005 You Plant A Seed, You Watch Your Seed Becomes A Tree, You've Made Art

Prabda Yoon

Writer and publisher

It's somewhat of a cliche to say that Filipinos and Thais look alike--and I think they generally don't--but it's fair to say that the two do commonly get mistaken for one another by foreigners. More intriguing, for me at least, is the fact that while the Philippines obviously belongs in Asia, and its peoples are of the Asian race, the country's culture is vastly different from the typical perceptions of "Asian," let alone Thai. Perhaps it's because, as my Filipino friends like to say, Filipinos are Spaniards who see themselves as Americans. The Philippines were colonized by Spain for over 300 years, then after the Spanish-American War and the Philippine-American War popular Americanism took over. The effect seems to be permanent. Being in big Philippine cities such as Manila or Cebu feels more like being in California and Florida than being in Bangkok, Beijing, or Tokyo.

Yes, Americanism is now close to being airborne, evident even in obscure corners of the world, but in most places the people don't necessarily see themselves as Americans. They endorse American materialism, can't live without American junk food, crave Hollywood blockbusters, and worship American icons, yet they also see themselves as having a separate identity. Some of these people even hate America; they adore Micky Mouse but despise Walt Disney. That's not the feeling one gets in Manila or Cebu. The Filipino elites and ruling classes behave as if they're in America. Indeed they frequently visit their "motherland." A Filipino friend, a well known writer, admits to me once that this is a typical complex of modern Philippine society. "We never look to Asia," he said. "When we look out, we see only the United States."

When I visited the Philippines for the first time in 2002, and several times after that, I stayed only in Manila. Naturally, all I saw and felt there was the product of that American complex. It was only in 2009 that I was able to get closer to what lied within. Why did I want to get closer? What was my objective for getting to know the Philippines? Frankly, I have no answers. Apart from a group of friends I've made over the years from my visits, I have no other connections to the Philippines whatsoever. Yet whenever I had the chance to return, I grabbed it. Perhaps because I was always fascinated by how different it felt from being in other Asian countries. Perhaps I wanted to find out why it felt that way. Perhaps it was just interesting to be surrounded by people who looked similar to the people in my own country but who acted as if they were Americans.

Whatever the reason, I now see the Philippines in a completely different light, and its American complex no longer means anything to me when I think about the place. In 2009 and 2010, for a total of about 4 months, I traveled across that country, stayed in local and rural towns, and sailed to several of its thousands of islands. I experienced how it was to be trapped indoors for weeks during a typhoon attack. I made long, adventurous trips to volcanoes, both active and dead ones. I flew on an airbus in a heavy storm from Manila to Mindanao, and when the craft safely landed I couldn't help but wonder how it was possible that I survived. To sum it up, my stay in the Philippines this time was an eye-opening, at times almost heart-stopping, journey. There was never anything American about any of it, except maybe for the occasional American cable TV programs I watched in hotel rooms.

One of the most interesting encounters (there were a lot more than one, believe me) I had in that time was with an art teacher in Davao named Ric Obenza. I went to Mindanao hoping to interview some artists about their views on the relationship between art and nature. I had talked with a number of artists, musicians, and writers before I met Obenza, and I was surprised how much "nature" there was in the general psyche of the Filipino creative community. Before I arrived in the country for the research, I'd expected to find the opposite; I thought the artists would all talk postmodern theories and conceptual jargon, the way they did in America. I couldn't be more wrong. Almost all the people I met had very clear and articulate insights about nature to share. One of them, a popular musician, even showed me a collection of elaborate drawings and diagrams he made to show how all lives on this earth were interconnected. I'd thought I would have a hard time with my research in the Philippines, but it turned out to be so easy. Everyone knew how he or she felt about the presence of nature in his or her life and work.

But no one expressed his thoughts on nature to me quite the way Ric Obenza did. Obenza, a man that looks to be in his 50s, teaches at an elementary school in Davao, and he's not a famous artist. Compared to the rest of the people I interviewed in the Philippines for my research, Ric Obenza was a complete unknown. He's just a modest, local activist, yet the way he lives and teaches seems to me to be a work of art in itself.

Ric Obenza, activist, teacher, artist

The first time I met him was at a cafe and he seemed suspicious of my request. He spoke little, his answers distant and forced. I later realized that the meeting place must have been too urban, too alien for him, making him uncomfortable and nervous. After an hour or so of getting only short, vague replies from Obenza, I thought my conversation with him would end up unusable. But when I ran out of things to say, he suggested that I come over to his house the next day. He said, "First I'll show you my drawings and paintings, then I'll take you to my mountain." I thought he was joking, but it was true. Ric Obenza owns a mountain, and that's where his true art comes to life, literally.

Ric Obenzaís Mountain

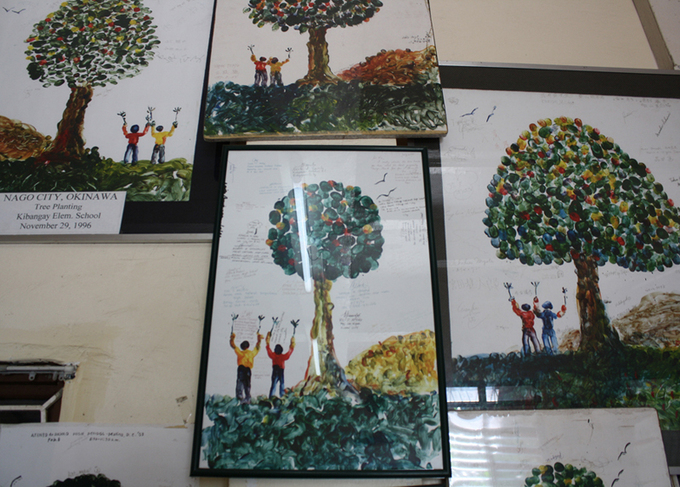

Ric Obenzaís painting

The second time I met Obenza, I soon found myself following him, and his climbing stick, up a hill through tall trees, large roots, and giant rocks. It was a real climb, not a tourist trekking trip. It was through a real forest, up a real mountain, not just some prepared, casual eco-vacation setting. At one point I asked myself what I was doing and why was I letting a man I barely knew lead me deep into a remote and dangerous place. There were many moments in the Philippines when I suddenly thought, "This must be it. This is where my body will be discovered. This is where my short life will end." I almost had that thought on Ric Obenza's mountain too, but only almost. When we neared the mountaintop, Obenza started to talk art, nature, and life. It was among the most inspiring walks I'd taken with anyone. He said that he would bring his students up to this mountain the same way he was now taking me, then when they reached his camp up top each student would plant a seed in his garden. He would tell them to take care of their own seeds, and he would bring them back regularly to paint their own trees as they grew. "My way to teach children about nature, about how we should be kind to the earth, is to show them that they're all responsible for life on the planet. If they have they own trees, they will understand that nature is alive, that they should not cut down trees for selfish purposes." Obenza told me that some students, after they'd left school and grown up, would return to thank him for his lesson, for his seeds. That's what Obenza counts as his success. "Art happens when you learn something from nature," he said. It's a rather vague statement, but one that triggers countless moments of contemplation in my mind. Perhaps art is not what one makes or what one sees, but what one manages to cultivate from the process of art making. Mountains, museums, or galleries, what matters most may be what one keeps within after the experience, not what one saw or touched in the environments.

Following Ric Obenza up to his camp

Obenzaís studentsí paintings on the classroom wall

Obenza's students' paintings

When we finally reached the top, Obenza took me straight to a vegetable garden at his camp. "You know," he said with a hint of pride in his voice, "I learned one important secret from all these years of teaching and working with nature." I was ready for some kind of mind-blowing wisdom about life, art, and the universe. Obenza smiled and reached out to a small plant. He nipped a small red chilly pepper off its branch and put it in his mouth whole, then started to chew enthusiastically. "I've learned that chilly peppers are the best remedy. Make a habit of eating it fresh all the time and you won't ever get sick again."

He handed me one and I quickly put it in my mouth the same way he did, to show off my bravery. It burned my tongue, and tears formed in my eyes, but I kept on smiling. Ric Obenza's wisdom is not exactly about art, but perhaps his discovery about chilly peppers is what interconnection between art, life, and nature really means.

Prabda Yoon

Prabda Yoon

Born in 1973, a Thai writer and publisher based in Bangkok. He has published numerous novels, short story collections, and essay collections. In addition, he has also translated modern English-language classic literature such as The Catcher in the Rye and A Clockwork Orange into Thai. In 2002, his short story collection, Kwam Na Ja Pen (English: Probability), won the SEA Write Award.

Apart from working in Thailand, Prabda has regularly written for Japanese magazines and exhibited artworks in Japan. He has written 2 screenplays for films starring Tadanobu Asano and he is presently collaborating on various art projects with Japanese contemporary artist Kohei Nawa. His literary works have been translated into Japanese, of which the most recent is the novel Panda.

Back Issues

- 2022.7.27 Beyond Disasters - T…

- 2022.6.20 Beyond Disasters - T…

- 2021.6. 7 Contributed Article …

- 2021.4.28 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2021.4.27 Contributed Article …

- 2021.4.20 Contributed Article …

- 2021.3.29 Contributed Article …

- 2020.12.22 Interview with the R…

- 2020.12.21 Interview with the R…

- 2020.11.13 Interview with the R…