The 48th Japan Foundation Awards―Linking the World through Culture amid the COVID-19 Pandemic<2>

Interview with Koreeda Hirokazu, film director

"What It Means to Make Films That Transcend National Borders"

March 31, 2022

[Special Feature 075]

This special feature, "The 48th Japan Foundation Awards―Linking the World through Culture amid the COVID-19 Pandemic" (for more on special features, click here), shares interviews and statements from our Japan Foundation Award winners, including three individuals and one organization, regarding their thoughts on their activities. For this first installment, we spoke with director Koreeda Hirokazu about his thoughts on international co-productions and social consciousness in film expression. Following the French co-production La Vérité (The Truth), he is now in South Korea working on a South Korean production titled Broker.

- ――You are currently in South Korea editing a Koreanproduction titled Broker. Are there experiences specific to international collaboration or working with people from overseas that stick out to you?

- That's a hard topic because I never know if what I am feeling is particular to me, or if it comes from my being "Japanese." Say I sense a difference between myself and another person. Are the person's attitudes and ideas just their own, or do all French people share them? It's very hard to know. Get it wrong and you've spent a mere half year there and find yourself saying stupid things about what French people are like. So it's a hard topic. You can refer to "French people," but everyone is different. There is this tendency to talk about "the French" in a big way despite those differences, so I feel I have to be especially careful. As a reminder.

- ――Does the way you communicate and shoot in Japan differ from the way you shoot overseas?

- For sure, the fact that we use interpreters means that language becomes even more important. That said, what I am trying to do with the actors and staff on set is essentially the same, and the conclusion I came to for myself after my two experiences (France and South Korea) is that I don't have to make drastic changes. Just so long as I can communicate my vision so that we have that in common and move in the same direction.

My approach to doing that is not different because the countries are different, but because the people are different. It's certainly not the case that everyone who is Japanese does everything the same way, so it's no different in that respect. There may be some things that are easier for me to communicate to Japanese people, but it's not necessarily the case that things are harder to communicate just because our languages are different. There are ways to communicate that go beyond language and make differences in things like nationality, language or cultural background irrelevant. Indeed, we're all connected through film, I'd say, so why not depend on that?

- ――Did you think it would be like that before you started shooting abroad?

- Well, if I hadn't thought there was a chance that things would be okay, I wouldn't have considered shooting in a different language. Before making the film, I had the opportunity to visit various film festivals, talk with staff and actors from various countries, and teach film classes in foreign countries, and I was surprised to find that the words I speak could be understood. Of course, a strong interpreter is essential, and I don't mean to say it's the same as in Japan, but it seemed doable.

- ――In what ways do you think you understand each other? Is it your passion for film?

- I suppose it's the kind of film we're attempting to make. After all, our passion is a given. Catherine Deneuve (who played a leading role in The Truth) said to me when we were about a third of the way through filming, "If you've done any editing already, I'd like to see the whole thing, including the parts I'm not in." She said it was easier for her to act if she understood the director's view of the world, so I showed her about an hour of film we'd already edited. Afterward, she told me it gave her a good understanding of my wit and humor. After that, her acting was always spot on. That's why I think things will always be okay as long as people share a common view of the world and have a sense of the various directions the film is headed.

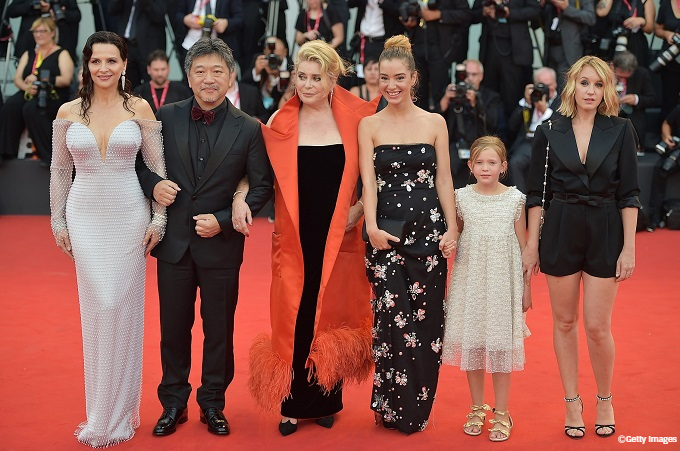

At the 76th Venice International Film Festival, The Truth was officially selected to open the competition. With Catherine Deneuve (third from the left) and other actors

At the 76th Venice International Film Festival, The Truth was officially selected to open the competition. With Catherine Deneuve (third from the left) and other actors- ――What do you do when people have different opinions?

- That's the same as in Japan. You talk about those differences and you work to find common ground.

- ――All scheduled filming for 2020 has reportedly been cancelled due to the spread of COVID-19. Do you think COVID-19 will impact how productions are handled in the future?

- More than COVID-19 countermeasures, the "work style reform" is probably going to extend its reach to Japanese film production as well, and we're at the point where we will soon have to make changes, so I think that will be a big factor.

We were already out of time before the pandemic, given how terrible the work environment on Japanese films is compared to other countries, and as a director, I bear some responsibility for that, too. We've never been able to maintain a schedule for shooting that doesn't require twelve-hour workdays, and now we're at this point and I don't see it being acceptable for much longer.

- ――What do you think about the future of film, including audiences?

- Good question. I mean, there's no way to make a film remotely. I certainly don't believe it can be done without getting people together.

In terms of movie formats, streaming has been growing. COVID-19 probably accelerated that growth, and now we wonder what a movie actually is and what it means for people to go to a movie theater. Issues that were still a ways off are probably now already upon us, and I think we are at the point where we have to face them. That's maybe true for both creators and audiences. Maybe we'll decide it's okay to stream everything. Once we get to the point where movies and movie theaters are treated as totally separate, then basically, major changes to the movie environment will be inevitable, at least as far as viewing is concerned.

Koreeda receives award from JF President Umemoto Kazuyoshi at Japan Foundation Awards Ceremony

Koreeda receives award from JF President Umemoto Kazuyoshi at Japan Foundation Awards Ceremony- ――Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, you proposed the "Asia Lounge" conversation series*¹, a joint project with the Japan Foundation Asia Center at the Tokyo International Film Festival from 2020, to promote exchange and dialogue.

- Yes, because that's what films festivals are originally for. So, what we're trying to do with the "Asia Lounge" is completely inconsistent with COVID-19. What we've managed to accomplish during the pandemic doesn't feel like even one-third of what we're hoping to do. Because, until the pandemic settles down, people can't get together. It's as true for film festivals as it is for filmmaking: We need people to get together.

- ――At a commemorative event for the Japan Foundation Awards, you also wanted to have, and did have, a conversation with Nagata Kazuhiro, Director of the JT Biohistory Research Hall. You've published numerous such conversations in book form, and had conversations with people in so many different fields.

- It is so much better than talking alone. I make a point of never accepting invitations to give talks, but when the invitation is to have a conversation with someone, I figure, "Why not?", and make it a point to accept.

When you give a talk all by yourself, you only talk about the things you already know. But when you talk with someone, you realize things you weren't expecting or find yourself saying things you wouldn't have thought to say. It's not that I'm making it my life's work. It's just that the more I happened to run away from giving talks, the more chances I had to take part in conversations.

It's true that I have been chasing after people like Mr. Nagata, Mr. Fukuoka Shin-Ichi, and other scientists whose activities I'm curious about, but there aren't that many (such people).

- ――Do their ideas also come to life in your works?

- I'm not doing anything in particular to give them life. That said, in talking with Mr. Nagata about the idea of "omission" in tanka as a form of expression, or in talking with Mr. Fukuoka Shin-Ichi, I hear him say things like, "Our studies are not about the why, but about the how," or, "Our research is not about understanding why things are the way they are, but about understanding how it is they are the way they are," and I think that's what matters in film, too. It's interesting to think about how similar these things are, right?

You can't see why something is the way it is, so the most important thing when shooting is to observe how it is the way it is. Cameras can be a scary thing, indeed.

Japan Foundation Awards commemorative event "Butterflies and Cosmos: A Conversation between Koreeda Hirokazu and Nagata Kazuhiro"

Japan Foundation Awards commemorative event "Butterflies and Cosmos: A Conversation between Koreeda Hirokazu and Nagata Kazuhiro"- ──As a director, you seem to have continually fought against facile understanding, black-and-white assumptions about people, and over-simplification. How do you feel about making films today in an information society where information is disseminated by various media, and in an era when the world is increasingly segmented?

- Good question. I'd say that creating things, right now, is hard.

- ──Hard in what way?

- It's always hard, but today, you hear a lot of people talking about "expression that hurts no one." But expression can also turn into violence in a relationship, right? There's always a danger of that. Is there such a thing as expression that can never hurt someone? I'm not saying a creator should stop caring about it, but I do think that when you make something with the aim of not hurting anyone, what you get is something that really won't reach anyone, and creators need to be prepared for that in some way, on some level.

Of course, I also believe that what people expect of creators, be it in terms of ethics or knowledge, changes with the times, and we absolutely have to be sensitive to that.

It's been twenty-five years since I first started making films, and back then when I started, shooting on film was the norm, and if you didn't shoot on film, it wasn't a film. Nowadays, there are probably only a few people in all of Japan who shoot works for theatrical release on film. Things have changed way beyond anything we could have imagined. Even screenings using film are almost non-existent.

So, what does it even mean to shoot a work for theatrical release on film any more? That's not something I would have ever questioned twenty-five years ago, but now I can't help but wonder if there is any point to shooting on film. It's fair to ask why a film that doesn't open in a theater isn't a film, and if it's easier to create films without a theatrical release, then why wouldn't people start thinking that was better?

There are so many choices now that creators and audiences alike are forced to think in very simple terms about what a film is. I don't mean to say that that's a bad thing. I think it's something we should think more about. But, then, today's Japanese film industry isn't thinking about it at all. The people releasing films are mostly indifferent to it and have no solutions, and here I go complaining again. At this rate, I'm skeptical things are going to be okay.

- ──Movies take a lot of time to make and several hours to watch, but with the increasing speed of information processing, it feels like it is becoming more and more difficult to create in this medium.

- True, it has gotten harder to create, though it's not something I'm too worried about personally, if I'm being honest.

It doesn't suffice to say, "There is no such thing as expression that never hurts anyone." Before you put something out there, you have to think it over twice, three times. This isn't some new responsibility that emerged with the Internet. It began well before that, from back when I was involved in television. With television, which is something made for a mass audience, there have to be two or three layers of risk management, and the people who can manage that risk are the ones who should create.

Of course, now we live in an age when anyone can express themselves, so that's hard (laughs). It's hard, but then, the people expressing themselves have no training. That's why things "blow up." But I don't think there's much we can do about it. It's six one way, half a dozen the other.

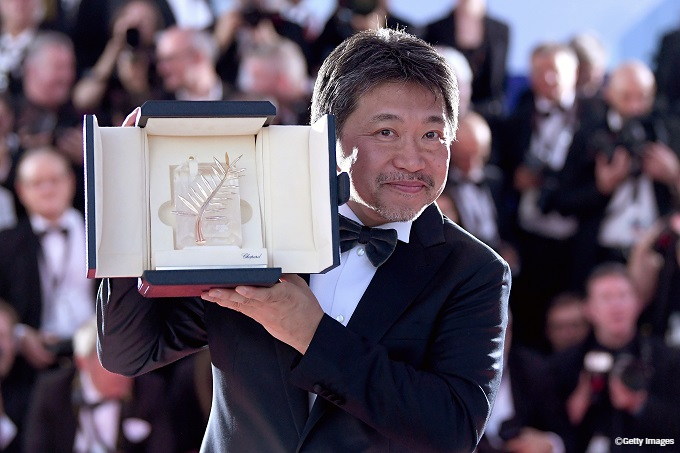

Shoplifters won the Palme d'Or, the top prize at the 71st Cannes Film Festival

Shoplifters won the Palme d'Or, the top prize at the 71st Cannes Film Festival- ──What we might call production ethics, or just consideration toward others, is also tied up with the "work style reform" movement, including efforts to train future generations through the production company BUN-BUKU, right?

- I shouldn't say anything too grandiose, and I don't want to talk about it, because my point isn't to simply "abolish power harassment." I've had my own share of being yelled at over and over, and there is virtually no one who gets yelled at and appreciates it (laughs). That kind of co-dependency is very common in filmmaking, and it's just unpleasant. So, for me, it's just a matter of trying not to do what was done to me, for one thing. It's not that big of a deal. It's just that I didn't like it, so I'm trying not to do it.

BUN-BUKU currently has 15 to 16 staff members, and 70 to 80% of the people working around me are women. I'm not really doing this to expand work opportunities for women, but I think it makes getting work done easier given my ego, and there is also the fact that out of the 200 or so people who applied, when I met with them, the best ones were all women. So, we have more women as a result, but not because I've been trying to prove something to society.

- ──It used to be that directors were seen as these top-down, charismatic figures who kept everyone under control, but it's not so easy nowadays, is it?

- If you've got the charisma, what's the problem (laughs)? But that's not going to last long, is it? Anyway, there are directors like that, and there are people willing to follow them, and there is not much point in criticizing them as such. When I hear someone is going to join a certain team, I just tell them not to (laughs). We still hear a lot about it in the film industry──sexual harassment and power harassment, that is.

- ──Looking ahead, are there new challenges you want to tackle or ideas you have for future projects?

- Not so much new challenges I want to tackle. However, there are so many things I want to do that I probably won't be able to do them all, not just movies. But the question is how much in the next ten years, and how to get it all done. I'd like to do dramas, and I'd also like to do theater.

Lead actor Yagira Yuya (left) won the Best Actor Award at the 57th Cannes Film Festival for Nobody Knows (photo courtesy of TV MAN UNION)

Lead actor Yagira Yuya (left) won the Best Actor Award at the 57th Cannes Film Festival for Nobody Knows (photo courtesy of TV MAN UNION)- ──Do you want to do overseas co-productions with lots of different countries?

- If I can. But it's not at all that I'm fed up with Japan and prefer overseas. There are some things you can understand across languages, but only if you have very strong interpreters, that's for sure. In both Korea and France, we were fortunate to have such people, and so we were able to get it done. It's not always that simple.

- ──It seems that there would be synergies as you resume working in Japan while taking advantage of your co-production experiences overseas.

- I'm sure that's true, no doubt. Even off-set it's important, but when you're the director and you're filming on set and you don't comprehend the language, you have to find ways other than language to understand each other, right? That means I have to give an okay not based on the meaning of the lines, but based on things that can't be verbalized──various nuances around the meaning, facial expressions, pauses, rhythm, the relationship between the camera and the actors, and so on.

In fact, those perceptions become even more important, and when I came back to Japan and was filming recently, I found myself noticing things other than words. "Huh? I've upgraded quite a bit," I thought (laughs). The feeling of sharpening my senses to something other than the meaning of the lines──you know, because I was filming in a country where I couldn't use the language, I felt like it activated a part of me that I'm not usually aware of, and that was interesting.

The experience of the two films (in France and Korea) has helped me realize──at last, at my age──that I can use that part of me, too.

- ──It's amazing that you can give an okay even when you don't understand the language of the lines.

- Well, of course, I'm not the only one involved in the decision, and I listen to the staff around me, but there is not really that big of a gap. It felt like there were plenty of things other than language for me to judge whether the current take was a good one.

- ──It seems like co-production is something that could help raise the general level of cinema in the world.

- Maybe (laughs). It's raised my own level, that's for sure.

- *¹ Asia Lounge: A conversation series led by Koreeda and other committee members, featuring discussions between leading Japanese filmmakers and filmmakers representing countries and regions around the world, including Asia.

https://2021.tiff-jp.net/en/

November 2021, online interview

Interview and text: Terae Hitomi (The Japan Foundation Communication Center, affiliation as of the time of the interview)

Related Articles

Related Events

Back Issues

- 2025.11.14 Stories from Both Si…

- 2025.10.24 Dialogue through Ani…

- 2025.6. 9 Creating a World Tog…

- 2024.10.25 My Life in Japan, Li…

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.5. 2 People-to-People Exc…

- 2024.5. 2 People-to-People Exc…

- 2023.12. 7 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2023.6.16 The 49th Japan Found…