The Significance of Reflecting on Japanese Contemporary Art in South Korea (Oh Jin-yee) / Seoul on My First Visit and at Present (Makoto Aida)

Oh Jin-yee, Makoto Aida

The Japan Foundation presented at the Museum of Art, Seoul National University, "Re: Quest--Japanese Contemporary Art since the 1970s," an exhibition surveying the art of the past four decades, between the 1970s and the present. The exhibition focused on the history of Japan's postwar art, which provided an important foundation for later work, and presented the survey of the last 40 years of Japanese contemporary art from various perspectives. It encompassed works dating after 1970 that have never been introduced in a comprehensive manner in Korea, and included works of important artists who remain highly influential in the field as well as those of younger artists. The following articles were contributed by Oh Jin-yee, senior curator at the Museum of Art, Seoul National University, and one of the exhibition's four Japanese and South Korean curators and by Makoto Aida, an artist featured in the exhibition who also gave a talk in Seoul.

The Significance of Reflecting on Japanese Contemporary Art in South Korea: Re: Quest--Japanese Contemporary Art since the 1970s

Oh Jin-yee

Senior Curator, Museum of Art, Seoul National University

"Re: Quest--Japanese Contemporary Art since the 1970s (hereafter abbreviated as "Re: Quest")," jointly organized by the Japan Foundation and the Museum of Art, Seoul National University, closed its doors in April 2013. As one of its curators, I feel that the exhibition's contents, and the timing and place at which it was staged, have provided several hints as to the significance of introducing art from a specific country in this era of globalization.

"Re: Quest" consisted of 112 works by 53 artists, all from the same time period and yet who had been rarely featured together even in their home country of Japan. It covered the movements in Japanese contemporary art over the past four decades, between the 1970s and the present, in a showcase organized from a historical point of view. Although this format itself is by no means new, the emphasis behind it is worth delving into further. That is, "Re: Quest" sought to trace the evolution in Japanese contemporary art that followed as a result of efforts to promote, critique, and develop it by none other than Japan's own society and art community. It was an experiment in giving significance and value to this art from the standpoint of a country in the same Asian region, without resorting to such misguided concepts as self-orientalism and exclusive nationalism, which commonly arise when analyzing Asian art from a Western perspective based on the European discipline of art history.

The timing of the exhibition, 2013, also helped to differentiate it from other shows of Japanese contemporary art. Up to now, major group exhibitions in the international art scene often spotlighted Japanese art from the late 1960s to early 1970s, mainly revolving around the works and influences of the Gutai group. In contrast, "Re: Quest" was able to make a bold departure from this convention and literally launch a re-quest for the four decades after the 1970s thanks to two elements. First and foremost, it came from the participation of the Japanese curators who injected a sense of unfiltered authenticity into the exhibition through their role in shaping Japan's art world during the featured period by sharing real-life experiences with the featured artists. Second, it was due to the fact that a sufficient amount of time had elapsed since the 1990s, when art critics went all out to define the characteristics of Japanese contemporary art with terms like Japanese neo-pop.

"Benefits" of introducing Japanese art in South Korea

On a different note about timing, South Korean journalists highlighted the fact that the exhibition coincided with the 40th anniversary of the establishment of the Japan Foundation. In other words, they viewed it as a program organized by a public institution dedicated to promoting Japanese culture overseas--a national strategy. This interpretation mirrors the general understanding Koreans have about cultural exchange between two countries, particularly their own and Japan. In fact, the history of Japanese contemporary art exhibitions in Korea is not all that long. A full-scale introduction of foreign cultures started only in the 1980s. This was before the censorship of Japanese media was lifted, so public opinion was divided over comprehensive exhibitions of art from Japan. The exhibitions continued, but only in the realm of friendly, neutral cultural exchange and on condition that Korea had equal opportunities to promote its culture in Japan. Then, the 1990s saw a rise in exhibitions that did not merely introduce foreign cultures but imported and presented them through Korea's unique perception.

Around this time, the trend at major Korean museums shifted to planning and organizing their own exhibitions of Japanese contemporary art. And more recently, under the slogan "cultural competitiveness," they have established the presumption that the next step in cultural exchange is to promote not only understanding and acceptance but also, and more importantly, exports with concrete benefits to the economy. This is still the mainstream in Korea today: we see cultural exchange through the quantitative notion that if Japanese culture is introduced in Korea, Korean culture should likewise be introduced in Japan; and we interpret art exhibitions planned and organized in Korea as a profit-making strategy. The journalistic coverage of "Re: Quest" confirmed it.

Favorable response of South Korean youths

By contrast, the response to the "Re: Quest" exhibition from visitors, particularly the younger generation, suggested a new willingness to accept foreign cultures. Youths who attended the exhibition tour guided by museum staff showed their interests in the pure diversity of the works, rather than in the grounds for displaying Japanese contemporary art in a Korean national museum or the secret strategies that might lie behind the exhibition's contents. This can be said that their response followed a very basic purpose of art exhibitions, which is to share wonderful art pieces with people beyond artists. But holding Japanese art exhibitions in South Korea did not quite start with the basics and so it might be appropriate to say that the "Re: Quest" exhibition rather went back to the basics after a long detour. The great interest in the works and in the individual artists resulted in the success of the three artist-talk events. Reservations closed a month in advance. And visitors in the 20s and 30s had so many questions that not all could be answered before the allotted time passed and the events came to a reluctant end. A good number of the questions went further than simple requests for information. The visitors first expressed their views, and then sought the artists' responses. The talks, I believe, provided a tremendous opportunity for both artists and audience to share their challenges based in a sense of mutual sympathy that comes from the fact that they are living at the same moment in time.

The number-one response to the Japan Foundation's questionnaire about ideal exhibition themes in future was Japan's emerging young artists. Korean art lovers and Japanese artists are on the same wavelength and share the similar outlook on life. Being able to realize that firsthand was the best reward I received from "Re: Quest," and these points are the very reason I believe in giving contemporary art its own unique place in art exhibitions, and setting it apart from "older" art.

Oh Jin-yee

Oh Jin-yee

As senior curator at the Museum of Art, Seoul National University, Oh specializes in Asian modern and contemporary art history and has organized exhibitions such as "Document Culture: Tradition and Present" (2009), "The Portrait of Korean War" (2010), and "Korean Art in Textbooks" (2012).

In "Re: Quest --Japanese Contemporary Art since the 1970s," she served as curator along with Tohru Matsumoto, deputy director of the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo; Masahiko Haito, a curator of Aichi Triennale 2013; and Yukie Kamiya, chief curator at the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art.

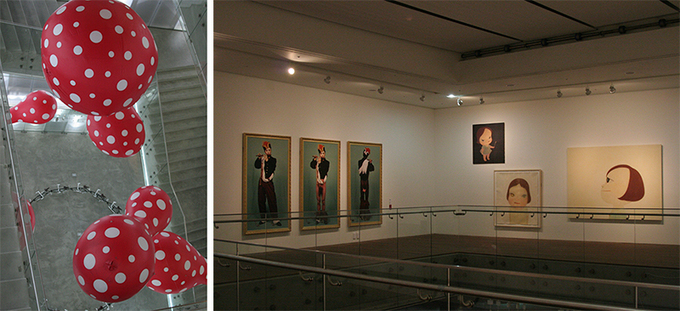

Installation view at the Museum of Art, Seoul National University

Exterior of the Museum of Art, Seoul National University

Guidepost to the New Space, Yayoi Kusama, 2013

Installation view at the Museum of Art, Seoul National University

Seoul on My First Visit and at Present

I've lost count of my visits to South Korea. The latest trip marked the seventh, I think. Seoul outnumbers any other city in the world as a destination for my overseas travels (although I might have stayed longer in New York, where I lived for six months). It's quite an amazing track record for someone like me who doesn't do a whole lot of traveling abroad to begin with. I guess it might come from my personal characteristics, but it's probably even more an inevitable given for a Japanese artist who launched his career in the early 1990s.

My first visit was in 1992. I had just graduated from an art university, having no real opportunity to unveil my work, and so I was doing part-time jobs and feeling blue. And that was when a friend of mine, Tsuyoshi Ozawa, invited me to come along on his trip to Seoul. Some elder friends of his were holding a two-person exhibition. Let's see the exhibit, he said, and have a good time. The artists were Takashi Murakami and Masato Nakamura. I had seen one solo exhibition by Murakami, and never heard of Nakamura. Both were on the verge of making a big break and still relatively unknown in the world of art.

This being only my second trip abroad, everything about it felt fresh and exciting. The exhibition, titled "Nakamura and Murakami," turned out to be a self-funded, self-organized event. The venue wasn't a fancy gallery at all but rather a nightclub-like space frequented by youths. The one thing about the event that remains vivid in memory is the opening party, a wild affair starring Epaksa, who was a small cult figure in Japan. His pioneering rendition of ponchak music (it struck me as a super-uptempo, techno version of the Japanese enka) enveloped the crowd in a bizarre frenzy.

Nakamura was then a rare case being an international student at an art university in Korea. He acted as our tour guide of sorts, and introduced us to then emerging Korean artists. A number of them have grown to be prominent figures in the art scene today, although I'm rather forgetful and can't seem to remember exactly who I met on this particular trip. What I do remember is seeing some of their work and sensing instantly that these artists were shooting for goals very similar to ours (that is, the Japanese artists there who had yet to make a break). Even now, I feel there's a strong affinity between Japanese and Korean artists who debuted in the early 1990s and whose work gravitates toward pop art.

The ban on imports of Japanese popular culture was still basically in place in Korea. But by this time, tiny shops on the street corner secretly dealt in Japanese music and manga, and they were beginning to gain a following. Similarly, Korean culture had a presence in Japan, although we couldn't access products as openly or effortlessly at any shop wherever as we can today. Back then, Japan and Korea were "close but distant" neighbors. And while I enjoyed the exotic atmosphere of my first trip to Korea, there was also a certain tension about being a Japanese tourist.

All the same, I was a young tourist with a healthy curiosity. Before the trip, I read an introductory guide to Korean history and studied up on Inuhiko Yomota's theory of Korean culture. And after arriving, I asked people all kinds of questions. I had much to learn especially from a young man--I don't recall his name--who was a volunteer interpreter for the "Nakamura and Murakami" exhibition and offered us a place to stay for a few nights. He was a third-generation Korean living in Japan, and attending Korean university at the time as an international student. This man told me all about the real-life experiences that came with his complex identity of having two home countries.

What I absorbed during this trip later culminated in Beautiful Flag (War Picture Returns) depicting two girls carrying their national flags: the Japanese girl, a Hinomaru, and the Korean girl, a Taegukgi. I forget what inspired me to base the image of the Korean girl on Yu Gwan-sun. I may have seen a relief in some park in Seoul of the anti-Japanese activist who perished in prison. Though tremendously simple in concept, this painting was one of my early works, created out of my intense first impression on the trip. And for that, I'm still fond of it today.

Having co-hosted the soccer World Cup in 2002, Japan and Korea are now on a steady path to becoming "close and close" neighbors. Lately when I walk down the streets of Seoul, time and again I fall under the illusion that I'm in Tokyo. Sometimes I wonder if age has numbed my sensibility. But it can't be just me. On the last trip, too many eateries around Myeong-dong had signs posted on their doors--"Featured on Japanese TV!"--in the Japanese language no less. All this visitor-friendliness does spoil the fun of traveling abroad to some extent. By contrast, the news suggests there is animosity between Japanese and Koreans. Personally, I take this as a by-product of relations that have grown so close over such a short period of time.

Such was the state of affairs when "Re: Quest--Japanese Contemporary Art since the 1970s" presented a comprehensive survey of Japanese contemporary art, featuring everything from the Mono-ha artists of the 1970s to up-and-coming talent. I hear the exhibition drew a record number of visitors to the Museum of Art, Seoul National University, and am simply glad about this marvelous news. It's certainly important to introduce traditional culture that is an obvious source of pride to the originating nation. At the same time, I feel that this exhibition has done something exceptionally meaningful by introducing a new culture in the making, whose full significance is yet to be established, and by promoting it with success. The benefits this will have on the understanding and friendship between Japan and South Korea is immeasurable. I thank also the many Korean youths who came to my talk session and gave me such a warm welcome and made me feel comfortable.

Makoto Aida

Makoto Aida

Born 1965 in Niigata Prefecture. Aida earned an MFA in painting at Tokyo University of the Arts (former name: Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music), in 1991. He has participated in numerous exhibitions in Japan and abroad, centering on solo exhibitions at the Mizuma Art Gallery in Tokyo. Major recent showcases include "Bye Bye Kitty!!!--Between Heaven and Hell in Contemporary Japanese Art" (Japan Society, New York, USA, 2011), the First Kiev International Biennale of Contemporary Art (Mystetskyi Arsenal, Kiev, Ukraine, 2012), and "Aida Makoto: Monument for Nothing" (Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, Japan, 2012). He is currently showing as a member of The Group 1965 at the Setouchi Triennale 2013.

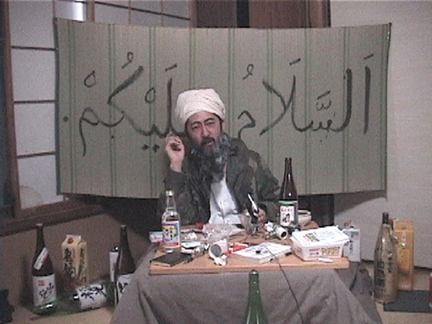

The Video of a Man Calling Himself Bin Laden Staying in Japan, 2005

Video (8 min. 14 sec.)

© AIDA Makoto

Courtesy Mizuma Art Gallery

Beautiful Flag (War Picture Returns), 1995

a pair of two-panel folding screens / fusuma (sliding door), hinges, charcoal, self-made paint with Japanese glue, acrylic

Photography Kei Miyajima

© AIDA Makoto

Courtesy Mizuma Art Gallery

Makoto Aida talk session at "Re: Quest--Japanese Contemporary Art since the 1970s"

(April 13, 2013, Museum of Art, Seoul National University)

Keywords

- Anime/Manga

- Arts/Contemporary Arts

- Music

- Education/Children

- International Exhibition

- Cultural Diversity

- Japanese Studies

- Transboundary/Study Abroad/Travel

- Republic of Korea

- Japan

- Seoul National University Museum of Art

- Contemporary art

- Art history

- Self-orientalism

- Exclusive nationalism

- Japanese neo-pop

- Seoul

- Takashi Murakami

- Masato Nakamura

- Ponchak

- Epaksa

- Inuhiko Yomota

- Yu Gwan-sun

- World Cup

- Tokyo

Back Issues

- 2023.12. 7 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2023.6.16 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2023.4.24 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2022.12.27 Living Together with…

- 2022.12.27 Living Together with…

- 2022.8.12 Inner Diversity <…

- 2022.3.31 The 48th Japan Found…

- 2022.3.29 Beyond Disasters - T…

- 2021.11.29 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2021.4.13 Crossing Borders, En…