Dialogue between Sankai Juku Artistic Director Ushio Amagatsu and Theater Critic Tamotsu Watanabe: From Japanese Dance

Ushio Amagatsu, Artistic Director of Sankai Juku

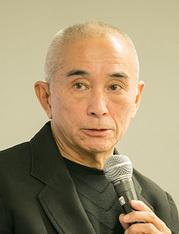

Tamotsu Watanabe, Theater Critic

2013 Presentation Ceremony for the Japan Foundation Awards

The Japan Foundation presented the Japan Foundation Award 2013 to Sankai Juku, and hosted a commemorative event for the dialogue between butoh dancer Ushio Amagatsu, Artistic Director of Sankai Juku, and theater critic Tamotsu Watanabe. Many people came to the event's venue, the Japan Foundation JFIC Hall, for this rare occasion presenting an insight into Ushio Amagatsu's thoughts on dance.

Behind the scenes

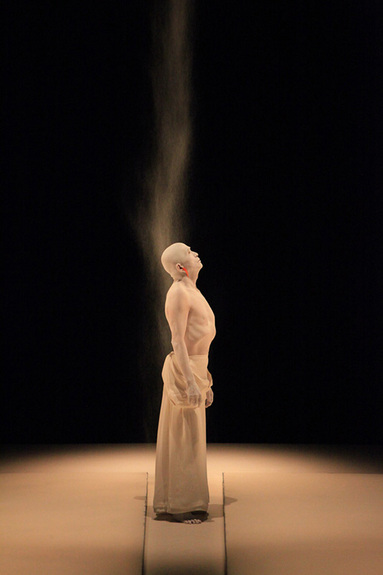

AMAGATSU: (After watching a digest version of two Sankai Juku performances UMUSUNA: Memories before history and TOBARI: As if in an inexhaustible flux at the venue) Firstly, the word umusuna in the title - a similar word would be ubusuna - is an old word meaning "the place you were born." The word primarily refers to a small area, but if you take a broader, universal, planet-wide perspective, I think it's possible to imagine lots of places where humans were born on Earth. So, I created this piece to express the places where humans have a connection with nature, comprised of the elements of earth, water, fire, and air, and to also bring time into the mix. On stage, the sand continues to fall from the very beginning of the performance. As the sand falls, it piles up, as if to symbolize time. I've also used sand for the previous work titled UNETSU: The egg stands out of curiosity, and in that piece, we have single strands of water and sand falling, with the sand making a pile and the water creating a horizon. It was an attempt to create a place where the beginning and end of life coexist. But in UMUSUNA, the sand continues to fall in the center of the stage to show life as a vertical line, something that does not disappear, but accumulates and so makes you sense the time passing by. The stage is divided at the center into two sides, and the sand is spread over the floor on stage left and stage right, encompassing the four elements (fire, water, air, and earth) represented by colored light.

UMUSUNA: Memories before history (C) Sankai Juku

WATANABE: What material is used for that stage?

AMAGATSU: Usually, we prepare a layer on top of the surface of the theater stage to dance on. For this time, the top layer is made of linoleum, a material often used for dance performances. We then spread an even layer of sand on top of that. As the dancers move, the sand is scraped away, and so, an hour and a half later, we get a relief on the surface engraved by the dancers' movement. You don't usually get to see the dancer's energy after an hour and a half just by looking at the floor, but here you can. So, I like the idea of stage art that changes with time. That's why I use things like sand or water that bring tangible qualities into my work.

WATANABE: What about TOBARI?

AMAGATSU: There is an oval shape in the middle of the stage lit with stars. These stars are actually 2,200 LED lights and accurately represent the constellations you see in August in Japan. There are also 6,600 stars on the backdrop of the stage, and these are also August constellations centered on the North Star. It's actually a black screen with holes of different sizes to represent the different brightness of the stars. These props are all made by the dancers themselves. The dancers create the props and artwork for the stage while they practice for their performance. In that way, they can really immerse themselves into the piece from the very beginning. The dancers do not simply fit themselves into a created environment at the theater, but know the space very well and exist within it. This hands-on approach of being involved from the first stages of creation results in adding various elements to the dancers' preparation of the piece. This is what has remained unchanged since Sankai Juku first started.

TOBARI: As if in an inexhaustible flux (C) Sankai Juku

WATANABE: Now, the word tobari can simply be explained as "curtain," but how do you connect TOBARI's theme with stars?

AMAGATSU: Tobari itself is an ancient word, referring to the sheer fabrics that were used as partitions, but it then took on the meaning of the line separating day and night. In Japanese we have the phrase yoru no tobari ga oriru ("the tobari of night falls"; meaning "the night falls"), but the line between day and night is ambiguous. When we say "it's night," night has already fallen, in the past tense. Meanwhile, the starlight we see now is starlight of long ago. It is light that shone several hundred million or tens of thousands years ago, not of this time. These ideas inspired me to create Tobari, questioning whether or not the present is really the present, and expressing the acceptance of the past as the present.

WATANABE: Your work, and not just these two pieces, tends to be based on cosmic or philosophical thought, but where does this come from?

AMAGATSU: When I look back, I think my first tour to Europe in 1980 was the biggest turning point for me.

Life

WATANABE: What brought you to Europe?

AMAGATSU: The French Embassy's cultural counselor had seen an 8-mm video of my performance, and so, I was invited to the embassy. Then, the counselor made a phone call to France and booked us performances at Le Forum des Halles and Carre Silvia-Monfort in Paris then and there right in front of my eyes. So, we went to Paris, and while we were performing there, the program director of the Nancy International Festival heard of us and came to see our performance, and signed us up. Then, we went to the Nancy International Festival, and since we performed for the final program on the last day of the festival, many people came to see us. At the press conference we held then, I said we wouldn't be returning to Japan for a year and that we would keep performing and spending time in Europe.

WATANABE: Did you say that without having any specific plans?

AMAGATSU: At the time, we were only scheduled to perform in three places including the Nancy Festival. But with the support from various people, it became an amazing year. We were invited to the Avignon Festival and the Sigma Festival in Bordeaux, and then we had more and more bookings for regional areas in France, and then Switzerland, and then Italy. It was certainly like a thrilling adventure, and thanks to the help of many people, we managed to finish our year with the performance at the Cervantino Festival in Mexico.

WATANABE: That must have been a pivotal experience for you.

AMAGATSU: We spent every day, being showered by different languages, food, and lifestyles, and I felt that these differences all came from those of cultures. But then again, we also had the opportunity to actually see the primitive wall paintings of Lascaux or the megalithic structures across Europe, and I thought that all cultures have a similar impulse to create forms and paintings, and that there was a universality that was born from nature. Looking back, I feel that these ideas of difference and universality have helped me along.

WATANABE: Your butoh dance pieces always seem to be in pursuit of the human existence in nature or how humans relate to the universe.

AMAGATSU: The individual is an existence that has a beginning and an end. Although the individual itself is discontinuous, outside your body there is a continuity that flows like a river. In other words, it is discontinuity enveloped in continuity. So, we have both elements within us, and I hope to express the idea of eternity as a core theme of my entire work.

WATANABE: Dance can be described as a transient art form because it only lasts for a second on stage, and so eternity and transience are major elements in dance. I think that you have reached your theme through these experiences and that turning point.

AMAGATSU: The fact that I grew up near the sea may also have had something to do with it. The passage from Rimbaud's Une Saison en Enfer (A Season in Hell) "Elle est retrouvée, Quoi ? -- L'Éternité. C'est la mer allée, Avec le soleil. (It is found again. What? Eternity. It is the sea. Gone with the sun.)" speaks to me. It felt like it was describing the same sort of scenery I've seen in my mind ever since I was a child.

Plans for the future

WATANABE: What kind of pieces do you hope to create in the future?

AMAGATSU: I hope to express pretty much the same theme in the same sort of rhythm but maybe from different angles, or I might simply express things I want to see. I keep notes of the things that catch my attention or questions I have in daily life, and the notes that remain even after a time eventually build up to become a piece. I don't take the approach of starting off with a specific title or trying for a different theme.

What is Japanese dance?

WATANABE: In Japan, dancers are deemed to be more proficient as they become older; so, the older they are the better. On the other hand in terms of European modern dance or classical ballet, for example, older dancers are not appreciated that much. In that sense, your dance is rooted in an extremely Japanese sensibility. So, I believe you'll be performing even when you're 100 years old like Kazuo Ohno. I'm certain that you'll go on to discover art of old age.

AMAGATSU: I choreograph my own work and perform the pieces myself. So, I accept the fact that I am getting older and create dance pieces with moves that suit my age. I can't choreograph moves for myself that I'm not capable of doing. In other countries, they describe dance as athletic ability, but in Japan I believe it's not about athletics but oscillation. It's about our relation with space or time.

WATANABE: In Europe, dance is basically about the visible body, while in Japan it's based on the invisible body. That is to say, we have different views regarding the body.

AMAGATSU: I agree. I like the idea of the "voice of the body" in your book Nihon no buyo. For details, please read Mr. Watanabe's book Nihon no buyo (Dance in Japan) (Iwanami Shinsho). It's a wonderful read!

WATANABE: Thank you for mentioning my book, and that's it for our dialogue.

Q&A session

Q: Does the Sankai Juku always consist of the same members?

AMAGATSU: There is one member who's been with us since the start. He's in his 38th year. We also still have a few members who went with us on our first tour to France. The dance troupe members were fixed at first, but the average age just went up and up! So, we started having younger members join us too. Now, our youngest members are in their twenties and the others are from their thirties to sixties.

Q: What were your thoughts on getting involved with opera performances? With opera, the creativity starts with other people, and I think that that's a little different from your usual dance performances where you are involved from the first stages of creation.

AMAGATSU: This may sound odd, but I saw it as an opportunity to rediscover the work I should be doing. My work in opera was based on the attempt to reflect my dance style in a different genre.

Q: Why do you paint yourselves white?

AMAGATSU: White paint is something that has existed before I started butoh dancing, and it's not something unique to Japan. White paint is used in festivals and on ceremonial occasions in various cultures, and I believe that's why it allows us to share a universal image. Perhaps it represents something like an entrance from the ordinary to extraordinary. I also see it as a tool to erase individuality. Head shaving, for example, is a similar attempt to do away with individual characteristics, in this case, hairstyles, and I think the white paint helps remove bodily features, emphasizing the fact that the dancers are merely human beings. The white paint also shows different expressions according to the light, and that's another interesting aspect for me.

Q: I'd like to ask how you choose the costumes, and why you always have blood running from your ears?

AMAGATSU: The blood from the ears is something to give us courage. It expresses the deadline for the body, and it's the last bit of makeup we apply, enabling us to concentrate on our performance. Regarding the costumes, in ancient Greece and Rome, people wore togas, wrapping cloth around them. It's the same with the Japanese kimono. In other words, I try to have costumes that are unisex or universal, before the world was divided into trousers and skirts. Since Sankai Juku is a troupe of men only, we also hope to include the feminine essence through these costumes. Trousers were invented to ride horses, weren't they. So, I want to have clothes from the stage before they acquired characteristics like that.

(Photos by Sayako Kakushin)

Ushio Amagatsu

Ushio Amagatsu

Ushio Amagatsu was born in Yokosuka City, Kanagawa Prefecture, in 1949 and founded the butoh dance troupe Sankai Juku in 1975. He created Amagatsu Sho (1977), Kinkan Shonen (1978), and Sholiba (1979), before embarking on his first world tour in 1980. Since 1982, he has been based in the Theatre de la Ville, Paris for his work and has created 14 joint productions so far. He also started directing opera in 1997, and his production of the Bartok opera Bluebeard's Castle conducted by Peter Eötvös was performed at the Tokyo International Forum. He also directed Peter Eötvös' opera Three Sisters (based on the play by Anton Chekhov) at the Opera National de Lyon in France in 1998, and this won the Prix du Syndicat National de la Critique, France. He teamed up with Peter Eötvös again in March 2008 for his new opera Lady SARASHINA (based on Sarashina Nikki written by the daughter of Sugawara no Takasue). This had its world premiere at the Opera National de Lyon and was also awarded the Prix du Syndicat National de la Critique, France.

Official website: http://www.sankaijuku.com/

Tamotsu Watanabe

Tamotsu Watanabe

Tamotsu Watanabe is a theater critic born in 1936 in Tokyo. After graduating from Faculty of Economics, Keio University, he joined the film, theater production, and distribution company Toho. He debuted in 1965 as a critic with Kabuki ni joyu wo (Have actresses in Kabuki). After serving as the chief of planning, he left the company. Ever since, he has won the Agency for Cultural Affairs' best newcomer award for art with Onnagta no unmei (Destiny of actors of female roles), Kawatake Award for Haiyu no unmei (Destiny of actors), Hirabayashi Taiko Award and Kawatake Award for Chushingura, mo hitotsu no rekishi kankaku (Chushingura, another sense of history), Yomiuri Prize for Musume dojoji (The maiden at Dojo-ji Temple), Minister of education art award for Yondaime ichikawa danjuro (Ichikawa Danjuro IV), Yoshida Hidekazu Award for Showa no meijin toyotake yamashirono shojo (The Master in the Showa Period: Toyotake Yamashirono Shojo), and Yomiuri Prize for Mokuami no meiji ishin (Mokuami's Meiji Restoration). His book recommended by Ushio Amagatsu during the talk event is Nihon no buyo (Dance in Japan) (Iwanami Shinsho).

Official website: http://homepage1.nifty.com/tamotu/

Keywords

- Dance

- Theater

- Arts/Contemporary Arts

- Performing Arts

- Music

- Philosophy/Religion

- The Japan Foundation Awards

- Japan

- Mexico

- Italy

- Switzerland

- France

- Sankai Juku

- Butoh

- Paris

- Le Forum des Halles

- Carre Silvia-Monfort

- Nancy International Festival

- Avignon Festival

- Bordeaux

- Sigma Festival

- Cervantino Festival

- Lascaux

- Megalithic culture

- Rimbaud

- Modern dance

- Classical ballet

- Kazuo Ohno

Back Issues

- 2025.7.31 HERALBONY's Bold Mis…

- 2024.10.25 From Study Abroad in…

- 2024.5. 2 People-to-People Exc…

- 2022.11. 1 Inner Diversity<3> <…

- 2022.9. 5 Report on the India-…

- 2022.6.24 The 48th Japan Found…

- 2022.6. 7 Beyond Disasters - …

- 2021.3.10 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2020.7.17 A Millennium of Japa…

- 2020.3.23 A Historian Interpre…