The 48th Japan Foundation Awards―Linking the World through Culture amid the COVID-19 Pandemic <3>

Interview with Miyata Mayumi, shō performer

"Seeking a Sound in Shō that Continues to Resonate across Time and Space"

June 3, 2022

[Special Feature 075]

The second installment of the award-winners' interview for the special feature "The 48th Japan Foundation Awards―Linking the World through Culture amid the COVID-19 Pandemic" (for more on special features, click here)is with shō (Japanese wind instrument) *¹ performer Miyata Mayumi. Used in gagaku court music, which has a history in Japan of over 1,200 years, the shō is believed to have originally come to Japan from China during the Nara period (710-794 A.D.). How did the shō and gagaku develop in Japan, and how are they now giving rise to further collaborations with foreign musicians and across genres? We spoke to Ms. Miyata, who, as a leading shō expert, has been pushing the boundaries of the instrument's potential.

Captivating audiences with stage performances

Captivating audiences with stage performances - ──You've given many shō performances in Japan and abroad. Is there any difference between performing in front of overseas audiences who are not familiar with gagaku and performing in Japan?

- Gagaku has long been relatively obscure in Japan, too, so I don't perceive any particular differences between performing in Japan and performing abroad.

Although I do provide some explanation of the construction and history of the shō, my first priority is for the audience to enjoy listening to the sound.

- ── I've heard that your interest in the shō was sparked by your attraction to the sound itself. Is that the first thing you want to give people a taste of?

- Yes. I just want people to enjoy listening to it.

- ── You spoke at length about the appeal of the shō's sound in an interview with Performing Arts Network Japan. Is it fair to say that you view the sound as not necessarily something typically Japanese, but rather something global similar to that of pipe organs and other foreign instruments?

- Generally, when we hear the term "Japanese music," we probably picture music from the Edo period in the early modern era, from AD 1600 A.D. onward. That means things like the instruments used in kabuki ── the shamisen, yokobue flutes, koto, etc.

The period when gagaku was actively performed was from the Nara period in the 700s to the 1000s A.D. when The Tale of Genji was written, so in that sense it's very old. So for Japanese people, since it is performed at large temples, shrines, and court ceremonies, although there are opportunities to listen to it, it is somewhat remote from their daily lives.

Ms. Miyata receives the Main Prize (certificate) from JF President Umemoto Kazuyoshi at the Japan Foundation Award Ceremony

Ms. Miyata receives the Main Prize (certificate) from JF President Umemoto Kazuyoshi at the Japan Foundation Award Ceremony- ── The shō is often regarded as a Japanese musical instrument, but it came to Japan from China, didn't it?

- That's right. Chinese-derived music, which forms the core of gagaku, arrived from China before the 8th century A.D., and the shō used in Japan today is based on the Tang Dynasty style.

There is a pair of male and female deities, Fuxi and Nuwa, that appear in ancient Chinese mythology. Although she has been passed down as the creator goddess of humanity, Nuwa appears to have originally been a goddess of the Hmong, a minority ethnic group that lived in central China, and it is said that this goddess Nuwa created the shō. The Hmong still highly value the khene and lusheng, which are relatives of the shō, as their ethnic instruments.

As such, I think it may have been the Hmong who first acquired the shō. Although no conclusion has been reached yet, I believe that the Hmong played an important role in the creation of the shō as an instrument.

- ── It is very interesting that the shō, which came from China, became a symbol of Japanese culture. How did the Japanese people of that time adopt it?

- There are quite a few Japanese people who say that the sound of the shō gives them a feeling of nostalgia, and I think that may indeed be true. It must have been the latest music when it first came over from China. Even by the time of The Tale of Genji, it was described as "contemporary," so it must have been an instrument that seemed quite modern and fresh to them. As it was gradually assimilated into Japan, people today view it as something nostalgic.

It's the same with rice, isn't it? We think of rice as the "Japanese soul," but if you think about it, the prevailing theory is that it came from the continent.

Even in terms of the Japanese as an ethnic group, there are plenty of people who migrated to Japan from the continent, and if you look at the genes, quite a high proportion consist of people who have come over from there. Of course, even further back in the past, humans emerged in Africa and migrated from there, probably reaching Asia about 12,000 years ago. It is very interesting to think about how culture is transmitted. For me, it is deeply moving to think about how the world looks completely different depending on what era you choose as a standard.

And yet, once something takes root in a place, over 1,000 or 2,000 years, you get this one completed form of a culture, and you can perceive how each region brings that to completion in its own way.

- ── Listening to the sound of the shō also allows us to think about history, doesn't it?

- We can also think about the history of Japan, from the Heian period (794-1192 A.D.) to the Muromachi period (1333-1573 A.D.), when gagaku was actively performed. In addition to music, the sound of the shō inspires interest because it reminds us that various other forms of culture came to Japan from the continent.

It is also an opportunity to learn about Chinese culture and history, and to wonder what kind of role the shō played in China. For example, during the Han dynasty, the Northern and Southern Dynasties, and the Tang dynasty, exchanges with western countries were becoming more active, so when Emperor Wu of Han made an expedition to the western regions, it resulted in the introduction of various types of culture from the west. In the Tang Dynasty, this interchange became more active, and we can imagine even more. Moving further to the Middle East, Mesopotamia, Egypt, and Greece -- we can imagine how the people perceived the music in Pythagoras' time, or the music of Plato, who admired Pythagoras.

Through one instrument, the shō, I have developed an interest in many other things, and that makes me happy to be engaged with this instrument.

Talking about the joy of receiving the award at the award ceremony

Talking about the joy of receiving the award at the award ceremony Over time, the melodies of gagaku have changed to suit Japanese tastes, but the shō, biwa, and koto have not changed much in their basic musical temperament and this is namely their original twelve-tone scale. The twelve-tone scale is made up of intervals of repeated perfect fifths*². It is a fairly clear tonal system. This took shape in China around the 6th century B.C., as well as in regions further west. This was when Pythagoras discovered his system of tuning ── we call it Pythagorean tuning*³ ── which consists of repeated perfect fifths (intervals based on a frequency ratio of 3:2).

Pythagoras spent many years studying mathematics in Egypt and Babylonia (present-day southern Iraq), so there may be a point of contact between the East and the West in that regard, and there were steady exchanges of instruments in Mesopotamia and Persia. Gagaku retains very strong traces of this kind of ancient international cultural exchange, so it may have a slightly different character from the sound systems, instrumental preferences, and song melodies that underwent changes in accordance with Japanese tastes in later eras.

I thought that since both Western and Eastern music share similar musical roots, perhaps we could feel a sense of kinship in that way. Even if you don't understand the theory or history, I believe that these elements are still present in the music we listen to everyday.

- ── Perhaps it is a remnant of the culture from a time when things were more fluid and not so clearly divided into "the West" and "the East" as they are today. Even mathematicians study music theory, etc., as they did before learning was divided into fields like "art" and "science."

- Yes, that's right. I think that today, in order to explore the nature of our science and art, we are seeing more and more movements that are aspiring to and aiming for a time when things are not so finely compartmentalized.

- ── Trying to put back together something that has fallen to pieces.

- Simply put, it comes down to "philosophy (= love of knowledge)." Whether it is science, literature, art, or music, human beings love knowledge, which leads to a love of human spiritual activities, and I think this involves not only the human brain but also the physical nature of human beings. I believe that people are stimulated by exchanges with various places, and that this leads to local characteristics being introduced and developed over time.

- ── You yourself have collaborated in many fields, such as playing the shō in Teshigawara Saburo's stage version of Rashomon and appearing in the opera TIME directed by Sakamoto Ryuichi ── you seem to cross over genres quite naturally.

- It's not true old things are just old. Old things can be reinterpreted as new things, and new things become old after a few decades or centuries, and then they become new again. Therefore, I feel that what humans perceive with their minds and bodies is a channel of water that runs deep underground, and that this channel flows through various periods of time.

The number of people who play the shō is growing very rapidly now. In addition to those who perform in front of an audience, there are more and more people who perform for fun, and I think we are hearing it being used more and more in commercials and played like pop music.

I myself feel I'm not obliged to promote it or have any desire to popularize it. It may sound selfish, but I just want to feel the sounds and resonances that I want to hear. Even so, I still have responsibilities in terms of performing, and it wasn't until much later that I became fully aware of those responsibilities myself. At first I didn't think about performing in front of people.

- ── It is amazing that as a pioneer among shō performers, you have contributed to its popularization, yet you didn't really give it much thought (laughs).

- The profiles say that I'm a leading expert, but there are many teachers who are masters. In my case, as I traveled abroad with all kinds of people, I became more involved with composers and producers, and my activities expanded as if to say, "well, let's give it a go."

For example, world-renowned composer John Cage composed a piece for the shō, which was inspired by a chat we had at a reception after a concert by TIME (Tokyo International Music Ensemble), organized by (composer) Ichiyanagi Toshi. One day, out of the blue, he said, "Would you like me to compose a piece of music for this instrument?" And I thought, "What?" (laughs) In hindsight, it's pretty amazing, but it wasn't that I'd urged him to write something -- it came about through a relationship with an intermediary.

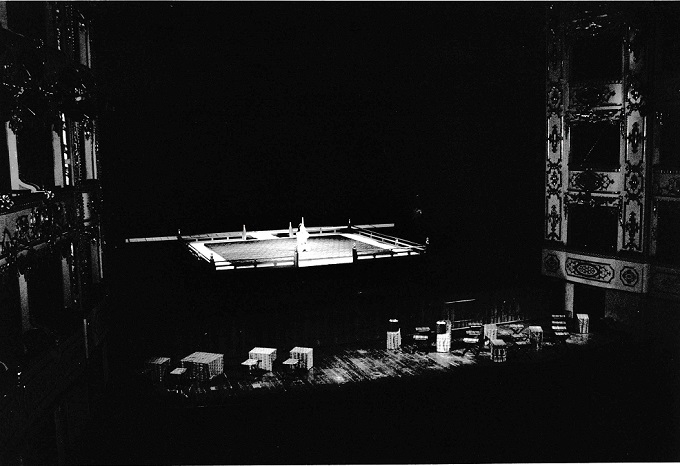

Performance at a recital to mark receiving the Japan Foundation Award, featuring "One⁹" by John Cage

Performance at a recital to mark receiving the Japan Foundation Award, featuring "One⁹" by John Cage - ── When listening to a shō performance, is there anything you would like people to pay attention to?

- More than anything I want people to enjoy the sound.

The shō is made of 17 thin bamboo pipes, but each pipe produces a different sound with a different frequency. Subtracting the lower from the higher of these frequencies produces differentials (difference tones) in the sound. Each bamboo pipe has a rich set of overtones*⁴, and when the sounds of two or more pipes overlap, the overtones are emphasized. These are sounds that are not written in the score. The difference tones somehow seem to echo from a different world, like they are echoing inside my body, so I would be happy if people might hear them and be surprised by them.

The shō is an instrument that plays a background role in gagaku and does not stand out much, but when I play it solo, I can hear the difference tones and overtones distinctly. It is a distinctive feature of the shō that you can hear sounds that are not indicated in the score, and these days, more and more people tell me that they hear these sounds at concerts, and I am very happy to be able to share this feeling with them.

- ── Is it possible to control the sounds that are not in the score?

- You can make adjustments to some extent, but you cannot control them completely. They're generated spontaneously.

The combination of sounds produces various difference tones and overtones. When it comes to difference tones, the number of differences is reduced when the tones are close to each other, so we hear a very low sound, as if the earth is roaring. If they're further apart, it sounds like waves undulating.

Difference tones are created when any instrument produces multiple tones, but in the case of the piano, for example, the sound quickly becomes quieter and quieter, making it difficult to hear the difference. With the shō, the sound can be sustained for longer by inhaling and exhaling breaths, so they are easier to hear.

Difference tones and overtones are also generated by the human voice. A male-only chorus can produce the sound of a female voice, for example. An octave higher of overtones sounds stronger, so when many men are singing, the octave higher sounds are emphasized, making it sound like women are singing. With Gregorian Chants, it sounds as if angels are singing inside the church. The same is true for shōmyō, the Buddhist chanting of sutras by monks as if they were songs. When the monks, all men, are chanting in large numbers, you can often hear a voice an octave higher.

- ── Before overtones were explained, humans were unaware of them, weren't they?

- Perhaps they felt them in their bodies. In the past, the idea of "cosmic harmony" was prevalent in all regions of the world, and I believe that people were able to feel the sounds that their bodies perceived, the sound waves and resonances generated by nature and the universe.

Even now, for example, when there are electrical sounds in a room, such as those of air conditioners, it is difficult to hear the overtones and difference tones. So I hear overtones when I listen in the absence of anything electrical like that, even just when using my voice naturally. I believe that the wonderful choral harmonies of Eastern European and Polynesian peoples were not developed by training, but through the body's own ability to perceive overtones.

- ── That kind of physicality and ability is perhaps something that is often lost in modern life.

- With the development of science and technology, like this online interview, we are able to do things that would have been completely unimaginable in the past, but on the flip side, there are probably some abilities that have been muted.

I don't mean like meditating in the great outdoors, but I would like to strip away extraneous things in such a way. Living on this earth means that each one of us is a cosmic being, and I hope we can regain that kind of feeling.

In 1983, Miyata participated in her first overseas tour as a member of Tokyo Gakusho, a gagaku performance group, including a solo performance at the Reggio Emilia Opera House in Italy

In 1983, Miyata participated in her first overseas tour as a member of Tokyo Gakusho, a gagaku performance group, including a solo performance at the Reggio Emilia Opera House in Italy- ── How would you like to continue your work in the future?

- I would like to go on sharing the interest I have in difference tones and overtones that I mentioned earlier. We can feel these sounds, which appear in both contemporary and classical works, with our bodies, even when the rhythms are not intense, and I hope that we can all resonate with a sense of oneness with the universe by experiencing them together.

Another thing, which I have been working on for the past 15 years, is to perform old scores from the late Heian to Kamakura and Muromachi periods. At that time, the style of performing was a little different from what it is now, and I am currently studying this alongside Professor Endo Toru of Tokyo Gakugei University. I will continue to give concerts that explore various possibilities to create a single piece of music, stripping away modern sensibilities as much as possible, and trying to imagine those of people from long ago.

The predominant image of gagaku, and I include myself in this, is of "elegant traditional classical music," but there is another side to it. As I mentioned earlier, the people of the middle and classical ages had a strong sense of it as something very modern and playful.

In scores from the Kamakura and Muromachi periods, there are many writings that say things like "hurry up here" or "stretch it out there," and if you play the music accordingly, you can reproduce music with a great sense of rhythm. Gagaku is often pigeonholed in terms of its image, and I want to take a fresh look at it from the perspective of the people of Kamakura and Muromachi periods.

- ── It's impressive that you can look at a score from that time and reproduce the same sound today.

- It takes a lot of time, but it's fun to explore the various possibilities one by one, working out that something can be played this way or that, and gradually make them come together as music.

Even with the same piece, the score being played now doesn't have those kind of writings. From the beginning of the 16th century, it became standard to have almost no writings on the score, so I imagine that the trend of gagaku was different during the Kamakura and Muromachi periods compared to later periods.

As such, I try to make the most of what I can read from the score and avoid including my own sensibilities as much as possible, though that doesn't mean producing something sterile with no sense of its own musicality. I aim to make it something vibrant on that basis.

- ── Would you say this is a new production, or a further evolutionary process, rather than simply recreating the past?

- The first thing I want to do is to feel and reproduce the music as people in the past used to enjoy it. That said, since it is a modern person who is giving the performance, it is impossible to say that there is absolutely no essence of modernity in the music. Since the traditional customs of gagaku that I have performed up to now are still there, I may not be able to truly escape from them, but there is a part of me that wants to experience the sensibility of the people of the Muromachi period.

Perhaps this is a trend in today's society, but I think we are seeing a reevaluation of cultural traditions that originated in the Muromachi period, such as shōin-style architecture, the tea ceremony, ikebana, and Noh. So I wanted to revisit that period in terms of music. I think it is interesting that the shō, which was introduced during the Nara and Heian periods and elevated to a higher level in Japan, developed into music that people enjoyed as something of their own in the Kamakura and Muromachi periods. I would like to recapture that feeling, which is my other major goal.

- *¹ Shō: A wind instrument consisting of 17 long and short bamboo pipes bound together in a circular shape. The sound is produced by blowing in and out of a metal reed attached to the base of 15 of the 17 bamboo pipes.

- *² Perfect fifth: One of the intervals indicating the distance between two notes. A perfect fifth consists of two notes seven semitones apart: do and so, re and la, mi and si, fa and do, so and re, la and mi, etc.

- *³ Pythagorean tuning: A tuning based on intervals of repeated perfect fifths (i.e., a frequency ratio of 3:2).

- *⁴ Overtones: Sounds with frequencies that are integer multiples of the fundamental frequency.

November 2021, online interview

Interview and text: Terae Hitomi (The Japan Foundation)

Text: Segawa Yoko (The Japan Foundation)

Related Articles

Related Events

Back Issues

- 2025.12.19 Echoes of a War Unli…

- 2025.6.24 Exclusive Interview:…

- 2025.5. 1 Ukrainian-Japanese I…

- 2024.11. 1 Placed together, we …

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.5. 2 People-to-People Exc…

- 2024.2.19 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2024.2.19 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2023.4.24 The 49th Japan Found…