Crossing Borders, Engaging in Exchanges and Harnessing the Power of Creation amid COVID-19

Interview and Contribution Series <7>

Osawa Torao, NLI Research Institute

April 28, 2021

[Special Feature 073]

In this seventh issue of our special feature "Crossing Borders, Engaging in Exchanges and Harnessing the Power of Creation amid COVID-19" (click here for a special feature overview), we welcome this contribution by Osawa Torao, Senior Researcher, Center for Arts and Culture, NLI Research Institute. He researches cultural policy and art management and observes local culture as an "ecosystem" as he travels between Fukuoka, Tokyo and Germany. In this essay, Mr. Osawa talks about crossing national borders amid the COVID-19 pandemic. He also explores the possibilities for communication that transcends our "walls" as seen in a performance by Tezuka Natsuko, his partner as well as a dancer and choreographer, which was conducted at the Japan Cultural Institute in Cologne in October 2020.

Clumsy Manners for Facing Invisible "Walls"

Osawa Torao

Before heading into the main topic, I'd like to explain a bit about my own eccentric circumstances. I work at a think tank called the NLI Research Institute and undertake research on cultural policy and art management. My partner is Tezuka Natsuko, a contemporary dancer and choreographer, and we have a son who turned 16 in 2020.

Wishing to change both my life and work style in the aftermath of the Great East Japan Earthquake, I moved with my family from Kanagawa Prefecture to Fukuoka Prefecture in 2013. In conjunction with this move, the NLI Research Institute amended the format of my contract so that I could remain employed. For seven years since then, I have worked remotely while traveling back and forth between Fukuoka and Tokyo. However, in 2018 Tezuka decided to move to Berlin, Germany, to take on the challenge of continuing her dance activities. Our son, who was 13 at the time, chose to live with her while I remained in Japan to undertake my research. Since then, I've been checking on their well-being and discussing current events through online video calls almost daily, and staying in Berlin for several weeks every summer and winter became my regular lifestyle pattern.

This lifestyle was abruptly upended, however, when the COVID-19 pandemic struck. The virus led to restrictions on traveling abroad, making it unclear when I could meet my family again. In mid-July 2020, I explained our situation via e-mail to the German Consulate in Japan and to the German Federal Police Bureau at Frankfurt Airport, which controls entry into Germany. I received a reply informing me that "If your wife and your son have a valid residence permit, entry should be possible."

I promptly booked a flight and departed Tokyo's Haneda Airport on August 1, 2020, taking a copy of my family's visa. I arrived at Berlin Tegel Airport the following day. While standing in the immigration line for non-EU citizens, a man in front of me who appeared to be from a Southeast Asian country underwent a lengthy interrogation by an immigration officer. There seemed be some complicated circumstances, and then right before my eyes, the man was escorted to a different room by another immigration officer. Worried if I might be forced to return to Japan, I nervously showed my passport to the immigration officer, who asked whether my family lives in Berlin and how long I intended to stay. The officer then nonchalantly stamped my passport and returned it to me and said "Have a nice day!" It was just like that. To be honest, I was astonished.

Reflecting back on this now, I realize just how "strong" Japanese passports really are compared with those of other countries. Japanese passport holders are allowed visa-free entry into the largest number of countries and regions in the world. The passport held by the man in front of me at the airport was probably not so widely accepted for entry. This made me realize that during this pandemic I was at an actual border location where a passport alone determines a person's freedom of movement.

In Japan and Germany, responses to COVID-19 as well as people's attitudes varied greatly. Germany was able to relatively hold down the number of coronavirus infections compared with other European countries. That said, infection levels are still quite high compared with the numbers in Japan. The German federal republic and state governments have issued a mask mandate in public spaces and fines are imposed for any violations. For this reason, there were no maskless people in such indoor spaces as public transportation or commercial facilities. In stark contrast, almost nobody wore masks in such public places as streets, parks and other large open areas even when these spaces were somewhat crowded. The situation is completely different in Japan, where people actively avoid the "3 Cs," while measures such as temperature checks and disinfecting are thoroughly implemented indoors. In Japan, not only does everyone wear masks in indoor public spaces but large numbers of people also wear masks outdoors. Compared with this tight vigilance in Japan, in a word I can only describe the atmosphere in Berlin as being quite lax.

Photographed on a weekend. Very few people wear masks outdoors when spaces are not crowded.

Photographed on a weekend. Very few people wear masks outdoors when spaces are not crowded.Still, I sensed there are fundamental cultural differences between Japan and Germany that can't simply be attributed to being lax. In Japan, there was a social phenomenon whereby citizens clamped down on their compatriots out of a sense of justice and anxiety over COVID-19. This could be seen with citizens keeping vigilant eyes on fellow citizens whether they are following stay-at-home requests, wearing masks or not traveling to visit their hometowns. Alternatively, in Berlin there was a huge demonstration against a mask mandate. According to media reports, the demonstration drew about 38,000 participants. People with extremely divergent ideas and values, from persons protesting the infringement on individual rights and freedoms to anti-vaxxers and far-right forces dissatisfied with the current government, gathered together at a single location to raise their voices in protest. A spectacle like that is unthinkable in contemporary Japan.

I personally encountered two mask-related incidents in Berlin. One involved a man who was not wearing a mask while riding in a quiet subway car with few passengers. A man wearing a mask who was sitting across the aisle called out to the unmasked man. I'm not sure exactly what they said because they were speaking in German, but based on their gestures and manner of speaking, I'm guessing they probably had the following conversation.

Masked man: "Why aren't you wearing a mask?"

Maskless man: "I won't wear a mask."

Masked man: "Do you want a mask?" (He then pulls out a bundle with about 30 paper masks.)

Maskless man: "I don't need one. I don't want to wear a mask."

Masked man: "Oh well, I tried anyway."

The conversation between the two ended and the subway train was quiet again.

On a different day, I witnessed another incident. In a moderately crowded car on the S-Bahn (city center loop line that runs above ground), a woman insisted that an unmasked man put on a mask. Subsequently, the two continued to argue endlessly. I'm not quite sure of the details, but their thundering voices reverberated throughout the entire carriage. It appeared that ultimately the maskless man was worn down by the woman demanding he wear a mask. The man hurriedly scampered off at the next stop.

The conversation on the subway and the argument on the S-Bahn made me think that such scenes were truly unique to Berlin. People there directly inflict their own opinions on others, whether they are compromising or arguing. They didn't seem to care what other passengers thought while the passengers themselves paid scant attention. This made me wonder about how to explain culture in Japan, where behavioral norms are created by peer pressure to take a hint without having to actually voice one's opinion.

On this most recent trip, I stayed in Berlin for about two months from August 2020 to spend time with my family. However, this visit was not a long leisurely vacation because I remotely worked every weekday. As I mentioned above, I'd already been doing so since long before the outbreak of COVID-19. This made me realize I could work normally whether I was in Japan or overseas as long as I had access to a Wi-Fi environment. In fact, prior to this visit I'd never experienced a single problem while staying in Berlin. This time, I encountered several small hitches.

My wife and son had just moved in to a new apartment a month before I arrived in Berlin. Despite concluding a Wi-Fi contract, its terms stipulated that if the monthly data volume limit is exceeded, then a restriction on communications would be imposed and the service would be cut off. To make matters worse, we couldn't immediately amend the contract. Without an Internet connection, I wasn't able to work. So I hastily rented a mobile Wi-Fi router for travelers with supposedly unlimited data volume. However, my communication immediately became restricted. I contacted the rental company and was told to wait until they send me a replacement SIM card. During this time, I couldn't connect to the Internet. I was stressed out numerous times because I was at my busiest exchanging crucial emails for my job.

It was also at such times that I became acutely aware of just how much I personally, and society as a whole, are dependent on the Internet. I'm sure I'm not the only person in the world who spends more time on a computer or smartphone than I do away from them during normal waking hours. There are likely many people who have become even more dependent on the Internet during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anyone can work from home with a Wi-Fi connection and a computer. Anything can be delivered by ordering online. Anyone can communicate online with people in far-flung locations.

COVID-19 restricts physical mobility and requires social distancing. This is fueling a continually growing need for the Internet as an alternative to mobility and for shrinking distances. Particularly noteworthy, as COVID-19 forces cross-border exchanges to migrate toward online formats, the infrastructure enabling these exchanges is being managed by the global information industry.

Using the Internet means that we continuously send information about our daily activities to people in the industry. Advertisements for products searched for yesterday are still displayed today. What people did on this date one year ago, places they visited this month and news that interests them are all automatically displayed. On the surface it appears we are the ones using the Internet, but in fact it's some distant system that directs our interest, managing, monitoring and controlling us. Even with this awareness, we can't completely break away from our dependence on the Internet.

The wall that separated East from West was torn down 30 years ago, paving the way for global-wide freedom of movement and communications. Nevertheless, throughout the world we are constantly at the mercy of conflicting information between facts and fake news. Divisions are appearing, spreading and deepening everywhere. I also get the sense that the Internet is responsible for driving these divisions.

In February 2020, the BBC reported that in 2019, the Internet was intentionally blocked more than 200 times in 33 countries around the world and that restricting access to the Internet has become a decisive tool for applying national pressure according to human rights groups. Could we possibly survive if the Internet was to be suddenly cut off?

For example, what if for some reason a powerful computer virus spreads out of control in the same manner as the global spread of COVID-19, causing the digital technology infrastructure to cease to function and social and economic systems to fail? What if this occurred at the same time as a global pandemic like the one we are experiencing and people are unable to move or leave their homes and the production and distribution of life-sustaining products and services grind to a halt?

I can't even envision such a scenario. But around one year ago, I also couldn't even imagine that COVID-19 would suddenly reshape our world in 2020. Even so, a simultaneous spread of a virus among living beings and among computers wouldn't be too surprising. In this instance, could we as humankind survive while we remain so divided?

As I explained at the outset, Tezuka Natsuko, who is my partner as well as a dancer and a choreographer, has been residing in Berlin since 2018. She basically uses English to communicate in her everyday life and dance activities. Almost all Germans and non-Germans, except for Japanese people, respond in English to her faltering English. There are of course situations where she must use German. She studied at a German language school but still can't converse fluently. She has run into a language barrier and struggles with this daily. She knows first hand that she can't live without the help of numerous people.

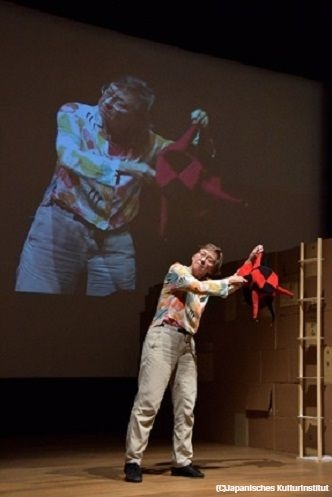

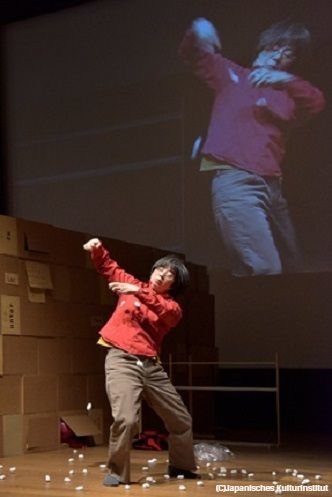

In October 2020, Tezuka was given the opportunity by the Japan Cultural Institute in Cologne (the Japan Foundation) to create her first full-scale work in Germany. (The performance is being streamed on the official YouTube channel of the Japan Cultural Institute in Cologne*¹). The creation of the work, entitled "「壁」と戯れる/Mauerspiel," meaning "Playing with the 'Wall'" both in Japanese and German to symbolize the content of the work, started at a workshop in September. For this workshop, she recruited native German speakers who can't speak Japanese. The work resembled a game of charades and cast a spotlight on discrepancies and misunderstandings that occurred between the German participants and Tezuka, who can't speak German, from being unable to understand each other's languages. The game was played by trial and error. The work consisted of displaying on stage human bodies colliding head-on with a linguistic wall. The performers mutually exchanged bodily expressions in an attempt to communicate. In the program guide for this performance, Tezuka sent the following message.

What is the meaning of communication to every person who lives in our ever-evolving modern world encased by global social media? Also, what will result from the sense of distance between people arising from various restrictions in the post-COVID era? While considering these questions, we agonize in weariness and play around with the "communication wall" to see what kinds of media the human body can become and explore various possibilities.

During the stage performance, a German woman named Evelyn clumsily communicated with Tezuka. This clumsiness is both humorous and frustrating. Nevertheless, through their strong determination to mutually communicate despite repeated discrepancies and misunderstandings, I feel that more value is created than all the words can say. This value is perhaps created in the same manner as when a parent and an infant who can't yet speak mutually sympathize with each other. Or perhaps this value would be created even in situations where someone drifts ashore onto an unknown island and asks the local people for help. But unfortunately, this value cannot be created through communication on the Internet.

Tezuka Natsuko's "「壁」と戯れる/Mauerspiel" (at the Japan Cultural Institute in Cologne)

Tezuka Natsuko's "「壁」と戯れる/Mauerspiel" (at the Japan Cultural Institute in Cologne)In our daily lives and work, we seek out correct understandings with no misunderstandings or discrepancies. On the other hand, if clumsy communication displayed by Evelyn and Tezuka is seen as just a time-consuming, irrational, inefficient and meaningless act, then perhaps the inhabitants of our world have lost their immunity to and tolerance of clumsiness.

Can a wall be surmounted as expected if the words can be understood correctly? Are languages the wall to inhibit communication? What exactly is the true essence of a wall? I have the feeling these questions are being asked to all of us.

People or countries can't understand or sympathize with each other just by correctness. The concept and definition of "correctness" differ among people and countries, and there are conflicts over correctness that ultimately create walls. Free movement is restricted by COVID-19 and information in the media is a blend of fact and fiction. In the Digital Mesh, people are connected by empathy while on the other hand an invisible wall grows while feeding on hatred and animosity. Digital technology that appears to bring people together across distances might actually isolate, manage and monitor them.

The outbreak and spread of COVID-19 made me realize that we are living in such times. But I might have lived without realizing this even if COVID-19 had never occurred. We must still live in such an age even when COVID-19 subsides.

In the future, many invisible walls will continue to arise and we will face these walls repeatedly. When this happens, we must not just depend on the Digital Mesh. We must also confront these invisible walls with our bodies, and exchange expressions with respect, interest and curiosity without solely pursuing correctness or fearing discrepancies or misunderstandings. We should never give up even if we don't understand something. After all, isn't this the kind of "clumsy manners" needed for crossing borders, engaging in exchanges and harnessing the power of creation in the future?

*¹ Official YouTube channel of the Japan Cultural Institute in Cologne (the Japan Foundation)

"「壁」と戯れる/Mauerspiel"

https://youtu.be/LmwFJY_cY3M/

Related Articles

Keywords

Back Issues

- 2022.7.27 Beyond Disasters - T…

- 2022.6.20 Beyond Disasters - T…

- 2021.6. 7 Contributed Article …

- 2021.4.28 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2021.4.27 Contributed Article …

- 2021.4.20 Contributed Article …

- 2021.3.29 Contributed Article …

- 2020.12.22 Interview with the R…

- 2020.12.21 Interview with the R…

- 2020.11.13 Interview with the R…