China Becomes the World's Top-Ranking Nation of Japanese-language Learning

Takeji Yoshikawa (Director, The Japan Foundation, Beijing)

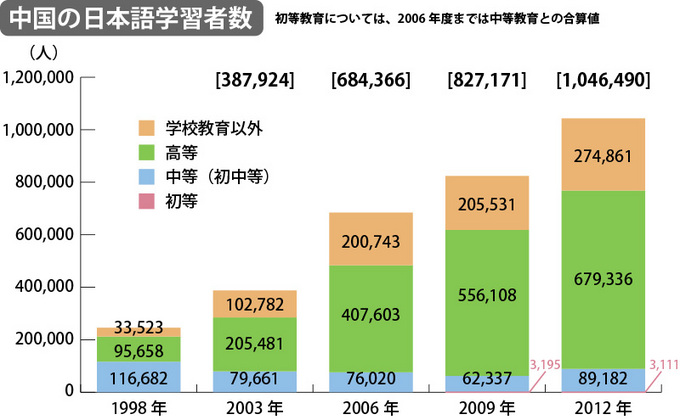

According to the "Survey on Japanese-Language Education Abroad 2012" conducted by the Japan Foundation in 2012, the number of Japanese-language learners in China has exceeded one million, and this result has made China the top country in the world in terms of Japanese-language learning.

However, future developments in Japan-China relations could have a serious impact on Japanese-language education in China. Takeji Yoshikawa, director of the Japan Foundation, Beijing, who works on the front lines of Japanese-language education in China, explains the current situation based on the latest survey results, taking a close look at factors such as education levels and regional differences.

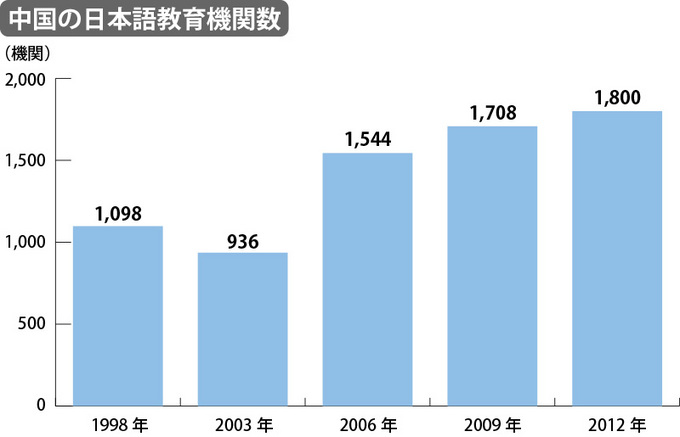

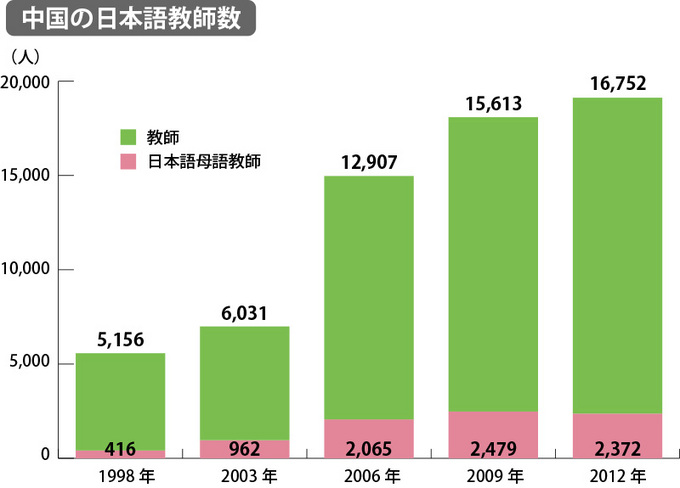

The Japan Foundation conducts the "Survey on Japanese-Language Education Abroad" every three years to gain an understanding of the up-to-minute status of Japanese-language education around the world. The 2012 survey results indicated that the numbers of Japanese-language institutions, teachers, and learners in China had all grown in comparison to the 2009 survey.

Number of Japanese-language learners in China. Figures for primary education were calculated together with secondary education until 2006.

Orange: Non-academic education

Green: Higher education

Blue: Secondary education (primary and secondary)

Red: Primary education

Number of Japanese-language learners in China. Figures for primary education were calculated together with secondary education until 2006.

Orange: Non-academic education

Green: Higher education

Blue: Secondary education (primary and secondary)

Red: Primary education

Number of Japanese-language institutions in China

Number of Japanese-language institutions in China

Number of Japanese-language teachers in China

Green: Teachers

Red: Native Japanese-language teachers

Number of Japanese-language teachers in China

Green: Teachers

Red: Native Japanese-language teachers

Specifically, compared to the 2009 survey, the number of Japanese-language institutions increased 5.4% to 1,800, and the number of teachers climbed 7.3% to 16,752. Particularly noteworthy was that the number of Japanese-language learners grew by 26.5%, or 219,319 people, and reached a total of 1,046,490. Thus, the number of learners in China surpassed the one million mark for the first time and therefore put the country into first place worldwide.

Behind these results is a long record of Japanese-language education in China.

Learning Japanese language through origami experience

Status as second most studied foreign language after English

Following the normalization of diplomatic relations between Japan and China in 1972, the relationship between the two countries became closer, and Japanese-language education in China developed steadily, keeping pace with the growth in economic ties resulting from the expansion of Japanese companies into China and other factors. By the mid-1990s, Japanese had achieved the status of being the second most studied foreign language, behind English. Japanese-language education at the higher education level (equivalent to university and graduate school) has played a key role as a driver in this field both in terms of quality and of quantity, and steady progress has been made with a range of efforts such as putting in place the education system by the Chinese side, nurturing of teachers by both Japan and China, and implementing programs where Chinese teachers come to Japan for training.

As seen in the chart above, the current survey revealed an increase in the number of Japanese-language learners in China mainly at the higher education level, and across all levels including secondary education and non-academic education. When we examine the reasons and purposes for the study in comparison to those found in other countries, the following two points can be said to stand out as the factors of the results.

China's key Japanese-language institutions gather for a conference of the "Sakura Network" (February 2013)

Objectives of Chinese people who study Japanese language

First, the reasons cited by many of those who sign up for Japanese classes in China come from their practical or utility-based objectives such as future employment at a Japanese company, studying in Japan, taking an examination, communicating in Japanese. Or some of them need it in their current job. While Japanese pop culture such as anime, manga, and fashion is a big draw, just as it is for learners in other foreign countries, learners in China also cited other reasons including interest not only in the Japanese language itself, but in learning about history and literature, politics, economics, and society, and science and technology. Thus, the interests of Chinese learners with regard to Japan are both wide-ranging and specific, and so it can be said that these learners are seeking a deeper understanding of our country.

Although the current state of Japan-China relations can hardly be described as smooth, the survey results prove that interest of the Chinese people (particularly the younger generation) in Japan and in its culture and society remains profound, broad, and undiminished against the backdrop of the strong economic ties between the two countries. The rapid spread of the Internet in China has also had a big impact by allowing instant access to firsthand information and thus to the diverse appeal of contemporary Japanese culture.

Meanwhile, the results also suggest that there are deepening grounds for concern that the number of learners will decrease unless proactive steps are taken henceforth. I would like to touch on this point later on.

Now, let's move on to take a closer look at the characteristics of Japanese-language learners in China at each education level.

Secondary teachers of Japanese language come from all over China for a training course (Summer 2013).

University students majoring in Japanese language

The results of the 2012 survey show that the greatest rate of increase is accounted for by learners at the higher education level, mainly at universities, who grew by roughly 120,000, representing 56% of the total increase of approximately 220,000 compared to 2009. In China, 506 of the country's 1,117 four-year universities have established major programs in Japanese-language, and a large number of students continue to major in the subject, with a view to getting a job at a Japanese company or doing work related to Japan in the future.

If we pick some examples of the changes in the number of learners at the higher education level, we find that the situation differs by area in the following ways: 1) remarkable growth in Beijing City and surrounding coastal cities (Tianjin City, Shandong Province, and Shanxi Province); 2) an increase in the southwest region including Guizhou Province, Yunnan Province, Sichuan Province, and Chongqing City; 3) decline in the central region including Jiangxi Province, Hubei Province, and Hunan Province (although these decreases were small compared to the growth in Beijing and the southwest region); 4) except for Liaoning Province the situation remained largely stable or numbers increased in the northeast region, which has a long history of Japanese-language education; 5) the East China coastal area including Shanghai City, Jiangsu Province, and Zhejiang Province tended toward both slight increases or slight decreases.

Chinese high school students studying Japanese--learning the language through project work

Potential for Japanese as a second foreign language at secondary schools

The number of learners at the secondary education level has increased by approximately 27,000 (43%) compared to 2009. One of the reasons for these impressive figures is that Japanese-language is becoming more and more widely taught as a second foreign language at the secondary education level.

Looking at some of these changes in Japanese-language education at the secondary education level in different regions, the situation is as follows: 1) the greatest increase in real numbers was in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, which was up by 10,000; 2) a tendency toward growth in Shanghai City and Jiangsu Province; 3) a slight decrease in Liaoning Province, which boasts the largest number of secondary education learners in all of China, and declines in both Jilin Province and Heilongjiang Province.

In the northeast region of China, there are many secondary education institutions teaching Japanese as a first foreign language. However, amid the rising trend toward English-language learning across the world, recently a growing number of schools and classes have been making English their first foreign language instead. And it results in a downward trend in the number of schools and classes teaching Japanese as the main foreign language even in this area.

In September 2001, the Ministry of Education of China ("MOE") introduced a new policy shifting the curriculum away from "exam-oriented education" purely for the sake of getting into university, and toward "quality education," which aims to nurture the whole person by fostering the human qualities of students. Foreign language education came to be positioned as something that would provide all-round support for quality education.

In this context, the number of schools offering classes in Japanese as a second foreign language is gradually moving upward, and we can see more widespread introduction of Japanese at the secondary education level in places such as Hubei Province and Guangdong Province, as well as in the northeast. If this trend of "Japanese as a second foreign language" continues to prevail across China, it is highly expected that the overall number of Japanese-language learners will also increase. However, there remain numerous problems in the actual classrooms including competition with other foreign languages, a lack of teaching materials suited to a second foreign language, and inadequacies in the system.

Japanese-language teachers working at universities across China come together for a training course

An over 30 % increase in the number of learners at private Japanese-language schools

In the segment of the survey categorized as "non-academic education," namely private Japanese-language schools and others, a jump of approximately 70,000 people (33.7%) was seen compared to 2009. It can be thought that this increase came from the learners' need for their current job or their efforts to improve their own skills, and also an extension of their interest in Japanese culture.

In addition, the spread of the Internet played a part in this upsurge, reducing obstacles to acquiring information, and thus encouraging to learning Japanese.

As a result, the number of private Japanese-language schools rose from the previous survey. However, it is difficult to get a grip on the actual situation in this segment of learners outside the academic school system, because the number of Japanese-language classrooms or schools is constantly in flux, depending on the number of prospective students, availability of teachers, management conditions at schools, and so on. This segment is also the most prone to be influenced from the status of Japan-China politics and the economy.

There are significant regional differences in the changes in the number of learners in "non-academic education." If we look at a few characteristic examples, we can see that the trends differ considerably: 1) a major decline of 43,000 learners in Shanghai City; 2) large upswings in the cities of Beijing and Tianjin, of 21,000 and 14,000 respectively; 3) steady growth in Sichuan Province and Chongqing City.

Japanese-language teachers from universities across China training together

The Japan Foundation Initiatives

Since its establishment in 1972, the Japan Foundation has continued to implement training programs in Japan and abroad for overseas teachers of the Japanese language, particularly for those who are not native Japanese speakers. In China, the "Training Center for Japanese Language Teachers," commonly called the "Ohira School," was established in 1980 as a joint undertaking of the MOE and the Japan Foundation, which was later reorganized as Beijing Center for Japanese Studies. The Center has been consistently engaged in holding teacher training programs,and also graduated programs for prospective Japanese language teachers.

The Japan Foundation has been conducting teacher training in a wide variety of ways depending on the purpose or level of learning in China. One example of the Foundation's programs is a course held in Beijing that brings together teachers from all over China. And vice versa, the Japanese-language specialists travel to cities across the county to conduct the training seminars and workshops. We also offer training programs in Japan with the purpose of offering an opportunity to take training classes, and experience Japanese society and culture at first hand.

The Japan Foundation, Beijing considers these training programs for teachers to be the centerpiece for support of Japanese-language education, and in addition engages in networking through cooperation on the development and writing of teaching materials and grants for schools and related institutions. It also conducts the Japanese-Language Proficiency Test twice each year in July and December in 41 cities across China, with over 100,000 people taking the test each time in 2013.

Furthermore, we offer Japanese-language classes for students and ordinary citizens, invite high school students for long-term stays in Japan, and pursue other projects in support of learners, with the aim of broadening the range of Japanese-language learners.

Opportunities are created year-round to allow teachers to share their various practices

(Left) A meeting of a local teachers' network

(Right) A workshop of the China Japanese Education Association

A situation that does not permit optimism

Although the number of learners is increasing and Japanese-language education in China appears to be on track, when it comes to the outlook for the future, the situation does not allow for optimism.

One factor is the direction of Japan-China relations triggered by the nationalization of the Senkaku Islands in September 2012. Japan-China tensions with regard to this issue affected multiple fronts, including economic relations, cultural exchange, studying abroad, and tourism. Because the current survey began around August 2012, after many students had completed registration for the 2012 term (September 2012 to August 2013), it was not greatly affected by the anti-Japanese sentiment that arose throughout China after September 2012.

The teachers working on the frontlines of Japanese-language education in China often find that some of Chinese students, despite of their interest, hesitate to take a Japanese course or study abroad in Japan, because their families might be concerned about that. In particular, I think that the drastic drop in learners at private Japanese-language schools in Shanghai City that became clear in this survey must be taken seriously as a foretaste of this trend.

In addition, we must not overlook the growing orientation toward English as an international language. The mainstream of foreign language education is now focused on English, and governments and schools provide excellent support systems for English education. Unless there is a change in the external environment such as a dramatic improvement in Japan's economic situation, there is not much hope of a sharp expansion in Japanese-language education as a first foreign language in institutions of higher learning where the number of programs offering a major in Japanese is already at saturation point.

A workshop for teachers on the Chinese version of Erin's Challenge! I can speak Japanese.

The key to the spread of Japanese language in the future

For that reason, I believe that the key to the future spread of Japanese-language education in China rests in how to widely promote Japanese-language education while positioning it as a second foreign language studied in secondary education in particular. According to a survey conducted by the Japan Foundation, Beijing in March 2013, there were 79 schools throughout China holding classes in Japanese as a second foreign language at the secondary education level, and the number of learners stood at 15,614. We at the Japan Foundation, Beijing are engaged in ongoing deliberations about what kinds of projects we should pursue in order to make the Japanese language more accessible and more appealing at these schools, many of which offer other second foreign language options including French, German, and Spanish.

As one of those efforts, the Chinese version of Erin's Challenge! I can speak Japanese. was published in April 2013 by the People's Education Press, a press under the leadership of the MOE. This friendly and easily understood Japanese-language learning material for Chinese learners is intended to respond to the shortage of teaching materials often cited as an issue in institutions which offer Japanese-language classes as a second foreign language.

Erin's Challenge! I can speak Japanese. was issued in Japan as a three-volume set for general use worldwide. The Chinese version, which is being condensed into a single volume, includes the additional sections of practice and activities that can be used by learners in Chinese classrooms. The text was designed to attract the interest of Chinese learners through creative devices such as using Chinese city names for the cities that appear in the text, and adding a newly-drawn cartoon in which Erin takes a trip to China. (Given that there are so many learners in China, in a sense it is only natural to produce teaching material to suit them.)

After the publication of the Chinese version of Erin's Challenge! I can speak Japanese., workshops were held first in Beijing, followed by Shanghai and Shenzhen city to give Japanese-language teachers a chance to actually see the material for themselves. In addition, we are moving ahead with the development of supplemental teaching materials, such as a PowerPoint material of the Japanese syllabary to assist Chinese learners in memorizing hiragana and katakana. We have also been preparing a web page to introduce the Chinese version. Other plans include the holding of an idea contest for Japanese-language teaching with the Chinese version of Erin's Challenge! I can speak Japanese., and the offering of seminars aimed at junior and senior high school principals to reflect on the meaning of introducing a second foreign language.

We will continue to carry out a range of projects while working together in cooperation with teachers and other stakeholders from Japan and China. By giving a further boost to the spread of the Japanese language in China, we hope to support exchange, from the perspective of Japanese-language education and learning, between the young people of both countries who will play a key role in the future of Japan and China.

Keywords

- Anime/Manga

- Fashion

- Pop Culture

- Science Technology

- Politics

- Economics/Industry

- Education/Children

- History

- Japanese Studies

- Japanese-Language Education

- China

- Japan

- The Japan Foundation Beijing

- Japan-China Diplomatic Relations Normalization

- internet

- Training Center for Japanese Language Teachers

- Ohira School

- Erin's Challenge! I can speak Japanese

Back Issues

- 2022.11. 1 Inner Diversity<3> <…

- 2022.9. 5 Report on the India-…

- 2022.6.24 The 48th Japan Found…

- 2022.6. 7 Beyond Disasters - …

- 2021.3.10 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2020.7.17 A Millennium of Japa…

- 2020.3.23 A Historian Interpre…

- 2019.11.19 Dialogue Driven by S…

- 2019.10. 2 The mediators who bu…

- 2019.6.28 A Look Back at J…