005 種を植え、木になる過程を追う。それがアートになる。

プラープダー・ユン

小説家・アーティスト

フィリピン人とタイ人の外見が似ているというのは、やや時代遅れな考え方だと思うし、私としては一般的に似ていないと思うのだが、外国人からは混同されがちだといって間違いないだろう。少なくとも自分にとって、さらに興味深いのは、フィリピンはアジアに属し、フィリピン人はアジアの人種なのに、その文化は、タイはもちろんのこと、典型的なアジア文化についてのイメージと大いに違うということである。その理由は、私のフィリピンの友人たちが好んでいうところによると、彼らは自分たちのことをアメリカ人だと思っているスペイン人だからだ。フィリピンは300年以上にわたり、スペインの植民地だったし、米西戦争と米比戦争のあと、アメリカ主義が台頭した。その効果は永久的なものだったようだ。マニラやセブといったフィリピンの大都市にいると、バンコクや北京、東京といった都市よりも、カリフォルニアやフロリダにいるのに近い感じを覚えるものだ。

アメリカの影響というものは、もはや空気中にあるような存在で、世界のどれだけ辺鄙な場所でも見られるようになったけれど、かといって多くの土地では、人々が自分のことをアメリカ人だと思っているわけではない。アメリカの物質主義を支持し、アメリカのジャンク・フードなしで生きることができなかったり、ハリウッドのヒット作品を切望し、アメリカのアイコンを崇拝しても、自分には別のアイデンティティがあると思うだろう。こういった人のなかには、アメリカを嫌悪する人だっている。ミッキー・マウスを愛しても、ウォルト・ディズニーは忌み嫌うというように。マニラやセブでは、こういう感覚はない。フィリピンのエリートや支配階級の人々は、あたかもアメリカにいるかのように振る舞う。実のところ、彼らは「母国」を頻繁に訪ねる。有名な作家であるフィリピン人の友人が、一度、この傾向はフィリピンの現代社会における典型的なコンプレックスだと認めたことがあった。「(フィリピン人は)アジアのほうは決して見ないんだ」と彼は言っていた。「国の外を見るときは、アメリカだけを見るんだ」と。

2002年に初めてフィリピンを訪れたとき、そしてそのあと何度か訪問したときは、マニラだけに滞在した。当然、そこで見たり、感じたりしたのは、アメリカ複合産業の産物だけだった。その内にあるものに近づいたのは、2009年になってのことだった。近づきたいと思った理由は? フィリピンを知りたいと思った目的はなんだったんだろう? 正直なところ、その答えはわからない。フィリピンを訪ねた何年かの間にできた友達のグループ以外、フィリピンとのコネクションはまったくなかった。それなのに再訪するチャンスができるたびに飛びついてきた。もしかしたら、アジアの他の国とはまったく違う感じに惹かれたのかもしれないし、その感覚の理由を見極めたかったのかもしれない。外見は自国の人々に外近いのに、アメリカ人のように振る舞う人々に囲まれるのがおもしろかったからかもしれない。

理由がなんだったとしても、そのおかげでフィリピンのことはまったく違う目で見るようになったし、以来、かの国のことを考えるとき、アメリカ複合産業体の存在は、自分にとって何の意味も持たなくなった。2009年と2010年にかけて、計4ヶ月にわたり、フィリピン中を旅し、地方の、そして田舎の街に滞在したり、何千もある島のいくつかに渡ったりした。台風の猛威にさらされ、何週間にもわたって屋内に閉じ込められることがどういうことか、身をもって体験した。活火山、死火山あわせて、いくつもの火山に冒険のような旅をもした。強い雨のなか、エアバスでマニラからミンダナオまで飛行し、安全に着陸したときには、どうやって自分がその旅を生き抜けられたのかを考えた。要約すると、そのときのフィリピン滞在は、ときには心臓が止まるかのようなこともあったけれど、それも含めて自分を開眼させてくれる旅だった。そこには、時々ホテルの部屋で見たアメリカのテレビ番組を除けば、アメリカ的な要素はまったくなかった。

この旅のなかで、もっとも興味深い出会いのひとつが(そんな出会いはいくつもあったということは言っておきたい)、ダバオのリック・オベンザという名前の美術教師との出会いだった。アートと自然の関係について、何人かのアーティストにインタビューしようと思ってミンダナオに行ったときのことだ。オベンザと会う前に何人かのアーティスト、ミュージシャン、文筆家などと会って、フィリピンのクリエティブなコミュニティの心理に、自然が占めている部分が大きいことに驚いていた。リサーチ目的の旅だったが、実際に訪れる前は、正反対の結果を予想していたのだ。アーティストたちが、アメリカ人のように、ポストモダン理論や、コンセプチュアルな専門用語を使って話をすると思っていた。実際、この予想は、これ以上ないというほど間違っていた。私が会った人たちはほとんど全員が、自然について、きわめてクリアで明瞭な洞察をもっていて、それを共有してくれた。そのうちの一人の有名ミュージシャンは、地球に生きる生命体すべてがどう相互に関わりあっているかということを示すために作った、ドローイングや図のコレクションを見せてくれた。フィリピンではリサーチに苦労するだろうと思っていたが、とても簡単だということがわかった。誰もが、自分の人生や仕事において、自然の存在についてどう感じているかについて、理解していたからだ。

それでもリック・オベンザのような方法で、自然についての感情を表現した人はいなかった。年の頃は50歳くらいに見え、ダバオの小学校で美術を教えているといい、有名なアーティストではなかった。フィリピンでリサーチのためにインタビューした人たちに比べて、リックは完全に無名の存在だった。謙虚な態度をした地元のアクティビストだったが、彼の生き方や教え方自体がアートのように見えた。

Ric Obenza, activist, teacher, artist

最初に会ったのは、カフェだったのだが、私のリクエストに疑いを持っているようだった。口数は少なく、彼の答えはよそよそしく、取り繕った感じだった。後になってから、待ち合わせ場所が彼には都会的すぎて、また遠い場所だったために、彼を落ち着かない、気まずい気分にさせてしまったのだと気がついた。1時間ほどにわたり、オベンザから短い、また曖昧な答えを聞いたあと、彼との会話の内容は使えないと考えた。けれども、私のほうで言うべきことがなくなったあと、彼は、私が彼の自宅を翌日訪ねることを提案した。「ドローイングとペインティングをお見せして、僕の山にお連れしましょう」と言うのだ。冗談かと思ったけれど本当だった。リック・オベンザは山を所有しており、文字通り、彼の真のアートが生きるのは、そこだけだったのだ。

Ric Obenzaís Mountain

Ric Obenzaís painting

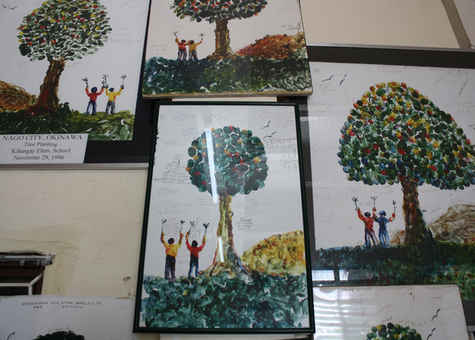

オベンザに2度目に会った時、気がついたら彼と、彼の登山用の杖の後を、高い木々や大きな根、巨大な岩石の合間を縫って登っていた。観光客のためのトレッキングではなく、本格的な登山だった。本物の森林を抜け、本物の山を登る旅で、用意されたカジュアルなエコ休暇という設定ではなかった。途中、自分が何をしているのか、なぜほとんど知らない人物が、どこか遠くの危険な場所深くに自分を誘導しているのかを自問した。フィリピンを旅している最中に、何度か突然「これがその瞬間に違いない。ここで私の死体が発見されるのだ。私の短い人生はここで終わるのだ」という思いにとらわれることがあった。リック・オベンザの山でも、同じことを考えそうになったが、思いとどまった。頂上に近づいたとき、オベンザがアートと自然、そして人生について語り始めた。この体験は、他人と一緒に歩くという行為をした経験のなかで、もっともインスピレーションを受けたもののひとつだった。彼は、私にしたのと同様に、生徒達を連れて山に上る。そして頂上にたどりつくと、生徒たちはひとりひとり彼がキャンプのなかに持っている庭園に種を植えるのだという。自分たちの埋めた種の世話をするよう指導し、彼らが木が育つ過程を描けるように、定期的に山を訪れる。「子供たちに自然について教え、人間は地球をいたわるべきだということを教えるために、この地球上の生命にどう責任を持つべきかということを示すことが、私の流儀です。自分の木を持っていれば、自然は生きていて、自己中心的な目的のために木を切り倒すべきではないということを理解する」というのだ。なかには卒業して大人になってから、教わった教訓と種について感謝しに戻ってくる生徒もいるとオベンザは言った。それをオベンザは成功と考えていた。「アートというものは、自然から何かを学んだときに発生するものです」と、オベンザは言った。彼の言ったことは、どちらかといえば曖昧ではあったけれど、私の心のなかで、数え切れないほどの熟考の瞬間のきっかけとなった。アートというものは、人が作ったり、人が見たりするものではなく、制作のプロセスのなかでなんとか培えるものなのかもしれない。山々、ミュージアム、ギャラリー・・・もっとも重要なのは、体験のあとに心に残すもので、実際にその環境のなかで見たり触れたりするものではないのかもしれない。

Following Ric Obenza up to his camp

Obenzaís studentsí paintings on the classroom wall

Obenza's students' paintings

ついに頂上にたどり着いたとき、オベンザは、私をまっすぐ自分のキャンプにある菜園に連れていってくれた。彼は声にプライドをにじませて言った。「教えたり、自然と共同作業をする何年もの生活のなかで、重要な秘密をひとつ学んだんです」。私は、人生、アート、そして宇宙について、衝撃的な格言を聞く覚悟をしていたが、オベンザは笑って、小さな植物に手を伸ばした。枝から赤いチリ・ペッパーをつまみとると、そのまま口に入れて、熱心に噛み始めた。「チリ・ペッパーは、最良の薬です。生で食べることを習慣にすると、二度と病気になりません」。

彼がひとつ手渡してくれたので、勇敢なところを見せようと、すぐに同じように口に入れてみた。舌が焼け、目に涙がたまったが、笑顔でい続けた。リック・オベンザの知恵は、アートについてのものではなかったが、チリ・ペッパーについての彼の発見が、アートと人生、そして自然の相互関係が何を意味しているのかを示しているのだった。

005 You Plant A Seed, You Watch Your Seed Becomes A Tree, You've Made Art

It's somewhat of a cliche to say that Filipinos and Thais look alike--and I think they generally don't--but it's fair to say that the two do commonly get mistaken for one another by foreigners. More intriguing, for me at least, is the fact that while the Philippines obviously belongs in Asia, and its peoples are of the Asian race, the country's culture is vastly different from the typical perceptions of "Asian," let alone Thai. Perhaps it's because, as my Filipino friends like to say, Filipinos are Spaniards who see themselves as Americans. The Philippines were colonized by Spain for over 300 years, then after the Spanish-American War and the Philippine-American War popular Americanism took over. The effect seems to be permanent. Being in big Philippine cities such as Manila or Cebu feels more like being in California and Florida than being in Bangkok, Beijing, or Tokyo.

Yes, Americanism is now close to being airborne, evident even in obscure corners of the world, but in most places the people don't necessarily see themselves as Americans. They endorse American materialism, can't live without American junk food, crave Hollywood blockbusters, and worship American icons, yet they also see themselves as having a separate identity. Some of these people even hate America; they adore Micky Mouse but despise Walt Disney. That's not the feeling one gets in Manila or Cebu. The Filipino elites and ruling classes behave as if they're in America. Indeed they frequently visit their "motherland." A Filipino friend, a well known writer, admits to me once that this is a typical complex of modern Philippine society. "We never look to Asia," he said. "When we look out, we see only the United States."

When I visited the Philippines for the first time in 2002, and several times after that, I stayed only in Manila. Naturally, all I saw and felt there was the product of that American complex. It was only in 2009 that I was able to get closer to what lied within. Why did I want to get closer? What was my objective for getting to know the Philippines? Frankly, I have no answers. Apart from a group of friends I've made over the years from my visits, I have no other connections to the Philippines whatsoever. Yet whenever I had the chance to return, I grabbed it. Perhaps because I was always fascinated by how different it felt from being in other Asian countries. Perhaps I wanted to find out why it felt that way. Perhaps it was just interesting to be surrounded by people who looked similar to the people in my own country but who acted as if they were Americans.

Whatever the reason, I now see the Philippines in a completely different light, and its American complex no longer means anything to me when I think about the place. In 2009 and 2010, for a total of about 4 months, I traveled across that country, stayed in local and rural towns, and sailed to several of its thousands of islands. I experienced how it was to be trapped indoors for weeks during a typhoon attack. I made long, adventurous trips to volcanoes, both active and dead ones. I flew on an airbus in a heavy storm from Manila to Mindanao, and when the craft safely landed I couldn't help but wonder how it was possible that I survived. To sum it up, my stay in the Philippines this time was an eye-opening, at times almost heart-stopping, journey. There was never anything American about any of it, except maybe for the occasional American cable TV programs I watched in hotel rooms.

One of the most interesting encounters (there were a lot more than one, believe me) I had in that time was with an art teacher in Davao named Ric Obenza. I went to Mindanao hoping to interview some artists about their views on the relationship between art and nature. I had talked with a number of artists, musicians, and writers before I met Obenza, and I was surprised how much "nature" there was in the general psyche of the Filipino creative community. Before I arrived in the country for the research, I'd expected to find the opposite; I thought the artists would all talk postmodern theories and conceptual jargon, the way they did in America. I couldn't be more wrong. Almost all the people I met had very clear and articulate insights about nature to share. One of them, a popular musician, even showed me a collection of elaborate drawings and diagrams he made to show how all lives on this earth were interconnected. I'd thought I would have a hard time with my research in the Philippines, but it turned out to be so easy. Everyone knew how he or she felt about the presence of nature in his or her life and work.

But no one expressed his thoughts on nature to me quite the way Ric Obenza did. Obenza, a man that looks to be in his 50s, teaches at an elementary school in Davao, and he's not a famous artist. Compared to the rest of the people I interviewed in the Philippines for my research, Ric Obenza was a complete unknown. He's just a modest, local activist, yet the way he lives and teaches seems to me to be a work of art in itself.

The first time I met him was at a cafe and he seemed suspicious of my request. He spoke little, his answers distant and forced. I later realized that the meeting place must have been too urban, too alien for him, making him uncomfortable and nervous. After an hour or so of getting only short, vague replies from Obenza, I thought my conversation with him would end up unusable. But when I ran out of things to say, he suggested that I come over to his house the next day. He said, "First I'll show you my drawings and paintings, then I'll take you to my mountain." I thought he was joking, but it was true. Ric Obenza owns a mountain, and that's where his true art comes to life, literally.

The second time I met Obenza, I soon found myself following him, and his climbing stick, up a hill through tall trees, large roots, and giant rocks. It was a real climb, not a tourist trekking trip. It was through a real forest, up a real mountain, not just some prepared, casual eco-vacation setting. At one point I asked myself what I was doing and why was I letting a man I barely knew lead me deep into a remote and dangerous place. There were many moments in the Philippines when I suddenly thought, "This must be it. This is where my body will be discovered. This is where my short life will end." I almost had that thought on Ric Obenza's mountain too, but only almost. When we neared the mountaintop, Obenza started to talk art, nature, and life. It was among the most inspiring walks I'd taken with anyone. He said that he would bring his students up to this mountain the same way he was now taking me, then when they reached his camp up top each student would plant a seed in his garden. He would tell them to take care of their own seeds, and he would bring them back regularly to paint their own trees as they grew. "My way to teach children about nature, about how we should be kind to the earth, is to show them that they're all responsible for life on the planet. If they have they own trees, they will understand that nature is alive, that they should not cut down trees for selfish purposes." Obenza told me that some students, after they'd left school and grown up, would return to thank him for his lesson, for his seeds. That's what Obenza counts as his success. "Art happens when you learn something from nature," he said. It's a rather vague statement, but one that triggers countless moments of contemplation in my mind. Perhaps art is not what one makes or what one sees, but what one manages to cultivate from the process of art making. Mountains, museums, or galleries, what matters most may be what one keeps within after the experience, not what one saw or touched in the environments.

When we finally reached the top, Obenza took me straight to a vegetable garden at his camp. "You know," he said with a hint of pride in his voice, "I learned one important secret from all these years of teaching and working with nature." I was ready for some kind of mind-blowing wisdom about life, art, and the universe. Obenza smiled and reached out to a small plant. He nipped a small red chilly pepper off its branch and put it in his mouth whole, then started to chew enthusiastically. "I've learned that chilly peppers are the best remedy. Make a habit of eating it fresh all the time and you won't ever get sick again."

He handed me one and I quickly put it in my mouth the same way he did, to show off my bravery. It burned my tongue, and tears formed in my eyes, but I kept on smiling. Ric Obenza's wisdom is not exactly about art, but perhaps his discovery about chilly peppers is what interconnection between art, life, and nature really means.

プラープダー・ユン

プラープダー・ユン

1973年生まれ、バンコクに拠点を置くタイの小説家・アーティスト。

多数の小説、短編小説やエッセイのコレクションを出版し、「ライ麦畑でつかまえて」「時計じかけのオレンジ」のような現代英語の古典文学もタイ語に翻訳。2002年に、彼の短編小説のコレクション「存在のあり得た可能性(英題:Probability)」で、タイで最も権威ある東南アジア文学賞を受賞。 他、プラープダーは定期的に日本で雑誌に執筆したり、アートのエキシビションを開催。また、映画「地球で最後のふたり」「インビジブル・ウェーブ」(主演:浅野忠信)の脚本や、現代アーティスト名和晃平の様々なアートプロジェクトにも協力。最新の小説は「パンダ」

Prabda Yoon

Born in 1973, a Thai writer and publisher based in Bangkok. He has published numerous novels, short story collections, and essay collections. In addition, he has also translated modern English-language classic literature such as The Catcher in the Rye and A Clockwork Orange into Thai. In 2002, his short story collection, Kwam Na Ja Pen (English: Probability), won the SEA Write Award.

Apart from working in Thailand, Prabda has regularly written for Japanese magazines and exhibited artworks in Japan. He has written 2 screenplays for films starring Tadanobu Asano and he is presently collaborating on various art projects with Japanese contemporary artist Kohei Nawa. His literary works have been translated into Japanese, of which the most recent is the novel Panda.