My Relationship with the Japanese Language and Literary Translation

Yue Yuankun

PhD student, Beijing Center for Japanese Studies

It all began when I was a second year grad student. I had stumbled upon an ad looking for translators, so I applied and landed the job, and thus my career as a literary translator got underway. The first piece I translated was Tokugawa Ieyasu, which won the Noma Award for the Translation of Japanese Literature in 2011. All I can say is that it was a series of lucky coincidences for me. Since I won the award, many people have come up to me asking what inspired me to study Japanese. They probably imagine that I knew a great deal about Japan, or at least was keenly interested in Japan. But truth be told, this was not the case, and I would feel a little embarrassed, since I would have to reply each time that it was just because I had been assigned to the Japanese language program. A system of the university entrance exam in China is quite different from that in Japan; I will not go into detail here as it would be a long story, but to make it short, it was not my decision to study Japanese. Perhaps it would be more accurate to say that the Japanese language department whisked me away.

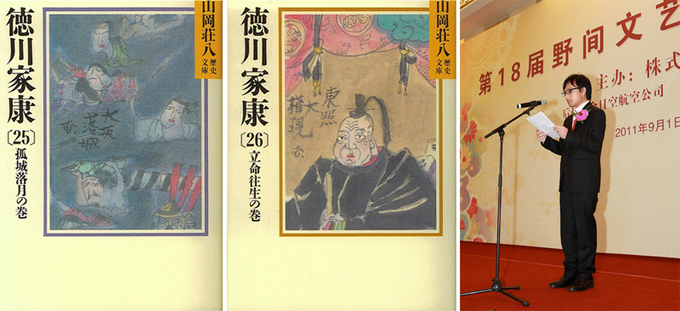

Left: Tokugawa Ieyasu Volumes 25 and 26 by Sohachi Yamaoka

Right: Award ceremony for the Noma Award for the Translation of Japanese Literature

I have adored books since I was a child and dreamt of becoming a novelist like Lu Xun when I grew up. Reading Lu Xun's The True Story of Ah Q would make me laugh, and tears would roll down my cheeks as I read Ordinary World by Lu Yao (awarded the Mao Dun Literature Prize) or the Chinese translation of The Gadfly by Ethel Lilian Voynich. In the 90s, unlike today, not many Japanese works of literature were being translated into Chinese, and even if they were translated, it was extremely unlikely that you would find them in the bookstores of isolated and rural areas in China. The history of war certainly did not help either, and so it had never even crossed my mind to study Japanese in university. I had my sights set on studying Chinese or English literature. The only Japanese novels I knew were I Am a Cat, which had been in our history books, and The Factory Ship, as an outstanding example of proletarian writing.

Just before my university entrance exam I had been reading a book called Funeral of Muslims, written by Huo Da and winner of the Mao Dun Literature Prize. One of the secondary characters in the novel was a female student who studies Russian in high school, but is assigned to the English program in university. She was a pure and sweet soul, and I felt sorry for her. As I said, I was in love with western literature and was hoping to study English in university, but as if mirroring her fate, I ended up being assigned to the Japanese program. When I learned it was impossible to change courses, the girl in the book became my source of comfort. She had gone on to overcome difficulties and managed to keep up with other students, and so it was that I made up my mind to work hard and study Japanese.

Obviously, I then started reading Japanese literature. The first time I remember feeling glad to be studying Japanese was when Botchan made me laugh or The Dancing Girl of Izu moved me.

Feelings lead to interest. I believe the reason foreign literature is translated and read by people in the first place is that, though languages and cultures may differ, there are commonalities that may be shared or felt by readers within the writing. People often think that differences in language or culture are the starting point for translation, but I believe it is the opposite--literature gets translated because of the common aspects that we share as human beings.

To be able to read and understand foreign works while in your own country is the same as being able to read and understand old classics today. This is because literature is, after all, something that describes human emotions. As long as it talks about the human heart, it does not matter whether it is old or new, domestic or from abroad; there are emotions that everyone can relate to. For example, there is a poem in the Hyakunin Isshu, "Kimigatame oshikarazarishi inochisahe nagakumoganato omoikerukana," which means "I wasn't afraid of giving my life to see you, but after I met you I would like to live longer to spend more time with you." The emotions expressed of falling in love or being in love are no different to those felt by us in the modern age. That is why these poems are still read today. I believe that even if they were translated into Chinese, they would be embraced by Chinese audiences. Though not a literary piece, My Neighbor Totoro is also popular in China because it touches Chinese audiences in the same way as it does Japanese audiences. I believe the universal aspects that defy time or space are the most important reasons why literature is translated and read.

Furthermore, if a book resonates with readers' feelings, their curiosity is aroused, and inevitably they are led to take an interest in the country the book came from. If the love poems of the aforementioned Hyakunin Isshu were translated, readers who sympathize with the poems would become curious about the poets, their world and times, and would be inspired to read further. Thus, the translation of literature contributes to furthering cultural exchange.

Obviously, the significance of literary translation does not stop there. Looking at the history of Japanese literature, we see that translations not only encourage cultural exchange, but have always stimulated domestic literature and helped it flourish. In the Heian period a thousand years ago, Chinese poems were translated into Japanese, and this brought about a new wave of Japanese waka poems. The same can be said for the Edo period. Without the translations and adaptations that came before, the famous Yomihon text Tales of Moonlight and Rain would never have existed. Thus, we can say that new forms of Japanese literature blossomed from the translation of ancient Chinese literature. In the modern age, the translation of western literature into Japanese led to the birth of brilliant modern literature in Japan. These books were then translated into Chinese and in turn had a well-known impact on Chinese literature.

Literary pieces are always an amplification and repetition of the same basic ideas, and these amplifications and repetitions generate new and wonderful work. For example, the image of young Murasakinoue seen through the eyes of Hikaru Genji in the Wakamurasaki volume of The Tale of Genji has been passed down for a thousand years to take shape as Mei in My Neighbor Totoro today. Of course, exceptional work cannot be produced through simple inward-looking repetition. New elements and ideas are required for the creation of great art. Thus, literary translation is extremely important not only in providing new material for amplification and repetition, but also in offering new ways of thinking.

At the moment, I am in the middle of writing my doctoral thesis on the literature of Akinari Ueda. I chose this theme because I became fascinated by the genre of adapted literature in graduate school, and wanted to identify its creative methods, focusing on ties with Chinese literature. In future, I hope to follow in Akinari Ueda's footsteps, and continue studying literature while doing creative work that brings together the elements of translation, adaptation, and Japanese literature. Then, I feel I would be staying true to my first aspirations to lead a career in literature.

(Originally written in Japanese)

Yue Yuankun

Yue Yuankun

Born December 1981 in Shandong Province. Graduated from the department of Japanese studies of Shandong University at Weihai in 2004 and received a master's degree in literature from the Beijing Center for Japanese Studies at the Beijing Foreign Studies University in 2007. Worked for two years at the Department of Japanese Studies, School of Foreign Languages, Tianjin University of Commerce, mainly teaching Japanese language and Japanese literature. Enrolled in the Beijing Center for Japanese Studies doctoral program in 2009, majoring in Japanese modern literature. Came to Japan in 2011 as a Japan Foundation Beijing Center for Japanese Studies doctoral fellow, and is writing a doctoral thesis at Tokyo Metropolitan University. Main translation works include Tokugawa Ieyasu (Volume 1, 10, and 13 of the Chinese translation) by Sohachi Yamaoka, Meitantei no okite, Meitantei no jubaku, and Shinzanmono by Keigo Higashino, Kamigami no itadaki (Part 1 and 2) by Baku Yumemakura, Ore no kare by Youshichi Shimada, Chihate umitsukiru made (Part 1 and 2) by Seiichi Morimura, (Keigo Higashino), and Ryoma ga yuku (Volume 1 and 2) by Ryotaro Shiba. He has also written the sections on songs and the modern novel for Japanese Literature (Part 1) by Zhang Long Mei (Higher Education Press, Beijing).

Beijing Center for Japanese Studies

Beijing Center for Japanese Studies: Mid-term Report on Study Period in Japan

Related Events

Keywords

- Literature

- Translation

- Language

- Japanese Studies

- Japanese-Language Education

- China

- Japan

- Tokugawa Ieyasu

- Noma Award for the Translation of Japanese Literature

- Lu Xun

- Lu Yao

- Ethel Lilian Voynich

- I Am a Cat

- The Factory Ship

- Funeral of Muslims

- Huo Da

- Botchan

- The Dancing Girl of Izu

- Hyakunin Isshu

- My Neighbor Totoro

- Tales of Moonlight and Rain

- The Tale of Genji

- Akinari Ueda

Back Issues

- 2025.7.31 HERALBONY's Bold Mis…

- 2024.10.25 From Study Abroad in…

- 2024.5. 2 People-to-People Exc…

- 2022.11. 1 Inner Diversity<3> <…

- 2022.9. 5 Report on the India-…

- 2022.6.24 The 48th Japan Found…

- 2022.6. 7 Beyond Disasters - …

- 2021.3.10 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2020.7.17 A Millennium of Japa…

- 2020.3.23 A Historian Interpre…