The 48th Japan Foundation Awards―Linking the World through Culture amid the COVID-19 Pandemic <5>

Dr. Irmela Hijiya-Kirschnereit, Professor, Freie Universität Berlin

On Receiving the Japan Foundation Award

June 24, 2022

[Special Feature 075]

Special Feature: "Linking the World through Culture amid the COVID-19 Pandemic: The 48th Japan Foundation Awards (2021)" (for more on special features, click here)

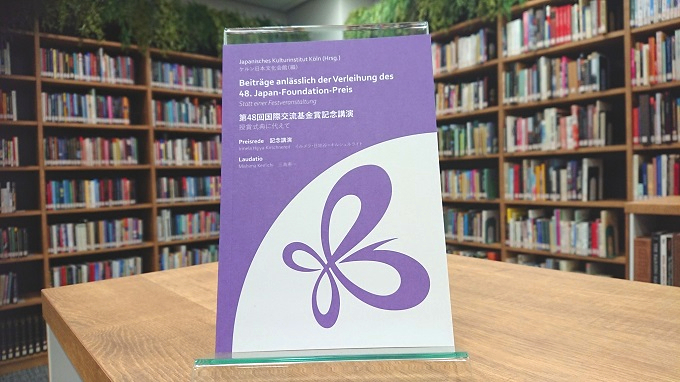

The Japan Foundation (JF) is pleased to announce that the Japan Foundation Awards Commemorative Lecture by Irmela Hijiya-Kirschnereit, ""The Limit of My Language is the End of My World"―Various Forms of Understanding between Japan and the 'West'" which was not held at the Japan Culture Institute, Cologne due to the spread of COVID-19 is instead available as a manuscript included in a booklet (in both Japanese and German). The booklet will be available at the JF Library (Tokyo) for borrowing and viewing from Monday, June 13, 2022.

In the booklet, Hijiya-Kirschnereit talks at length about the various topics that have fascinated her in her research on Japan, the role that language and literature play in our approach to other cultures, and their impact on our thinking, among other ideas.

Also included is an introduction of the award winner by Dr. Kenichi Mishima (professor emeritus at Osaka University), an old friend of Hijiya-Kirschnereit's.

In this issue of "Wochi Kochi," we would like to share with you the acknowledgment by Hijiya-Kirschnereit from the booklet.

We hope you will enjoy the full version available at the library.

Acknowledgement of the Japan Foundation Award 2021

(October 20, 2021)

Irmela Hijiya-Kirschnereit

Asaki yume mishi. Am I dreaming? Am I the butterfly that the sage Chuangtzu (or 莊子 Sōshi in Japanese) dreamed he had transformed into? Or is it a butterfly after all, who dreamed he was Chuangtzu? The news of the Japan Foundation Prize put me in a state of limbo that immediately reminded me of this topos taken up by so many poets in the East Asian region.

My encounter with Japan was probably the most formative event of my life in every respect, after my initial imprint by my own family, my culture, and my time. Like so many in Europe, I discovered Japan for myself early on as an antipode, a place of longing. And in retrospect, I feel it is a great gift that I was able to realise as an adult the way of life I had vaguely dreamed of since my childhood in both cultures and worlds. Studying Japanese culture and literature has enriched me and broadened my horizons. The 7th of July, 1970, when I first set foot on Japanese soil and continued my studies in the country, is an important commemorative day that I celebrate every year. Until three years ago, I was able to happily celebrate the day with my late Japanese husband Shūji. He, who for my sake had since lived many years in a foreign land in Europe, brought so much of his culture and his attitude to life to me in our daily routine that I would probably not have been able to sense otherwise. I very much miss the constant dialogues with him, in Japanese and in German. It's like in every good relationship: there are all seasons, there is good and bad weather, and there is harmony and friction. It's the same with my object of study, Japan, which has constantly broadened my view. And which surprises me again and again. When I began to study the genre of shishōsetsu in the 1970s, it was out of a complicated motivation, because I wanted to understand what made this narrative form so attractive to the Japanese. I had no idea that autofiction would experience such a boom in Western languages in the 21st century. I had a similar experience with Japanese cuisine: I could never have imagined back then that it would gain such an outstanding reputation worldwide in the meantime and that many things that I myself had to learn to savour first, would have gained global acceptance, from umeboshi to nattō and mozuku. Literature as well as food and hospitality culture are two of my fields of research. The Japanese language and script, whose special expressive capabilities I learned to appreciate so much through literature, is another, and a particularly fundamental one for international communication. I am therefore pleased that the largest project in German-language Japanese studies, the Comprehensive Japanese-German Dictionary in three volumes, could be completed this year. I hope that my fascination, appreciation and enthusiasm for Japan can be felt in everything I have been able to do over the past decades in research and teaching, including the promotion of young academics, as well as in public relations and media work. What I have learned in all these years I owe to my superb Japanese teachers and colleagues, friends and fellow human beings. I am grateful from the bottom of my heart for the Japan Foundation Prize, which means a lot to me. And again, a Japanese poem, or rather the Imayō song, comes to mind, which has accompanied me through all these decades as the Japanese ABC and seemed so self-evident and rather inconspicuous to me that I have only gradually begun to appreciate it in its full dimension.

Iro wa nioedo/chirinuru wo,

Waga yo tare zo/tsune naramu

Ui no okuyama/kyō koete,

Asaki yume miji/ei mo sezu.

Related Articles

Related Events

Back Issues

- 2025.7.31 HERALBONY's Bold Mis…

- 2024.10.25 From Study Abroad in…

- 2024.5. 2 People-to-People Exc…

- 2022.11. 1 Inner Diversity<3> <…

- 2022.9. 5 Report on the India-…

- 2022.6.24 The 48th Japan Found…

- 2022.6. 7 Beyond Disasters - …

- 2021.3.10 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2020.7.17 A Millennium of Japa…

- 2020.3.23 A Historian Interpre…