African Film Across Borders: Building New Bridges of Cooperation (Vol. 2)

My Encounter with African Films—An Interview with Sato Tadao (film critic)

2020.2.3

Interviewer: Ishizaka Kenji

Programming director, Tokyo International Film Festival

Professor/Dean, Japan Institute of the Moving Image

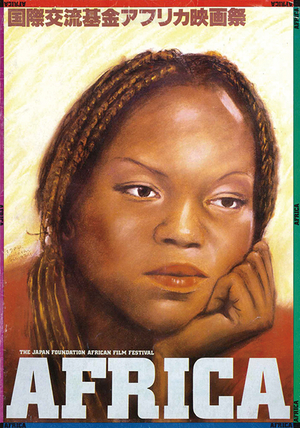

The Japan Foundation African Film Festival held in 1984 was the first such festival in Japan to feature African films. You served as chairperson of this film festival.

“A Panorama of South Asian Films” held in 1982 proved to be a far bigger success than initially imagined. It was natural for the Japan Foundation to come up with the idea to build on this success and continue doing something in this field. When we thought about what were probably the least-screened films in Japan, African films immediately came to mind. Nonetheless, nobody had much confidence about this idea back then and wondered how many African films we could even find.

Press conference for the Japan Foundation African Film Festival

You were also involved in selecting the films to be screened.

We divided into two groups. Shirai Yoshio, former editor-in-chief of the film magazine Kinema Junpo, was in charge of North Africa that covered countries north of the Sahara. I covered Sub-Saharan Africa to the south. The Japan Foundation's Paris Office (now the Maison de la Culture du Japon) handled preparatory surveys, which was why I first flew to Paris rather than to Africa. Topical or controversial works were screened in former colonial power Paris or Berlin. The French Ministry of Foreign Affairs has a library of African movies and we were given private screenings of notable works. Just around that time, Ceddo (1976), directed by Senegal's Sembène Ousmane, was playing at theaters in Paris. When I saw this film, I was amazed at its level of sophistication and immediately decided to include this film in the African Film Festival. Then we found out Iwanami Hall was purchasing the right to screen this film in Japan, so we opted out.

Even though I was able to watch a good number of movies through government agencies of the former colonial powers, I thought that it was still important to get a close-up look locally so I visited the four Western African countries of Senegal, Ivory Coast, Ghana and Nigeria. The persons I met from the African film industry were refined, courteous and business-like. They had studied films in Paris and other places, and were highly trained and well versed in film festival screenings and cultural exchanges.

My first meeting with Sembène was quite memorable because he started out talking about money. He said that if we were to screen African movies in Tokyo, then he wanted us to pay a commensurate amount for the screening. Even though we emphasized it was for the purpose of cultural exchange, he noted Japan profited as part of its economic conquest of Africa. His thinking was that Africans shouldn't be happy just because its films were screened in developed countries as this meant that Africa would be only exploited. I could also see his pride that he probably was the only person in the African film industry who could handle such tough negotiations. I remember thinking to myself that he was pretty bold and blunt, but he also had a good understanding of how things worked.

Ten films were screened at the African Film Festival. Guests were invited to Japan and a symposium was held. Kicking off with a screening at Yakult Hall in Shinbashi, Tokyo, the festival featured screenings at around 25 locations nationwide through 1985.

I believe we were able to bring together a collection of high-quality films. However, there were times when we had no idea how to position these films and we were completely trying to find our way. This was truly a novel experience. This event received considerable acclaim as a film festival although not on the same level as for A Panorama of South Asian Films.

Catalogue for the Japan Foundation African Film Festival (cover design: Awazu Kiyoshi)

Symposium at the Japan Foundation African Film Festival

Naturally, African films in actuality are extremely diverse and cinematic trends differ greatly depending on the region. It is also difficult to categorize films by country.

When I asked Sembène, he didn't mention the name of his country, Senegal. Instead, he said his are Wölöf-language films because that was his identity and he wanted to make films in the local language that his own mother would understand.

In other words, the mother tongue in the true sense.

Sembène was recognized for writing novels in French, but his own mother cannot read them. This means his books became objects foreign to the persons he really wanted to communicate something to. This is why he creates Wölöf-language films. Speaking of which, when I travelled to Senegal, I also visited Sembène's home. At the entrance, the words of the country's president was displayed. I was told that then President Léopold Sédar Senghor complained that the title of the movie Ceddo was misspelled and thus screenings of the movie were banned in Senegal. The words at his entrance were what the president said at that time. I suppose Sembène displayed them to emphasize that he is different from the president, and that he was not making a Senegalese film but a film in the local language. I'm not sure whether this is because this kind of thinking was widespread among the African firmmakers people in the African film industry or because Sembène possessed cutting-edge and clear ideas.

One characteristic of Sembène's films is style without style. Not only Sembène's works but also African films in general contain both the sophistication gained through the West and the indigenous ruggedness, and it always makes me wonder which attributes I should base my evaluation on. It makes me contemplate the appropriateness of such dichotomy.

Sembène emphasized that he knew how films in the West are made. When I asked what was the African element of his films, he said maternal love, which is a shared moral throughout Africa. I thought to myself, “Isn't it universal?” but he was adamant. Iwanami Hall screened the Sembène films Emitaï (1971) the same year as the African Film Festival, Ceddo in 1989 and relatively recently Moolaadé (2004). Takano Etsuko of Iwanami Hall wanted to screen all of Sembène's films the same as she did for films by Andrzej Wajda and Satyajit Ray. However, in Tokyo this would have been difficult from a business perspective and this screening was never fulfilled. Since the 1990s, I've been proactively involved in introducing Asian films at the Focus on Asia Fukuoka International Film Festival. Although I've become distanced from Africa, being able to meet Sembène and others still stands as a great experience.

Editing: Nakamura Daigo

Interviewed on July 31, 2019

This is a reprinted article from the side book A CENTURY OF AFRICAN FILM (published by the Japan Foundation) distributed to visitors at the symposium African Film Across Borders: Building New Bridges of Cooperation (August 29, 2019).

Related Articles

Back Issues

- 2022.7.27 Beyond Disasters - T…

- 2022.6.20 Beyond Disasters - T…

- 2021.6. 7 Contributed Article …

- 2021.4.28 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2021.4.27 Contributed Article …

- 2021.4.20 Contributed Article …

- 2021.3.29 Contributed Article …

- 2020.12.22 Interview with the R…

- 2020.12.21 Interview with the R…

- 2020.11.13 Interview with the R…