6. Reading The Buddha in the Attic (Part 1)

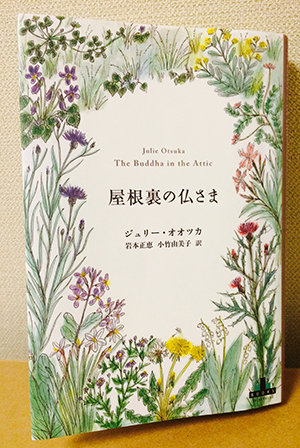

The Buddha in the Attic (Vintage Books, 2011; the Japanese edition published by Shinchosha, 2016) by Julie Otsuka hit the bookstores in late March this year, and became a critically acclaimed hit immediately after its publication.

In mid-April, carefree and clueless, I entered a bookstore and impulsively picked up the book, lured by the pretty flowers on its cover. But the moment I turned the first page, I was captivated.

"On the boat, we often wondered: Would we like them? Would we love them? Would we recognize them from their pictures when we first saw them on the dock?"

(From The Buddha in the Attic)

"We" are the protagonists of The Buddha in the Attic. Using this slightly unusual "first-person plural" narrative, Julie Otsuka brings to life the voices of the so-called "picture brides," young Japanese women who traveled to the U.S. at the beginning of the 20th century.

I just described them as "Japanese women," but they all came from different parts of Japan.

Some were from Kyoto and were "delicate and fair," having lived their "entire lives in darkened rooms at the back of the house," others were "farmers' daughters from Yamaguchi" or "from a small mountain hamlet in Yamanashi," yet others were born and raised in Hokkaido, "where it was snowy and cold." The women from Tokyo, who "had seen everything, and spoke beautiful Japanese" perhaps believed themselves different from the rest and so "pretended" they could not understand "the thick southern dialect" spoken by the women from Kagoshima. These women from all over Japan, who traveled across the Pacific Ocean, did not consider the Okinawan they met in the U.S. to be "real Japanese."

These countless women from different backgrounds and with different experiences, appearances, ambitions, misfortunes, and hopes, are "us," the protagonists who tell their stories in The Buddha in the Attic.

The Japanese edition of The Buddha in the Attic by Japanese-American author Julie Otsuka. The pretty flowers depicted on the cover of the book lured me into picking it up, but the story captivated me from the very first page.

As I eagerly followed the rhythmical flow of the prose, countless sequences materialized before my eyes and disappeared, re-appeared and then faded away. I felt like I was watching a series of trailers for short movies.

I was particularly impressed by the chapter entitled "The Children."

"One by one all the old words we had taught them began to disappear from their heads. They forgot the names of the flowers in Japanese. They forgot the names of the colors. [...] They spent their days now living in the new language, whose twenty-six letters still eluded us even though we had been in America for years. All I learned was the letter x so I could sign my name at the bank. They pronounced their l's and r's with ease. And even when we sent them to the Buddhist church on Saturdays to study Japanese they did not learn a thing. [...] But whenever we heard them talking out loud in their sleep the words that came out of their mouths came out--we were sure of it--in Japanese."

(From The Buddha in the Attic)

Japanese. The language of the children's mothers, "us," the protagonists of the story.

They must have nursed the babies, who in a few short years would "pronounce their l's and r's with ease," caressed them and gently whispered in Japanese, yoshi, yoshi (there, there) or orikō-san (good boy/girl).

Born and raised in the U.S., a foreign country, their children must have called the women "Mom," or "Mommy," but when the women remembered their own mothers whom they left behind in Japan, the words that first came to mind must have been "okkā" (a spoken word for mother, used by lower and middle class people), or "okāsan" ("mother" in Japanese).

Japanese was the language of "our" (the protagonists') okāsan.

Raised in the U.S., the children were gradually distancing themselves from all things Japanese that their "moms" and "mommies" had received from their "okāsan."

"They gave themselves new names we had not chosen for them and could barely pronounce. One called herself Doris. One called herself Peggy. Many called themselves George. [...] Etsuko was given the name Esther by her teacher, Mr. Slater, on her first day of school. 'It's his mother's name,' she explained. To which we replied, 'So is yours.'"

(From The Buddha in the Attic)

"Our" children were willing to discard the names of their mothers' mothers in order to acquire more American-like names.

As I was reading the story, I subconsciously superimposed myself, a girl with a Taiwanese mother raised in Japan, onto the image of these children. There were times when I wished my name was Yumiko, or Yuko, or something else more Japanese-like, instead of Yuju.

"Sumire called herself Violet. Shizuko was Sugar. Makoto was just Mac. Shigeharu Takagi joined the Baptist church at the age of nine and changed his name to Paul."

(From The Buddha in the Attic)

The children who changed their names to Violet, Sugar, Mac, and Paul did not understand the language of their grandmothers in Japan, the homeland of their mothers.

Unlike me, I thought.

I understand my obāchan's (granny's) language very well.

In my case, I forgot my mother's language, but in exchange I learned the language of my obāchan.

As a national of the Republic of China, my mother, a Taiwanese, learned Chinese, but my grandmother, who spent her childhood in Taiwan under Japanese rule, learned not Chinese but Japanese.

The book turned my thoughts to this history, and I felt that the voices of the women in the U.S. who just could not forget Japanese as the language of their homeland suddenly mixed with the voices of the women in Taiwan who had to learn Japanese as the language of their suzerain country. This feeling made me dizzy.

Books I bought in the past, when I wanted to explore the way of expressing Japanese from the perspective of Americans of Japanese descent and Chinese and Taiwanese from the perspective of Taiwanese migrants in the U.S. Asian American Literature: An Introduction to the Writings and Their Social Context (Elaine H. Kim, Temple University Press, 1982; the Japanese edition published by Sekaishisosha, 2002) and Ajia-kei Amerika-bungaku wo Manabu Hito no Tame ni [For Those Who Study Asian American Literature] (by Sekaishisosha, 2011).

Julie Otsuka, an American of Japanese descent, wrote in English, her native tongue, a book that tells the stories of Japanese women from the generation of her grandmother and great-grandmother, whose native tongue was Japanese. Her book was then translated into Japanese, and I, a Taiwanese national raised with the Japanese language, am now reading it. And not just reading it, but mixing the voices of the nameless Japanese who traveled to the U.S. with those of the Taiwanese people who lived under Japanese colonization rule. Reading The Buddha in the Attic was a truly priceless experience for me.

Soon after that, I received an unexpected e-mail message that got me rubbing my eyes in disbelief. "Is this a dream?"

The e-mail was a request to participate in a talk about The Buddha in the Attic with one of the translators of the book, Yumiko Kotake.

In the very next moment, I was already typing my response with trembling, no, rather dancing fingers. "I'd love to!"

(To be continued in Part 2)

Keywords

Back Issues

- 2022.7.27 Beyond Disasters - T…

- 2022.6.20 Beyond Disasters - T…

- 2021.6. 7 Contributed Article …

- 2021.4.28 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2021.4.27 Contributed Article …

- 2021.4.20 Contributed Article …

- 2021.3.29 Contributed Article …

- 2020.12.22 Interview with the R…

- 2020.12.21 Interview with the R…

- 2020.11.13 Interview with the R…