What Literature Can Do -- Conversation between Two Novelists and One Translator

Laird Hunt (Novelist)

Motoyuki Shibata (Translator)

Hideo Furukawa (Novelist)

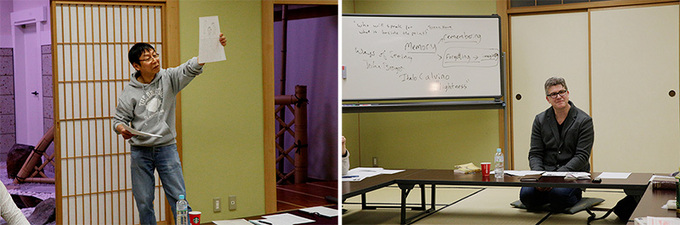

Hideo Furukawa, who is always passionately active; Laird Hunt, who visited Japan from the U.S. to celebrate the publication of his second novel translated in Japanese, Kind One; and translator Motoyuki Shibata, who has introduced Japan to a multitude of authors in the English-speaking world. These three individuals established themselves firmly into the world of literature and quickly became regular voices in the field. On December 2nd, these three came together to discuss the subject, "what literature can do." Just a few days before that, the three of them had attended Hideo's literature school, the Drifting Classroom, as teachers. So they talked about how the school went, what role reading their literary works aloud plays, and so on. As the one and a half hour talk progressed, it gradually became more and more profound.

====

JFIC Event 2015: Wochi Kochi Magazine Talk: What Literature Can Do

Laird Hunt (novelist) × Motoyuki Shibata (translator) × Hideo Furukawa (novelist)

(December 2, 2015, at the Japan Foundation's JFIC Hall "Sakura")

====

Reading excerpts from Kind One and The Book of Three Hundred Treacherous Women: the words and stories of two literary works blended by these three individuals

The meeting of the three individuals and the Drifting Classroom

Hideo Furukawa (HF) - First, shall we hear from Moto the details of how the U.S. novelist Laird Hunt came to be here today?

Motoyuki Shibata (MS) - It began with my encounter with and translation of Laird's novel, Indiana, Indiana. I am working as the editor for the English-language literary magazine Monkey Business (published in the U.S.), which holds an event once a year in New York to celebrate its publications. At the 2014 event, I requested a dialogue between Hideo and Laird, which turned out to be astounding. Although these two men were writing about completely different things, I felt that they were authors who had a lot in common.

HF - Therefore, when I suggested that we try inviting a teacher from overseas at the Drifting Classroom, where I work as headmaster, it was clear that it just had to be Laird and nobody else.

MS - At the Drifting Classroom, even though I am not a member of administrative staff, for some reason, my role is similar to that of a deputy headmaster. (Laughs)

Laird Hunt (LH) - Talking at the event of Monkey Business in New York was quite exceptional. Of course, I have been in dialogue with many different writers, but I felt like we were having a mind-meld that afternoon in New York. Naturally, when I was invited to attend the Drifting Classroom...

MS - Not even an hour later, the reply came, "YES!!!" (Laughs)

Laird talking about the details behind this trip to Japan

HF - When I read the first Japanese translation of Laird's, Indiana, Indiana, I had a feeling that it was utterly different from my own novels. And yet, the way that time and space reverberated off one another in the story actually felt very similar. Our readership may not overlap, but we are perhaps close as authors.

MS - I feel that the sense that they have with respect to place is similar. For example, when authors write about Tokyo, it is not unusual for them to reveal places that differ from the Tokyo that is visible to everyone. However, Hideo takes us inside of a Tokyo that everyone sees, and there, we find a new layer to it. Similarly in Laird's novels, take Indiana, Indiana for example, despite writing about Indiana in the midst of the 20th century, a layer of a time in the more distant past can be felt, and conversely, there are aspects in the novel that bring one toward the contemporary. In that way, there are a variety of layers to a single place, and I feel that both authors share the way they write about things that evoke feelings in a sensory manner.

HF - When Moto describes me, he says I am an author, not of "anti-" or "non-" but of "into-." I think Laird is such an author as well. Now, we just finished the fourth Drifting Classroom, including its branch school, a few days ago (editor's note: it was held over the weekend, three days before the talk, from November 28th to 29th). So, how was it?

MS - I have been attending it each time so far as a teacher, but this one seemed like the best yet. I felt that especially during the Home Room where all of the teachers took the stage and discussed that day's topic.

LH - To be honest, before I attended the Home Room on the first day, I had expected presentations of each teacher would not be easily connected. There were novelists, a translator, a literary critic, a sociologist, a calligrapher...such a variety of people, and what we did in class was quite different. However, when I listened to each individual talk, all of the things we had done had much in common. I felt that again on the second day, when Haruki Murakami spoke.

HF - This year, we had Haruki-san come as a secret guest, and he held a workshop together with high-school students from Fukushima. After that, we gave a joint talk, five of us in total, us three together with Mieko Kawakami and Haruki Murakami. I assume you mean that time, right?

LH - Yes. It was an unprecedented situation that I had such an iconic author so close to me!! (Laughs) Actually, he was simply one part of a conversation rather than being the center of the conversation.

HF - I already explained this when I asked Haruki-san to be a teacher, but I started the Drifting Classroom after feeling that I wanted to make a school for people who have found themselves lost for words in the face of catastrophe, or for people who have no means to put their ideas into words. All of the teachers understand this, and have conducted their classes from the viewpoint of what one should actually do, rather than talk about it directly. For this, I am very glad.

LH - The students also had a positive attitude in class.

MS - After the Great East Japan Earthquake, people involved in art and literature frantically wondered if there was anything they could do to help. This led some of us to join in with social action, but many of us focused on trying to put even more of our hearts into doing what we always do. I believe that each of the classes in the Drifting Classroom is conducted with that kind of spirit.

Workshops at the Drifting Classroom

What should literature do in the face of disaster?

Hideo Furukawa is also the headmaster of the Drifting Classroom

HF - I have said that the Drifting Classroom began as a direct result of the disaster of the Great East Japan Earthquake. In addition to this, a "post-Earthquake literature" genre appeared in Japan. How does this appear from your perspective, Laird, as an American? For example, is there such a thing as "post-9/11 literature?"

LH - I was in the Lower East Side of New York on September 11. I believe I underwent a significant change over that day. So many writers and artists, after that event, had a desire to do something. However, there were not many collaborative efforts in terms of writing, unlike the collaboration embodied by the Drifting Classroom. Of course, we call them all disasters, but each differs completely: what happened in New York was an attack by humans, while what happened in Fukushima was an attack by nature and the resultant combination of a natural and man-made calamity. So I think it is difficult to describe them all in one word.

MS - I think that Laird's full-length novel, The Exquisite, has a setting that never would have been written about if 9/11 had not taken place. Other than that, if we look at the recent short stories by Kelly Link for example, they take the idea that the world has already crumbled, as if by default. Personally, I feel that whether it is literature following 9/11 or the Earthquake, there is indeed a strong sense that the world has collapsed. Yet right now, I think caution is required in writing about this as a mass phenomenon as we may lose sight of the differences between individual people.

LH - After 9/11, we heard over and over again that "Now is not the time for experimental novels" or "Now is not the time for poetry." With almost every part of myself I said "No. Now is the time for poetry. Now is the time for complexity." Books are amazing at forming community, building conversation, and starting arguments. For instance, I can be sitting in Colorado where I live, reading a novel by Hideo, and feel no distance whatsoever. Literature becomes an opportunity to realize something, or start a dialogue with one's surroundings. Therefore, I believe that after 9/11, the role of literature grew deeper and more interesting than ever before.

HF - Books are tools that enable us to come and go, even if we are in a land with different scenery. I too, see it in that way. The meaning of "disaster" to each of us varies; our starting points and our positions also vary. But we are living in the same era. It is perhaps this sense of the same time that is most important. What do you think? Are there any questions from the audience so far?

Motoyuki Shibata talking about Laird's literary works

--- Laird, you have spoken about the atmosphere surrounding literature directly following 9/11, but what do you think about the literary work after that time? I feel that a sentiment expressing that "now is not the time for literature" pervaded in Japan as well after 3/11. How should we go about dispelling such an atmosphere?

LH - Right after 9/11, when various authors were releasing literary works about the incident, I felt it was a little too soon and that we should have spent more time digesting what had happened and thought about it in all dimensions. This may also be an attitude that comes from my own style of writing. That is basically what I think even now. On the other hand, I recognize the suggestion that the things written directly afterwards could only have been written at that time.

HF - I differ from Laird on this point: I started writing immediately after the Earthquake, and have a literary work that was published less than three months after, Horses, Horses, in the End the Light Remains Pure. To be honest, I truly hate the term "3/11." The words are misleading, and suggest the disaster happened only on that day. Yet in reality, crises are still ongoing and continuing to arise in my hometown of Fukushima. I realized that if that is how it is, then I had no choice other than to continue writing out of desperation, even if the end result was not something that could be called a novel. If it was the kind of situation that left me, someone involved in literature, lost for words, then what I had to do was to express out loud that I was "lost for words" or at least recognize that I was. Although literati should not say they are "lost for words," I thought expressing it would have to become literature. That being said, the book I wrote is now being published in English this spring (March 2016), five years after the Earthquake, by Columbia University Press. I hope that by some chance, the fresh words from those days may establish some kind of value.

MS - If I may give my personal view on the question posed in the latter part just now, I think that in fact, there has never before been an era with "time for literature." We used to feel that literature was something we had to revere, but that kind of elitism died over the past 30 years. I think that in and of itself, it is a healthy situation, because people now read because they want to, not because they feel they have to. Those who do read, they read passionately. Obviously, knowing this, I hope to see more and more people reading.

HF - Because I have just recently been active as the headmaster at the Drifting Classroom, I tend to conclude things like a teacher (laughs), but I hope that you will all take something away with you from our talk today and think it over. For example, try looking at Tokyo through Laird's eyes, I mean, with the viewpoint that your presence is alien. Remember that the present includes both the past and future, and for that very reason, there are things you can do.

Commemorative photograph of each man with his own literary work

(Text: Sawako Akune / Photos from the talk event: Kenichi Aikawa / Video: Hiroki Kawai and Taiyo Morishige / Interpreter: Tsukushi Ikeda )

This event is now in abridged form, and can be viewed on YouTube.

Literary School "The Drifting Classroom"

Laird Hunt

Laird Hunt

Laird Hunt is a novelist and professor at the Department of English of University of Denver. Born in Singapore, he now lives in Boulder, Colorado, the United States of America. His novel Indiana, Indiana (Asahi Shimbun Publications) was published in Japan in 2006, translated by Motoyuki Shibata, and in October 2015, his long-awaited second Japanese translation, Kind One (Asahi Shimbun Publications) was released. Before becoming a novelist, he spent five years working as a press officer for the United Nations. To date, he has lived in a number of countries, including Japan, France, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands. His recent literary work, Neverhome (Little, Brown; not yet published in Japan) was chosen to be adapted into a movie, and was awarded the Grand Prix de Littérature Américaine in France.

![]()

Motoyuki Shibata

Motoyuki Shibata

Motoyuki Shibata was born in Tokyo, and is a translator and a project professor at the University of Tokyo. He has translated a great many contemporary American works of literature, by authors including Paul Auster, Rebecca Brown, Steven Millhauser, Stuart Dybek, and Philip Roth. In 2010, he won the Japanese Translation Cultural Award for his work on Mason & Dixon by Thomas Pynchon (Shinchosha). He is also the editor of the literary magazine MONKEY (Switch Publishing). His recent translation works include Moby-Dick in Pictures: One Drawing for Every Page by Matt Kish (Switch Publishing) and Zeroville by Steve Erickson (Hakusuisha Publishing).

Drawing ©Satomi Shimabukuro

![]()

Hideo Furukawa

Hideo Furukawa

Novelist Hideo Furukawa was born in Koriyama City, Fukushima Prefecture. In 2002, he received the Mystery Writers of Japan Prize and the Japan SF Grand Prize for The Arabian Nightbreeds (Kadokawa Shoten). In 2006, he won the Mishima Yukio Prize for LOVE (Shinchosha). He opened a literature school, the Drifting Classroom which has no fixed school building, in 2013, and works there as the headmaster. The Book of Three Hundred Treacherous Women (Shinchosha), which he published in 2015, won the 37th Noma Literary Prize for New Writers and the 67th Yomiuri Prize for Literature. His latest work is Aruiwa Shura no Juoku-nen [Or A Billion Years of Asura].

Back Issues

- 2025.11.14 Stories from Both Si…

- 2025.10.24 Dialogue through Ani…

- 2025.6. 9 Creating a World Tog…

- 2024.10.25 My Life in Japan, Li…

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.5. 2 People-to-People Exc…

- 2024.5. 2 People-to-People Exc…

- 2023.12. 7 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2023.6.16 The 49th Japan Found…