"Home-for-All" in Rikuzentakata, and the Venice Biennale International Architecture Exhibition

Toyo Ito, Kumiko Inui, Sou Fujimoto, Akihisa Hirata (Architects), and Naoya Hatakeyama (Photographer)

Every two years in Italy, the Japan Foundation presents the Japan Pavilion as a national participant in the Venice Biennale International Architecture Exhibition.

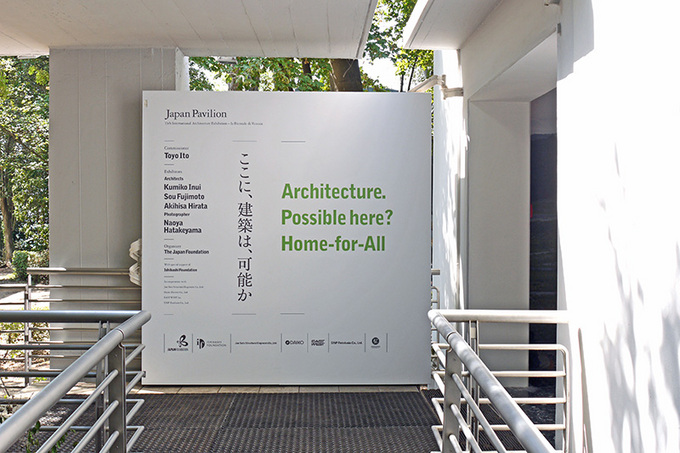

Signboard of the Japan Pavilion (Photo: Naoya Hatakeyama)

Exhibit of the Japan Pavilion (Photo: Naoya Hatakeyama)

For the 13th International Architecture Exhibition at the Venice Biennale, the Japan Foundation invited as commissioner the architect Toyo Ito, and as exhibitors, architects Kumiko Inui, Sou Fujimoto, and Akihisa Hirata, and photographer Naoya Hatakeyama.

From left: Kumiko Inui, Toyo Ito, Akihisa Hirata, Sou Fujimoto, and Naoya Hatakeyama

Under the theme "Architecture. Possible here?" the Japan Pavilion showcased the designing and building process of a "Home-for-All" in the city of Rikuzentakata, Iwate Prefecture, being expected to serve as a little breathing place for victims of the devastating Great East Japan Earthquake. For its endeavor to explore the most primal themes--that of re-examining the modern value of 'originality' in architecture, and why and for whom a building is made--the Japan Pavilion won the exhibition's highest honor, the Golden Lion for Best National Participation.

The Japan Pavilion wins the Golden Lion for Best National Participation in the 13th International Architecture Exhibition at the Venice Biennale (Photo: Naoya Hatakeyama)

This article covers the report titled "Architecture After 3.11" co-organized by the Architectural Institute of Japan and held at the University of Tokyo's Fukutake Hall on September 25.

Building the "Home-for-All" in Rikuzentakata

ITO: I thank all of you joining us here today. It's been a month and a half since the last report on August 5, before we left for Venice. I never dreamed we would bring home the Golden Lion... No, that isn't entirely true. I flew out fully expecting to win this prize. But first, let me share with you the idea behind the Japan Pavilion exhibit.

ITO: I thank all of you joining us here today. It's been a month and a half since the last report on August 5, before we left for Venice. I never dreamed we would bring home the Golden Lion... No, that isn't entirely true. I flew out fully expecting to win this prize. But first, let me share with you the idea behind the Japan Pavilion exhibit.

I presented my proposal "Architecture. Possible here?" in late July 2011, when the Japan Foundation made an open call for commissioner of the Japan Pavilion. Around the same time, I was also engaged in a project of my own called "Home-for-All," which seeks to provide gathering places for people who had lost their homes in the Great East Japan Earthquake. I completed the first "Home-for-All" in October last year (2011), in the Miyagino Ward of Sendai City, Miyagi Prefecture, and the Japan Pavilion is an extension of this project.

Whereas I alone designed the Miyagino "Home-for-All," I assembled a design team comprising Kumiko Inui, Sou Fujimoto, and Akihisa Hirata for this time. I also asked Naoya Hatakeyama to participate in the project, not only as a photographer but also as a contributor being involved from the early stages of concept development. Mr. Hatakeyama is a native of Rikuzentakata, and in fact, it was his photographs of the city taken immediately after the quake and tsunami that inspired and led us to build the Rikuzentakata "Home-for-All".

Imaizumi area of Kesencho, Rikuzentakaka. April 4, 2011 (Photo: Naoya Hatakeyama)

To tell the truth, I didn't intend to build a "Home-for-All" in Rikuzentakata at first. Initially, I envisioned making an actual architecture in the courtyard of the Japan Pavilion, and then after the Venice Biennale, relocating it to the disaster-stricken city as a gift. But this didn't fit in with the grand plan. Transporting the building after the exhibition's closing in late November means its completion in Japan would be the following spring, at the earliest. That was too late. Besides, I didn't want to make a building primarily for display. So in the end, we prepared two structures simultaneously: one in Venice, as an exhibit, and the other in Rikuzentakata, for real.

Encounter with Mikiko Sugawara--a key figure in the project

The idea started to take concrete shape on November 26, 2011, when all of the team members visited Rikuzentakata together. There, we met Mikiko Sugawara. Despite having lost her mother and elder sister in the disaster, this woman was dedicating herself to a multitude of activities supporting her new community and its residents. Inspired by her energetic spark, we decided to build a "Home-for-All" on the grounds of her temporary housing site. And after returning to Tokyo, we held several meetings discussing how best to incorporate architecture into this site. Mr. Hatakeyama participated in these meetings, contributing a great deal through his perspective as a photographer.

The city of Rikuzentakata in November 2011

Our discussions in Tokyo, however, made next to no progress. I had always anticipated it would be difficult to sum up one idea together with several different architects, who each have a strong personality. But the reality was beyond my imagination. And just as I was contemplating returning to Rikuzentakata and rethinking the plan altogether, Ms. Sugawara called, saying that she had found a perfect site, and wanted to take us there. The site was symbolic--a vast plain at the foot of the mountain where the tsunami had washed away everything, an empty flatland that commanded a clear view all the way to the ocean.

(Left) Meeting at Toyo Ito & Associates, Architects in December 2011

(Right) Finding the site on January 26, 2012

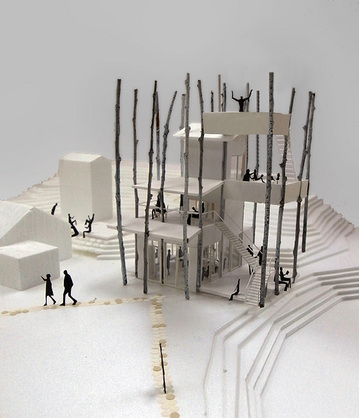

After the finding of this symbolic site, the project made a remarkable progress. The team members gradually developed common goals. For one, we wanted a vertical structure, like a fire tower, overlooking the entire city of Rikuzentakata. For another, we wanted the building to resemble a grove, making use of Japanese cedar salt-damaged by the tsunami. Even outside Rikuzentakata, I've seen many trees of Japanese cedar or pine at the foot of a mountain that were destroyed by the tsunami. But logs of withered cedar or pine are actually perfectly safe to use as building material. This idea was in part inspired by a remark from Mr. Hatakeyama, commenting that the design model would somehow remind Rikuzentakata locals of floats run at the July 7 kenka tanabata (star) festival. In May this year, we presented our final design to Ms. Sugawara and the other residents, and it was decided that the Rikuzentakata "Home-for-All" would consist of several individual spaces arranged in levels.

Model proposed on February 26, 2012

(Left) Logs of Japanese cedar near the site on April 12, 2012--these are later used as timber for the Rikuzentakata "Home-for-All"

(Right) Local residents and volunteers debarking the logs on May 19, 2012

Pillars made of Japanese cedar from Rikuzentakata at the Japan Pavilion

Meanwhile, construction of the Japan Pavilion was underway in Venice, overseen mainly by Mr. Hirata and his team. We decided to install symbolic pillars made of Japanese cedar from Rikuzentakata going from ground through ceiling, and also to process logs picked up near the venue to make pedestals for the study models. And to complete the exhibit, we paneled the walls with a 4.5-meter high, 60-meter long panoramic image of post-disaster Rikuzentakata, taken by Mr. Hatakeyama. I imagine shooting the scene must have taken a great deal of resolve, as Mr. Hatakeyama said he had never taken photographs of the kind before. In the end, he picked up a high-performance digital camera especially for the project, and captured some wonderful shots. The photographs were taken in late June this year (2012), when much of the debris had been cleared away and the bare land showed signs of its first patches of green. Although the image might look like any ordinary landscape at a first glance, I feel it embodies a myriad of Mr. Hatakeyama's emotions.

4.5-meter high, 60-meter long panoramic image of post-disaster Rikuzentakata, taken by Naoya Hatakeyama, covering the walls of the Japan Pavilion (Photo: Naoya Hatakeyama)

The complexity in the collaboration between architects

INUI: When I was invited to join this "Home-for-All" project, my initial reaction was hesitation for two reasons. One, I had reservation about making a new building in a disaster-stricken area. And two, I felt somewhat uncomfortable about collaborating with other architects to make that building. This second concern wasn't completely unfounded, either. In the beginning, the three of us had totally different ideas.

INUI: When I was invited to join this "Home-for-All" project, my initial reaction was hesitation for two reasons. One, I had reservation about making a new building in a disaster-stricken area. And two, I felt somewhat uncomfortable about collaborating with other architects to make that building. This second concern wasn't completely unfounded, either. In the beginning, the three of us had totally different ideas.

But the situation changed once we saw the new site Ms. Sugawara had found for us. After Ms. Sugawara lost her home in the tsunami, she evacuated to Rikuzentakata First Municipal Junior High School, just a short way up from the new "Home-for-All" site. Living under the same roof, I heard, formed a close-knit community of the group of evacuees. And now that they had moved out of the school and into temporary housing, she was worried that the precious community might fall apart. So she wanted a place that would help to sustain the community ties, even after individual members had started a new life. This story inspired each of us to form a common vision. That is, through architecture, we wanted to play a role in sustaining this community born of extraordinary circumstances.

There's a term for a sense of solidarity often evoked in evacuation sites after a natural catastrophe--"disaster utopia." I imagine the situation occurred in Ms. Sugawara's community was a kind of "'disaster utopia." The problem is, these communities are inevitably short-lived. Hence, the members long for a gathering place to preserve their ties. This place needs to be not only functional but also symbolic. If it's a building, for instance, the building should embody some symbolic quality that brings shared memories back to life.

Dealing with symbolism isn't exactly my area of expertise, as I'm not the type of architect with a prolific vocabulary of styles. But working with Mr. Fujimoto and Mr. Hirata--two architects different from each other, and from me--has helped me to tackle what I felt was my weak area. And this was an invaluable experience.

Catching a glimpse of the true nature of architecture

FUJIMOTO: When the exhibit in Venice was almost complete, I looked back on the project as a whole and thought, if I may say so myself, we had made an amazing display. The Venice exhibit showcases the process of designing the Rikuzentakata "Home-for-All," but this process was by no means simple. It led us to the all-important question "what is architecture?" and it reflects each of our personal exchanges with Ms. Sugawara. And with Mr. Hatakeyama's photographs of pre- and post-disaster Rikuzentakata, the exhibit even represents multiple layers of time--the past, the present, and the future. The Japan Pavilion in fact contains the various elements of a city, in its juxtaposition of the concrete with the abstract, the individual with the society, the building with the community as a whole. The elements involved in making a single building are manifold. I think this is what architecture is really about.

FUJIMOTO: When the exhibit in Venice was almost complete, I looked back on the project as a whole and thought, if I may say so myself, we had made an amazing display. The Venice exhibit showcases the process of designing the Rikuzentakata "Home-for-All," but this process was by no means simple. It led us to the all-important question "what is architecture?" and it reflects each of our personal exchanges with Ms. Sugawara. And with Mr. Hatakeyama's photographs of pre- and post-disaster Rikuzentakata, the exhibit even represents multiple layers of time--the past, the present, and the future. The Japan Pavilion in fact contains the various elements of a city, in its juxtaposition of the concrete with the abstract, the individual with the society, the building with the community as a whole. The elements involved in making a single building are manifold. I think this is what architecture is really about.

All in all, the project offered us the curious experience of witnessing a building to take shape on its own. The distinct pillar structure of the Rikuzentakata "Home-for-All," for instance, was already there in Mr. Hirata's first model. The actual material was inspired by the story about the groves of Japanese cedar destroyed by the tsunami, and about the floats used in the local tanabata festival. All these different elements came together and gave the building tangible form.

Before the project kicked off, I was as uncertain about it as Ms. Inui was. I wasn't sure I was prepared to think about architecture after the Great East Japan Earthquake. But at a certain point, I realized that 'architecture' was there in Rikuzentakata, as it always has been. I will never forget that moment when the fog in my mind cleared and I caught a glimpse of the true nature of architecture.

Architecture that restores ties between people

HIRATA: Like Ms. Inui and Mr. Fujimoto, I also gave some thought to the significance of making a building in the devastated area, and to the complexities of collaborating with other architects. Also, as I became independent after working at Mr. Ito's office, I was worried I might end up serving as a liaison between the commissioner and exhibitors. So, I was determined to hold my ground and raise my own questions in the course of this collaboration project.

HIRATA: Like Ms. Inui and Mr. Fujimoto, I also gave some thought to the significance of making a building in the devastated area, and to the complexities of collaborating with other architects. Also, as I became independent after working at Mr. Ito's office, I was worried I might end up serving as a liaison between the commissioner and exhibitors. So, I was determined to hold my ground and raise my own questions in the course of this collaboration project.

But looking back now, I realize my pretentiousness was uncalled for. Ms. Sugawara said we should make a hub where people who had been forced to scatter across Rikuzentakata could get together. She even found a place that overlooked the whole of the city. And the moment we saw it, all three of us knew. Our intuition told us, this was the site.

I've always sought a new approach to architecture, tried to rethink it in abstract terms of where it started and ended. But with Rikuzentakata, the place itself brimmed with symbolism. Our mission was to restore the ties between people that had been severed by the disaster. I felt that our building was the start of a community, as well as the start of architecture.

This was another thing I gave thought to in the project--symbolism. Architectural features like the pillars representing a grove and the vertical structure representing a fire tower all emerged from this question of symbolism. I also wanted to incorporate into the building the topographical elements of Rikuzentakata surrounded by mountains.

Presenting the flow of time through photographs

HATAKEYAMA: I'm a photographer, so I didn't contribute too much to the actual design of the "Home-for-All." I just want to make this clear to begin with, in case any of you think that my being credited as an exhibitor means I was involved in the design process. I did attend the general meetings, but only to cheer on the team from my seat in the bleachers.

HATAKEYAMA: I'm a photographer, so I didn't contribute too much to the actual design of the "Home-for-All." I just want to make this clear to begin with, in case any of you think that my being credited as an exhibitor means I was involved in the design process. I did attend the general meetings, but only to cheer on the team from my seat in the bleachers.

As commissioner of the Venice exhibit, Mr. Ito initially asked me to recreate the flow of time in Rikuzentakata through photographs of the city before and after it was hit by the tsunami. Later, as Mr. Ito has mentioned, the plan changed to record the building process of an actual "Home-for-All" in Rikuzentakata. It was only at this point that I found out the team planned to build a real "Home-for-All" in my hometown. I never dreamed of that possibility until then, so I was delighted. Over the following six months or so, the "Home-for-All" took concrete shape, and the house is being constructed at this very moment. I don't think anyone foresaw this development. I'm deeply moved by the dynamic turn of events over the past year.

In the Japan Pavilion, I feel I took on the role of a narrator. I didn't contribute too much in terms of design there, either, but I'm under the impression that the photographs are helping the visitors to relate to the exhibit.

ITO: At the beginning of this year, Mr. Hatakeyama showed photographs of Rikuzentakata before and after the tsunami in his solo exhibition at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography. I asked him to exhibit similar photographs in Venice, complete with a panoramic image of Rikuzentakata more than a year on from the disaster.

This panoramic image is the most deeply moving photograph I've ever seen before. It emanates such a profound silence. And to me, the heavier the silence, the more the photograph unveils the emotions that went into shooting it.

Last year, when I asked Mr. Hatakeyama to join the Japan Pavilion exhibit, he said he wasn't yet ready to take pictures, that he wasn't feeling optimistic enough. So I imagine he didn't shoot the panoramic image in an entirely positive frame of mind. But I also feel that shooting the image helped him to break new ground.

The photographer must remain an outsider

HATAKEYAMA: Photographers are a unique breed. I'm credited as an exhibiting artist in the Japan Pavilion, but I was also in charge of photographic recording of the exhibit. One time, when the exhibit was complete and the team lined up for a group photo, I found myself standing behind the camera and not in front of it with the other members. I asked someone else to press the shutter button for me just that once, of course. But under normal circumstances, if there exists a world within the camera's view, by definition, the photographer must remain outside of it.

When an important event takes place in front of my eyes, unconsciously I slip outside of it and take pictures. So when someone praises my work, often it doesn't hit home right away. You said, Mr. Ito, that I may have broken new ground with the panoramic image. I can't make up my mind just yet whether I have or I haven't.

ITO: You said you took on the role of a narrator, Mr. Hatakeyama. Perhaps you meant the role of a photographer--someone who constantly remains an outsider. My impression is that, at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, I felt your presence within the photographs of post-disaster Rikuzentakata. But in the panoramic image at the Venice Biennale, I sensed you had once again slipped outside and focused on shooting the subject.

HATAKEYAMA: Speaking of the panoramic image, I'd like to offer the story behind it. I took that series of pictures on June 24 this year, from a heap of rubble near the Rikuzentakata train station.

The digital camera displayed a horizontal line in the middle of the viewfinder, which happened to align perfectly with the fourth-floor window of Iwate Prefectural Takata Hospital. When looking through the viewfinder, I remembered that this hospital was submerged from the fourth floor down. From there, I kept the viewfinder's line on the height of the tsunami and shot the 24 cuts that resulted in the 360-degree panoramic image.

I included a caption explaining this in the Japan Pavilion--"This photograph was taken from the height of the tsunami. Everything below this line of view was submerged." I think the photo with the caption has effectively made visitors notice that everything from their eyes down was underwater.

Two "Homes-for-All"--in Sendai and in Rikuzentakata

ITO: Let's bring the discussion back to architecture. The accounts of the three architects today have made me think. When I was interviewed as the commissioner last year, I said this exhibit would turn out to be nothing like an ordinary architecture exhibit. When an architect plans an exhibition, he/ she usually displays what he/ she knows or has completed already. Whereas this time, I had no idea what awaited a year ahead. The plan to co-design the "Home-for-All" might fall through midway, and already Mr. Hatakeyama mentioned he wasn't ready to take pictures. All three architects showed their hesitation in joining the project. Well, me too. I was anxious about how the project would turn out. In fact, I still am.

ITO: Let's bring the discussion back to architecture. The accounts of the three architects today have made me think. When I was interviewed as the commissioner last year, I said this exhibit would turn out to be nothing like an ordinary architecture exhibit. When an architect plans an exhibition, he/ she usually displays what he/ she knows or has completed already. Whereas this time, I had no idea what awaited a year ahead. The plan to co-design the "Home-for-All" might fall through midway, and already Mr. Hatakeyama mentioned he wasn't ready to take pictures. All three architects showed their hesitation in joining the project. Well, me too. I was anxious about how the project would turn out. In fact, I still am.

To me, the Miyagino "Home-for-All" that I built in Sendai, and the Rikuzentakata "Home-for-All" that is on its way to completion as we speak, are very different. When I first launched the "Home-for-All" project, there were three objectives. One, it needs to provide people living in temporary housing a place to eat together and chat with one another. Two, it needs to be made by everyone--residents, architects, volunteers--all together. And three, it needs to serve as a base for local residents to discuss about community regeneration.

In Miyagino, I feel I've accomplished the three objectives to a certain extent. There, I let go of the architect in me, so much so that I worried my associates. But the "Home-for-All" in Rikuzentakata is somehow different. Yes, we're working with local people engaged in support activities. But have we let go of the architects in us? Not quite, in a sense that the building reflects our originality.

Ms. Sugawara's activities thrive on one abstract question--How are we going to rebuild our lives? And the architects who are there to help answer that question also face an essential question--what is architecture? Somehow, to me, that's very architectural.

FUJIMOTO: I remember clearly the view on our way back to Tokyo after one meeting in Rikuzentakata. We were driving away, and Ms. Sugawara and the other residents waved goodbye until our bus was out of sight. Because the tsunami had washed away everything, there was nothing to block our view of the residents. We saw them waving forever and ever.

At that moment, a picture naturally popped into mind--all our minds, I think. What if these people were waving from the top of a vertical building? This view, and the story about the pine grove destroyed by the tsunami, and the idea of using the logs of Japanese cedar to build pillars... All of this welled up naturally in the course of our contact with Ms. Sugawara and the land of Rikuzentakata. This curious chain of events made the "Home-for-All" in Rikuzentakata different from that in Miyagino. In Rikuzentakata, letting go of 'architecture' was the furthest thing from our minds.

ITO: Let me get this straight. If there's no need to let go of architecture, then there's no need to let go of the architect, either?

FUJIMOTO: That's right. In some circumstances, it's best not to enforce our design or our originality. Keeping our eyes open for events unique to the site, recognizing what has welled up, and guiding others to embrace it--perhaps these are things only an architect can do.

Architecture tuned into unique circumstances

HIRATA: At the beginning of the project, Ms. Sugawara told us a story about one jazz drummer. Soon after the tsunami, a bunch of volunteers came over and performed music for the people living at the evacuation site. Well, this jazz drummer said he performed an improvisation resonating to the beat of the Earth, but Ms. Sugawara didn't quite get it. Some time later, singer-songwriter Tokiko Kato also came, and when she noticed that no one at the evacuation site was wearing slippers, she took off her shoes and sang barefoot. Ms. Sugawara said this was a far more touching gesture, and she felt a unity between stage and audience.

We talked about this later on, if we could be Tokiko Kato, or we were closer to the jazz drummer. We called this the "jazz drummer issue." That is, our ideas for architecture may mean well, but if they don't get the sympathy from the residents, they're a complete failure.

ITO: I'm confident you accomplished even more than Tokiko Kato. I'd consider the project a failure if you had designed the building only from the architect's egocentric point of view, without any discussion with the residents. But you did hold discussions, and you did incorporate the residents' views into the building. That's more than Tokiko Kato did.

HATAKEYAMA: I rather sympathize with the jazz drummer. He left a deep impression in Ms. Sugawara's mind, after all. That must count for something. Her reaction may not have been the one he expected. But who knows? The person standing next to Ms. Sugawara might have loved his performance. It's similar to works of art displayed in a museum.

Except, architecture engages in the public to a greater extent than paintings or music. It involves many more people, and much more money. So it only follows that the team of architects put that much more thought into the project.

INUI: The circumstances are quite different between the Miyagino "Home-for-All," which stands in a park, and the Rikuzentakata "Home-for-All," which we're building in a site with unique qualities. I think architecture is about being tuned into these individual, unique circumstances.

As for the 'jazz drummer issue', I have a feeling that Ms. Sugawara may be a sort of jazz drummer in her community. All those residents were deprived of life as they knew it. Some of them are motivated toward reconstruction, while others may give up hope. Ms. Sugawara is on a mission. She has an amazing will of power to do something about her situation. In her case, her energy may not strike the right chord with the community forever.

I think everyone needs a jazz drummer. No community can thrive without someone to add a spark of energy to it. The important thing is to help create a mechanism to attract sympathy to the jazz drummer. Wouldn't it be wonderful if the "Home-for-All" helps to spread the movement Ms. Sugawara started to other communities in Rikuzentakata and beyond?

Report photos by Kenichi Aikawa

[Japan Pavilion Commissioner]

Toyo Ito

Toyo Ito

Architect

Graduated from the University of Tokyo, Department of Architecture in 1965. In 1971, he established his own office, Urban Robot (URBOT), which was renamed to Toyo Ito & Associates, Architects in 1979. Main works: Sendai Mediatheque, TOD'S Omotesando Building, Tama Art University Library (Hachioji campus), The Main Stadium for the World Games 2009 in Kaohsiung (Taiwan R.O.C.), Toyo Ito Museum of Architecture, Imabari, etc.

Under development; Multimedia Complex on the site of Gifu University's School of Medicine (tentative), Taichung Metropolitan Opera House (Taiwan R.O.C.), etc. Awards and Prizes: Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement from the 8th International Architecture Exhibition "NEXT" at the Venice Biennale (2002), Royal Gold Medal from The Royal Institute of British Architects (2006), 6th Austrian Frederick Kiesler Prize for Architecture and the Arts (2008), The 22nd Praemium Imperiale in Honor of Prince Takamatsu (2010), etc.

[Exhibitors]

Kumiko Inui

Kumiko Inui

Architect

Born in Osaka Prefecture in 1969. Graduated from the Department of Architecture at Tokyo University of the Arts in 1992. Completed a master's course at the School of Architecture, Yale University in 1996. Worked at Jun Aoki and Associates from 1996 to 2000. Established the Office of Kumiko Inui in 2000. Currently serving as an associate professor at Tokyo University of the Arts. Her important works include the Kataokadai Kindergarten Renovation (2001), Jurgen Lehl Marunouchi (2003), Dior Ginza (2004), Apartment I (2007; recipient of Shin-Kenchiku Prize), Small House H (2009; recipient of Tokyo Society of Architects & Building Engineers Prize), Flower Shop H (2009; recipient of Japan Federation of Architects & Building Engineers Association Prize, and the Good Design Gold Award), and Kyoai Commons (2012). Her published works include Episodes (INAX, 2008) and Home of Asakusa (Heibonsha, 2011).

Sou Fujimoto

Sou Fujimoto

Architect

Born in Hokkaido in 1971. Graduated from the Department of Architecture in the Faculty of Engineering at the University of Tokyo. He established Sou Fujimoto Architects in 2000. In 2008, he received the Japan Institute of Architects (JIA) Award and the grand prize in the Private House Division at the World Architectural Festival. In 2010, he received the Spotlight: The Rice Design Alliance Prize. His most important works include the Children's Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation (2006) and the Musashino Art University Museum & Library (2010).

Akihisa Hirata

Akihisa Hirata

Architect

Born in Osaka Prefecture in 1971. Graduated from the Department of Architecture in the Faculty of Engineering at Kyoto University in 1994. Completed a master's course at the same university in 1997. After working at Toyo Ito & Associates, he established akihisa hirata architecture office in 2005. At present, a specially-appointed associate professor at Tohoku University, a part-time lecturer at Kyoto University and Tokyo University. Among the many honors, he has received are SD Review's Asakura Award (2004) and 2nd prize of the Kaohsiung Maritime Cultural & Popular Music Center International Competition (2011). His important works include Masuya (2006; received 19th JIA Newcomer's Award), Alp (2010), Bloomberg Pavilion (2011), Coil (2011) and Photosynthesis (2012; received Elita Design Award). His published works include Contemporary Architect's Concept Series 8: Tangling (INAX, 2011).

Naoya Hatakeyama

Naoya Hatakeyama

Photographer

Born in Rikuzentakata, Iwate Prefecture in 1958. Studied with Kiyoji Otsuji in the School of Art and Design at the University of Tsukuba. Completed a master's course at the same university in 1984. Since that time, Hatakeyama has been based in Tokyo, producing series of works that are concerned with people's involvement with nature, the city, and photography. He has participated in numerous solo and group exhibitions both in Japan and abroad. In 2001, he showed his work in the Japan Pavilion at the Venice Biennale along with Masato Nakamura and Yukio Fujimoto (commissioner: Eriko Osaka). An exhibition called Natural Stories, which included scenes of his hometown of Rikuzentakata following its destruction in the tsunami, was held at the SFMOMA from July 28 to November 4, 2012.

Related Events

Keywords

- Photo

- Architecture

- Culture and Society

- Social Securities/Social Welfare

- Natural Environment

- Rikuzentakata

- Home-for-All

- International Architecture Exhibition

- Venice Biennale

- Great East Japan Earthquake

- Golden Lion for Best National Participation

- Miyagino Ward of Sendai City

- Mikiko Sugawara

- temporary housing

- Kenka tanabata

- Debris

- Disaster utopia

- Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography

- Volunteering

- Tokiko Kato

- Reconstruction

Back Issues

- 2025.6. 9 Creating a World Tog…

- 2024.10.25 My Life in Japan, Li…

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.5. 2 People-to-People Exc…

- 2024.5. 2 People-to-People Exc…

- 2023.12. 7 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2023.6.16 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2023.4.24 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2022.12.27 Living Together with…