fetch and carry for your master, and there's a strict hierarchical relationship. Was it hard to get used to?

There were rules for everything, for example, correct usage of honorifics, how to clean house, do laundry, and carry my master's bag. It was a grueling three years with no drinking, no smoking and no girlfriend. That's probably what made me so crazy ... and funny!

But if you cut corners, you lose in the end. In fact, and I'm exaggerating a bit here, but it doesn't really matter whether you learn stories during apprenticeship. The most important thing is not to bring shame on your master. Sometimes I didn't understand why I was being reprimanded, but even then, I didn't want to give up. After three years, everything became clear. I realized that it was me that hadn't understood the meaning of obligation, and wished that I'd had this frame of mind then.

--Does that mean kindness or consideration for others?

If I can read my master's, other masters' or my seniors' minds, and understand what they expect me to do, that means I will also be able to read the mood of the audience when I'm on stage. We improve our skills by studying the reactions of others. In Canada or the United States, asserting yourself is important, but that's a Western concept. Things are completely different in the world of Rakugo...although people are not that different when they are drinking, whether in the West or in the East.

--That is a virtue of modesty even the Japanese tend to forget nowadays.

My master, Katsura Bunshi, is a big shot in the world of Rakugo, but he's extremely humble. He often starts his performance with the line like this: "Thank you for coming today, taking time from your busy schedule...but if you were really busy, you wouldn't be here, would you? (audience laughs)." Behind this line is his modesty, saying busy people have other things to do than listen to his Rakugo.

His demeanor also makes his disciples humble. I owe him so much that I couldn't possibly pay him back (it would be presumptuous to even think I could). All we can do is pass on the lessons we've learned to the younger generation. I could never have understood these things without the training.

--I hope you will continue to convey the beauty of Japan's spiritual tradition to overseas audiences.

I want to perform again and again, in many other countries, including Slovenia where my roots are. The great thing about Rakugo is that it makes you laugh, even if you already know the punch line. Rather, I think it's the stories you've already heard that you're most eager to hear again.

Scenes from the North American tour

Back Issues

- 2025.7.31 HERALBONY's Bold Mis…

- 2024.10.25 From Study Abroad in…

- 2024.5. 2 People-to-People Exc…

- 2022.11. 1 Inner Diversity<3> <…

- 2022.9. 5 Report on the India-…

- 2022.6.24 The 48th Japan Found…

- 2022.6. 7 Beyond Disasters - …

- 2021.3.10 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2020.7.17 A Millennium of Japa…

- 2020.3.23 A Historian Interpre…