The Power of Novels Transcends National Borders

Kim Yeonsu (Novelist)

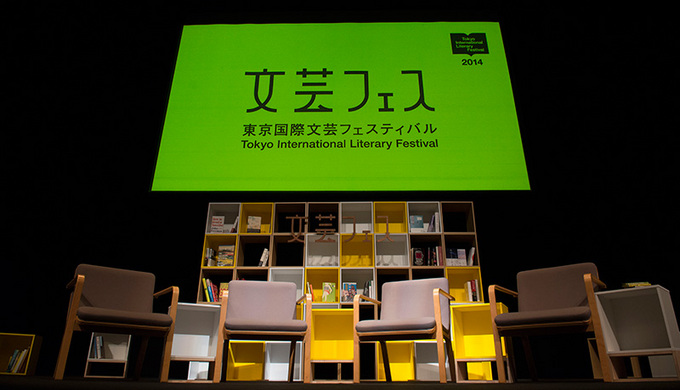

Some 20 foreign authors were invited to participate in the 2014 Tokyo International Literary Festival. The 2013 edition of the festival put the spotlight on Western authors, but this year the focus expanded to include Asian literature as well, so Asian authors were invited. In this article, South Korean novelist Kim Yeonsu, who participated in the symposium "Writing Now in Asia" organized with the special cooperation of the Japan Foundation and co-hosted by the International House of Japan, reminisces about the exchange with foreign authors at the Tokyo International Literary Festival, the dialogue with Japanese writer Keiichiro Hirano, and his encounters with Japanese literary fans.

Participation in the Tokyo International Literary Festival

On December 4, 2013, I received an email message from Kim Seung Bok of CUON Publishing, the company that published the Japanese translation of my collection of short stories, World's End Girlfriend. In the message, he explained that the Tokyo International Literary Festival would be held from February 28 through March 9, 2014, and the organizers would like to invite me to the event. I did not know that such an event was to be held in Tokyo. The email contained an attachment with a brief description of the festival. According to the explanation, it was established in February 2013, and for its first edition the organizers invited mainly Western authors, but in the second edition they planned to open its doors to the world and organize a forum for Asian authors.

I was extremely interested in this festival, because back in 2006 I participated in a similar event, the 1st Seoul Young Writers' Festival. Organized with the goal to establish a venue for cultural exchanges among young authors from all over the world, this festival attracted writers whose works are written in various languages: English, French, Spanish, oriental languages, etc. Literature is an art form best conducted in the writer's own language, so it must go through a process of written translation or oral interpretation. For the same reason, writers from different countries need the medium of translation or interpretation in order to communicate. Compared to art forms that do not require this medium, such as music and fine arts, or cinema and theater, which are only partially affected by verbal limitations, literature poses significant handicaps when it comes to international exchange of ideas. That is why I was essentially interested in what measures the organizers of the Tokyo International Literary Festival would take in order to overcome these limitations.

I said that literature faces verbal barriers, but of course I am aware that encounters between people are governed by a simultaneous interaction between verbal and nonverbal factors. This fact was confirmed by my experience at the 1st Seoul Young Writers' Festival in 2006 conducted with the participation of authors from various countries, and further reaffirmed by the East Asia Literature Forum, a biennial event launched in 2008 and hosted in turn by Korea, China, and Japan as a venue for exchange among writers from the three countries. So far, I have had numerous opportunities to meet Japanese novelists in particular, and I feel that with each encounter our mutual understanding deepens. Keiichiro Hirano, Masahiko Shimada, and Mieko Kawakami are some of the writers whom I have met several times in the past few years. I met them after reading their novels translated into Korean, and felt very relieved that the image I had concurred based on their works was not so much different from reality. At the same time, our friendship grew stronger. This process, however, was not conducted through perfect communication.

I boarded the flight to Haneda on March 5, with the Tokyo International Literary Festival well under way. After arriving in Tokyo, I learned more details of the event. As I mentioned above, the festival was established in 2013, and the organizers plan to hold it on an annual basis. In 2013, John Maxwell "J. M." Coetzee, the winner of the 2003 Nobel Prize in Literature, as well as Junot Díaz, Jonathan Safran Foer, Nicole Krauss, and other young European and American authors attended the festival and discussed literature with Japanese writers. In 2014, in addition to Junot Díaz, who was back after last year, the festival was attended by Jeffrey Eugenides, David Mitchell, and other Western writers. I was also impressed by the fact that participation was not limited to writers only, and editors of literary magazines such as the British Granta and the American The New Yorker also attended the event. "Writing Now in Asia," the program, in which I was to participate, was newly established in order to facilitate dialogue among Asian writers, departing from last year's European and American-only participation. Tash Aw, an author originally from Malaysia now living in the UK, Thai novelist Uthis Haemamool, myself, and Kyoko Nakajima of Japan participated in the discussion, and Keiichiro Hirano served as the moderator.

Kim Yeonsu

Left: Keiichiro Hirano, winner of the 120th Akutagawa Prize for the novel L'Eclipse

Right: Kyoko Nakajima, recipient of the 143rd Naoki Prize for the novel The Little House

Literary experience from the position of an outsider

The program was held on March 6, from 6:30 p.m. at the International House of Japan in Roppongi. We, the participants, began the discussion by sharing the stories that led us to becoming writers. Tash Aw talked about the complex situation in Malaysia, where multiple ethnic groups and cultures coexist, and explained how he was attracted to writing novels from the position of an outsider. The other participants could also relate to this perspective of experiencing literature from the position of an outsider, and it became the unofficial theme of the program. Uthis Haemamool spoke about his realization that "literature is an act of observing society from a position removed from the mainstream perspective," illustrating his words with the translated novels of Yukio Mishima that he read in his adolescence. I shared the fact that my literary experience was very similar to theirs, and that, paradoxically, non-mainstream literature created from the position of an outsider expands the emotional ground shared by writers and their readership.

Left: Tash Aw of Malaysia, recipient of the Whitbread and Commonwealth Prizes and the O. Henry Award

Right: Uthis Haemamool of Thailand, winner of the S.E.A. Write Award for the novel The Brotherhood of Kaeng Khoi

In Korea, and probably in Japan as well, the interest in Asian literature and perspectives is lower compared to the Western world. Still, China and Japan are our neighbors, so the Korean audience has access to a large number of translated books and is relatively well acquainted with their literary trends. But as far as the rest of Asia is concerned, the truth is that I have read very few novels even by Taiwanese writers, and knew almost nothing about the works of Southeast Asian authors from countries such as Thailand and Malaysia. This program gave me an opportunity to get in touch with Southeast Asian authors who previously were unknown to me, and listen to their stories. I also realized that, despite our different national backgrounds, there were no significant differences between their path to the literary world and my own experience. First of all, the lists of literary works that have influenced us are very similar, and the position occupied by the novel genre in our respective countries nowadays is not so different. The societies in all countries shared the concept that the fundamental virtue of novelists is precisely this endeavor to explore society from a new angle. We agreed on the fact that our identity as outsiders has fueled the spark of our creativity and imagination and eventually has led us to the literary world.

That day, we received the following question from the audience: "How can you call yourself outsiders, when mainstream magazines and newspapers publish reviews of your new works?" Tash Aw responded by sharing the experience of reading a newspaper review of his first published book. He thought that the review would be an assessment of his work, but when he reached the word "Nevertheless" at the end, he immediately closed the newspaper, and has not read another review since. This response, which made the entire audience laugh, meant that as novelists we are judged only by our work and therefore we are constantly facing the possibility of failure. Being a novelist does not automatically guarantee success. In this sense, the term "mainstream novelist" is somewhat of an oxymoron. I was very interested in his story. It reaffirmed my belief that novelists share similar experiences regardless of their nationality.

Photo courtesy of the Nippon Foundation

Dialogue between Kim Yeonsu and Keiichiro Hirano

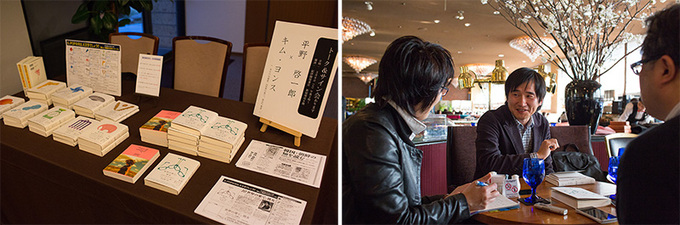

The second program in which I participated was a dialogue with Keiichiro Hirano, a novelist with whom I had kept in touch for some time. The Japanese translation of my collection of short stories World's End Girlfriend had just been published, and in order to take advantage of this timing, the dialogue was conducted in front of an audience at the Kinokuniya bookstore in Shinjuku. My relationship with Mr. Hirano dates back to 2006. A lecture was held on the occasion of his visit to Korea as part of a program conducted by the Japan Foundation, and I served as the moderator. That was our first encounter. Back then, I did not have many opportunities to meet with Japanese writers, so I was very interested in his opinions and ideas. Politically, the Japan-Korea relationship has always been tense, and back in 2006 it was not much different from today. That is why I was concerned about how a Japanese writer of my generation might see the situation, but, to my surprise, his perspective on things was not that different from mine. When we met again to participate in a dialogue published in The Hankyoreh newspaper, we did not discuss politics or history, but started our conversation with the topic of rock music. Later, I found out that our tastes in rock music were very similar. Since then, we have maintained our relationship and meet every time I visit Japan or he visits Korea. This has deepened our friendship.

While most of Keiichiro Hirano's novels have already been translated into Korean, I had only three short stories translated into Japanese. When my collection of short stories World's End Girlfriend was published in a book format, he was the person who welcomed it with the greatest joy and enthusiasm. Not only did he write a compelling and poignant endorsement for the book, but he also took upon himself the task of forging bridges that would bring my book closer to the Japanese readership, using various tools. Until now, I was deeply impressed with his selfless hospitality and warm consideration, but the word gratitude is not enough to express my feelings when I think about what he did for me this time. In the past, my experience has often taught me that literary exchange is not simply a rhetorical phrase. Initially, I had my doubts whether novelists from two countries with such different positions could possibly discuss historical and political issues, but less than 10 minutes into our first meeting I realized that my concern was unfounded. I had already read Mr. Hirano's novels, so I had an idea of his way of thinking. He, however, might have felt slightly ill at ease before my works were translated into Japanese. The reason why he helped me so selflessly when my short story collection was translated may lie in his belief that my work would deepen our mutual understanding.

From this perspective, I believe that the tenser Japan-Korea relations grow, the stronger and more extensive exchanges must be implemented. Through literature, we indirectly experience the lifestyle and value systems of foreign countries, and this exposure deepens our mutual respect for each other. I have experienced this personally. Import of Japanese popular culture was banned in Korea until the 1980s, when I was still a teenager. The Korean audience had no access to Japanese cinema, animation, TV drama serials, comics, etc. As a result, Korean people had no means of knowing the lifestyle and mentality of their Japanese neighbors. The Japanese existed only as a specific image, but this image, which was created by the mass media, was the greatest obstacle to understanding the real Japanese people. Japanese novels were translated into Korean, but the mainstream of these translations consisted of modern and popular fiction from a different age, so the readership of Japanese novels was limited to researchers and a certain group of devoted fans. In the 1990s, novels of contemporary writers such as Ryu Murakami, Haruki Murakami, Masahiko Shimada, and Banana Yoshimoto were translated, triggering a full-fledged Japanese fiction boom in Korea. I belong to a generation that has been reading Japanese novels since that period. These novels entirely changed my image of Japan's society and people. I believe that in the same period a similar transformation occurred among many Korean readers who got hooked on Japanese fiction.

The first step toward understanding is the interest and regard for others

When I visited the Kinokuniya bookstore in Shinjuku for the dialogue with Mr. Hirano, representatives of CUON Publishing took me to show the Korean novel section. Compared to the number of Japanese novels sold at the Kyobo Book Center in Seoul, the number of Korean books in Kinokuniya was rather small. I believe this number is an indicator of the level of understanding the other side. I am not saying that since we translate so many of your books into Korean, we would like to have an equivalent number of our books translated into Japanese, or that since our works are very meaningful, you should translate them with conviction even though the market response might be sluggish. I am just trying to describe the reality.

In an interview by a Japanese newspaper about the publication of my collection of short stories, I received a request to discuss the recent tension in the relations between the governments of Korea and Japan. For me, Japan is a source of numerous topics of interest, such as literature, cinema and music, or urban culture and cuisine. It appears, however, that those on the interviewing side had only two topics of interest when considering Korea: history and politics. I wonder whether their knowledge and awareness about Korea was really that poor. I am completely baffled by the preconception harbored by Japanese journalists that all Korean novelists visiting Japan have the answers to the questions about history and politics. If Japanese novelists are confused by such questions, so are Korean writers. In other words, we are not that much different.

Nevertheless, I was surprised by the passion of the Japanese audience who gathered at the venue of the dialogue. More than 50 people waited for us on the 6th floor of the Kinokuniya bookstore in Shinjuku Minami. I had some fears that they might inquire about politics or ask ordinary questions about Korean literature in general, but the readers managed to surprise me with very specific inquiries. For instance, one of the questions was "You have translated the works of Raymond Carver, so do you think translation is helpful to writing novels, and if so, in what way?" Upon hearing this question, all I could do was just to gaze intently at the face of the young man who asked it. That is because I am often asked the same question by my Korean readers. I was asked a very interesting question too. Another reader asked "The young artists who win the Kenzaburo Oe Prize are given an opportunity to have their works translated into English, so if you create literary prizes that bear your names, what kind of an extra prize would you offer?" Mr. Hirano responded that he had no intention of creating a literary prize with his name, and his answer completely matched my opinion on the subject, which surprised me a bit. Still, since Mr. Hirano responded first, I had to come up with a different answer. Any language or cultural barriers disappeared in the lively and energetic exchange of questions and answers.

In my explanation, I reversed the order of the discussion. In the beginning of the dialogue, Mr. Hirano shared an episode of his visit to Korea and explained the long-lasting interest of Korean readers toward his work. In 2005, when I visited Japan and conducted a lecture upon an invitation by the Japan Foundation, virtually no one in the audience knew anything about Korean literature or about me, so I exhausted a large amount of time in my self-introduction and explaining in general the Korean literature and the position of my novels in it. This time, however, Mr. Hirano, with whom I have a long relationship, introduced me from his own perspective, so I think I succeeded in getting closer to the Japanese readership. Also, compared to the audience eight years ago, the people I encountered this time created the impression of true readers. Even after the end of the discussion, they came up to us to ask questions, and demonstrated strong interest in our literary works. Also, I noticed that, compared to the situation eight years ago, the number of people who speak Korean has increased. In the past, I was addressed in Korean almost exclusively by fellow countrymen living in Japan. I felt that, little by little, the interest in Korea is shifting to Korean literature. This is an extremely positive phenomenon. We are witnessing the beginning of a trend similar to the developments in my country, when the Korean people began reading Japanese novels and as a result the prejudice toward the Japanese people and culture gradually declined. The fact that I visited Tokyo for the first time in eight years on an occasion as trivial as the first publication of my translated work, and was inspired that much, illustrates the significance of the changes that have taken place during these eight years.

The participation in the Tokyo International Literary Festival and the opportunity to discuss literature with fellow writers from various Asian countries was an extremely gratifying and interesting experience. I managed to reassert the fact that, when trying to understand differences and confirm common points through dialogue, novels are a valuable tool that is not limited within the borders of a single country, but transcends national borders and aims to attain universal values for the entire humankind. A large audience filled the venue in order to listen to what the writers had to say. Looking at the sparkling eyes of the members of the audience as they listened intently to the words of writers from foreign countries, I felt the true power of the novel genre. The first step toward understanding is the interest in others. Novels always describe the life of others. The life story of other people, unfamiliar scenery, far-away countries... I have always considered novels the best possible tool to deepen our understanding of strangers because when we read a novel, we identify ourselves with strangers and experience first-hand their life story. In that sense, I hope that both in Japan and in Korea, more foreign novels are translated and more people are willing to read them.

Photos courtesy of CUON Publishing ("Kim Yeonsu × Keiichiro Hirano: Dialogue")

Kim Yeonsu

Kim Yeonsu

Kim Yeonsu was born in Kimcheon, Kyeongsangbuk-do in 1970. He graduated from the Department of English Language and Literature of Sungkyunkwan University (SKKU). Kim made his debut in 1993 with a poem in the journal Jakka Segye (Writer's World). The following year, he published a novel I Wear a Mask, which was met with critical acclaim. In 2001, Kim won the S.E.A. Write Award for his novel Good Bye Lee Sang. In 2003, he was distinguished with the Dong-in Literary Award for the novel When I was Still a Child. In 2005, his novel I am a Ghostwriter won the Daesan Literary Award. In 2007, Kim received the Hwang Sun-won Literary Award for the short story The Comedian Who Went to the Moon, stepping into the spotlight as a writer of a new generation. In 2009, he won the Yi Sang Literary Award, one of Korea's most prestigious literary awards, with Five Pleasures for Those Who Take Walks. Kim is recognized as one of the driving forces of modern Korean literature. At the same time he is a popular writer who garners fervent support from the younger generations. Apart from novels, he has written the essays The Writings of Youth, The Right to Travel, and The Moments We Spent Together. Together with Kim Junghyuk, he co-authored Someday Soon Happy End. These works have created a large base of loyal readers.

Keywords

- Anime/Manga

- Film

- Translation

- Music

- International Exhibition

- Republic of Korea

- Taiwan

- China

- Japan

- Thailand

- Malaysia

- United States

- U.K.

- Tokyo International Literary Festival

- International House of Japan

- Keiichiro Hirano

- CUON Publishing

- Seoul Young Writers' Festival

- Masahiko Shimada

- Mieko Kawakami

- J. M. Coetzee

- Junot Díaz

- Jonathan Safran Foer

- Nicole Krauss

- Jeffrey Eugenides

- David Mitchell

- Granta

- the New Yorker

- Tash Aw

- Uthis Haemamool

- Kyoko Nakajima

- Yukio Mishima

- Kinokuniya Bookstores

- The Hankyoreh

- Ryu Murakami

- Haruki Murakami

- and Banana Yoshimoto

- Kyobo Book Center

- Raymond Carver

- Kenzaburo Oe

Back Issues

- 2025.7.31 HERALBONY's Bold Mis…

- 2024.10.25 From Study Abroad in…

- 2024.5. 2 People-to-People Exc…

- 2022.11. 1 Inner Diversity<3> <…

- 2022.9. 5 Report on the India-…

- 2022.6.24 The 48th Japan Found…

- 2022.6. 7 Beyond Disasters - …

- 2021.3.10 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2020.7.17 A Millennium of Japa…

- 2020.3.23 A Historian Interpre…