006 偶発的に仰せつかったキュレーターとしての楽しみ

プラープダー・ユン

小説家・アーティスト

私が初めてアートのエキシビジョンを「キュレーション」したのは、マンハッタンのパーソンズ・スクール・オブ・デザインに在籍していたときのことだった。当時、キュレーターが何であるのかも知らなかった。僕とルームメイトは授業に退屈し、友人たちの作品を見せるグループ展をオーガナイズしたら楽しいだろうなと考えた。パーソンズの5番街にある校舎には、学生が無料で使えるギャラリーがあった。だったらやらない手はない、と考えたわけだ。

厳密に言えば、当時の私はアート学生でなかった。コミュニケーション・デザインを専攻して1年目で、雑誌のアート・ディレクターか、または同様のファッショナブルでスタイリッシュな仕事に就きたいと考えていた。ティーンエージャー時代には、わりと長い期間、雑誌中毒だった時期があって、最先端のそして一番かっこいいトレンドを象徴していたと思われるつやつやした雑誌の類に、学業のために与えられた小遣いを遣いすぎていた。その世界に属したいと考えていたのだ。5番街を出て「ビレッジ」の方向に足を伸ばすまでは。

コミュニケーション・デザイン学からファイン・アートへ専攻という、ひとつの大きな変化を経験してからも、自分はアーティストというよりも、アートディレクターであるような気持ちでいた。クリエイティブな人々が持つ、特質すべき資質を見抜くのに長けていると思っていたし、彼らにディレクションを与えて、ふさわしい発表の場に導くことができるだろうと思っていた。私は極端に怠慢だったし(今でもそうだが)、頭のなかでたくさんのアーティスティックなアイディアが回転し続けていた一方で、自分がそのアイディアを実現するよりも、他者が実現してくれるのを見るほうがいいと感じていた。自分はなんらかのオーガナイザーとしてうまくやれると思っていた。「キュレーター」という職業が、まさにアートの世界でそれをやる人のことを指すことを知ったのは、もっと後のことだった。

しかし結局は文筆家になり、アートの世界で起きていたことは、すぐに私の人生から見えなくなっていった。必要性とは別の次元で、アートは定期的に作っていたが、誰が一番ヒップなアーティストで、次に何が来るかといった、現代アートの世界で起きていることを追うことはやめてしまった。アーティストにも、キュレーターにもならなかったわけだ。

そうはいっても、私がアートという趣味を持っていることを知る人たちのおかげで、これまで何度かエキシビジョンのキュレーターを務める機会に恵まれた。生まれながらの非社会的な性質と、現代アートについて知らないことが増えているにもかかわらず、グループ展のために、多様なアーティストたちとコラボレーションすることを享受してきた。グループ展というものは、たいていの場合、様々なメディアを使って創作するアーティスとたちが、お互いのクリエイティブな活力を確認し合う行為なので、キュレーターという経験は感動的かつインスピレーションを与えてくれるものだった。1枚のキャンバスの上で、またひとつのフレームのなかで、クリエイティブな花火が弾ける様子を、見晴らしの良い場所から見ることができるキュレーターは、恵まれているのである。

2011年の3月24日から5月15日まで、バンコクにある「100トンソン・ギャラリー」という小さいけれど有名で、国際的にも認知度の高いギャラリーでキュレーターを務めた(アーティストとしても参加した)。タイ、日本、ベルギーと、国籍もばらばらの8人のアーティストによる作品を集めたグループ展だった。不思議な縁で、8人のアーティストのなかで私が一番よく知っていたのは、名和晃平氏とミヤケマイ氏だった。メイTノイジンダ(May-T Noijinda)という有名ミュージシャンを除けば、他のタイ人アーティストは初対面の人物ばかりだった。

With the artists. From left, May-T Noyjinda, Krit Ngamsom, Zakareeya Amataya, Pasut Kranrattanasuit, myself, Nawa Kohei, and Miyake Mai (Peggy Wauters, the Belgian artist, could not attend)

エキシビジョンのタイトルは、「スピリチュアリティ」と「エンターテイメント」をかけ合わせてできた「スピリチュテイメント」という造語だった。趣旨は、アーティストたちに、スピリチュアリティ(と、または宗教)とエンターテイメントの関係について考えてもらうというものだった。多くの文化において、このふたつは正反対のものと捉えられているが、私はそうではないと考えていた。しかし、このエキシビジョンのコンセプトの基礎に、このアイディアを使おうと思ったのは、私個人の信条によるものではなかった。他の人がこの問題についてどう思うのか、またはこの問題について考えることすらあるのかどうかを知りたかった。キュレーターとしてのステートメントにはこう書いた。

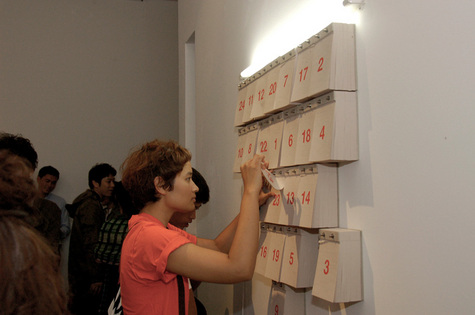

The general atmosphere at the opening night of Spiritutainment, 100 Tonson Gallery

「私のスピリチュアリティと宗教についての興味は、哲学に対する興味に由来する。歴史的に、哲学とスピリチュアリティはしばしばオーバーラップしてきた。どちらが先に人類を惹きつけたのかを確信をもって決めることはおそらく不可能だろう。古代の哲学はほとんどすべて、なんらかのスピリチャルな部分を内包していたし、その逆のことも言える。しかし、このふたつを決定的に分ける違いが少なくともひとつある。それはスピリチュアリティと宗教、特に宗教は、超自然的な、または『神聖な』存在に対する信仰を示唆するものであり、哲学は完全に実利主義的な存在でありうるという点だ。哲学はエンターテイメントと完全に合致することは可能だが、宗教の多くは公式にはエンターテイメントを禁じたり、少なくとも人間の職業として下等なものだと見なしている。私の関心の対象は、エンターテイメントとスピリチュアリティ、または宗教との間に存在する、ぎこちなく、興味深い関係だ。哲学的にも精神学的にも、様々なバックグラウンドを持つアーティストたちが作る、アートの異なるメディアを通じて、この問題についての対話を始めたかった。このエキシビションは、宗教やスピリチュアリティに対し、悲観的または楽観的な態度を表明するためのものではない。単に、観客の心のなかでもクリエイティブな対話を誘発したいとの希望から、この問題について、アーティストたちからの反応、省察、解釈を得たかった。アートはミステリアスな方法でも作用するものなのだ」

My own work, The Number God, is based on a popular fortunetelling technique

この展示は私にとって、新しいタイの現代アートのアーティストたちと出会い、日本人のアーティストの友人たちの作品をタイに紹介する機会にもなった。名和晃平氏は、タイの熱心なアートファンたちの間で一種のセレブリティである。彼の人気の作品である球体に覆われたシカの彫刻は、一時、バンコク・アート・センターに展示され、多くの観客を呼ぶ力があることを証明した。一方、ミヤケマイ氏の作品はタイの市民にまったく馴染みのないものだったが、「God Has Many Names(神には多くの名前がある)」と名付けられたインスタレーションは、日本の伝統的なクラフトマンシップと現代のコンセプチュアルなアート感覚を繊細に融合し、観客を感心させることに成功した。エキシビションは、3月11日の津波の悲劇からそう時間が経っていない時期に開催され、現場に日本の芸術作品やアーティストたちがいたことは、エキシビションが企画されたときにはまったく意図しなかった感情を引き起こした。

Nawa Kohei's Pix-celled Buddha getting a close inspection

Miyake Mai explaining her work

このときのように、コンセプトが抽象的なエキシビションを企画するとき、「メッセージ」が観客にどれだけの影響を及ぼすのか、またコミュニケーションがまったくあったのかどうかを見極めるのはいつも難しいものだ。しかし、オープニングの夜、アーティストたちがお互いと、そして観客たちと様々な方法で交流する様子を、私は心から堪能した。ほとんどお互いを知らないアーティストたちが意気投合し、互いを共有しあう姿を見るのは満足できる経験だった。

クリエイティブな精神というものは、瞬時に人を感動させることもあるし、誰かの人生にじわじわと染みこみ、浸透することもある。それはキュレーターがコントロールできる範囲の外のことだ。それにしても、原材料を選び出し、アートという名のボウルに入れて、味わい深い、ヘルシーな食事ができる、ということは幻想ではない。

006 The Joyous Case of an Accidental Curator

The first time I ever "curated" an art exhibition was when I was studying at Parsons School of Design in Manhattan. I didn't even know what a curator was at the time; my roommate and I were bored of our classes and we thought it would be fun to organize a group show of our friends' works. There was a small gallery in Parsons' Fifth Avenue building that was available for students to use free of charge, so we thought, Why not?

Strictly speaking, I was not an "art" student at the time. I was in my first year as a Communication Design major, thinking that I wanted to become a magazine art director, or something fashionable and stylish like that. As a teenager I went through a rather long phase of being a magazine addict, spending too much school allowance on all kinds of glossy periodicals I thought represented the latest and coolest social trends. I thought I wanted to belong in that world, until I stepped out of Fifth Avenue and ventured downward towards "the Village."

Even after making the big switch from Communication Design to Fine Arts, I still thought I was art director, rather than artist, at heart. I thought I was good at recognizing remarkable qualities in other creative people and could probably direct them and their works to appropriate venues. I was (and still am) extremely lazy, and even though I had a wheel of artistic ideas spinning in my head constantly, I'd much prefer to see other people execute those ideas than to carry them out myself. I thought I'd be a good organizer of some kind. I only found out later that a "curator" was someone who did exactly that in the art world.

But, as it turned out, I became a writer, and most of the art world activities soon receded from my life. I still made art regularly, more for pleasure than anything else, but I no longer kept up with what was happening in contemporary art, who was the hippest artist, what was the next big thing. I became neither an artist nor a curator.

However, probably because some people know of my hobby, I've been lucky enough to have been asked to curate several exhibitions. Despite my innate antisocial tendency and my growing ignorance of contemporary art, I've enjoyed collaborating with diverse artists on group exhibitions. I've generally found the experience to be touching and inspiring, as it's the kind of activity that reaffirms mutual creative drives among artists of all mediums. And the curator is lucky to be at the vantage point, to be able to observe these creative fireworks bursting together on the same canvas, in the same frame.

From March 24th to May 15th of 2011, I acted as curator (and participated as artist) for a small but well-known and internationally recognized gallery in Bangkok called 100 Tonson Gallery. It was a group exhibition of works by eight artists of various nationalities, namely Thai, Japanese, and Belgian. Strangely enough, of all the artists in the group I'm most familiar with the Japanese Nawa Kohei and Miyake Mai. All the Thai artists--except May-T Noijinda who is a famous musician--I knew and met for the first time.

The exhibition was called "Spiritutainment," which is a word mutated from the marriage of "spirituality" and "entertainment." The idea was to ask the participated artists to think about the relationship between spirituality (and/or religion) and entertainment. In many cultures the two are considered opposites, but I believe the contrary. However, it was not what I believed that inspired me to use the idea as the conceptual basis for the exhibition. I was interested in what other people thought about it, whether they thought about it at all. Here's what I wrote for the curator's statement:

My interest in spirituality and religion stems from my interest in philosophy. Historically, philosophy and spirituality often overlapped; it's perhaps even impossible to know for certain which appealed to human beings first. Almost all the ancient philosophies of the world contained some spiritual aspects, and vice versa. However, there is at least one crucial difference that separates the two: spirituality and religion--especially religion--imply some kind of faith in the supernatural, or the "divine," while philosophy can be totally materialistic. Philosophy can be in complete agreement with entertainment while many religions officially forbid it, or at least regard it as an inferior human preoccupation. I am interested in this awkward and curious relationship between entertainment and religion/spirituality. I wanted to get a dialogue going on the issue, through different artistic mediums, by artists from diverse backgrounds, both philosophically and spiritually. The exhibit is meant to be neither pessimistic nor optimistic toward religion/spirituality. I simply wanted to get "artistic" reactions, reflections, and interpretations from the artists in regards to the subject matter, with the hope to provoke a creative dialogue within the mind of the spectator. Art also works in mysterious ways.

The exhibition was a good opportunity for me to meet and work with new contemporary Thai artists as well as to have the chance of introducing the works of my Japanese artist friends to Thailand. Nawa Kohei, is already a kind of celebrity among young Thai art enthusiasts. One of his popular Pix-celled Deer sculptures was displayed at the Bangkok Art Center for a time and it proved to attract many visitors. But Miyake Mai's work was totally new to the Thai public, and I think her God Has Many Names installation managed to impress the spectators with its delicate mixture of Japanese traditional craftsmanship and contemporary conceptual art sensibility. The exhibition happened not long after the March 11th Tsunami tragedy, so the presence of Japanese artworks and artists at the exhibition had a feeling that was completely unintended when the idea for the exhibition was formed.

It's always difficult to tell, with an exhibition with concept as abstract such as this, how "the message" effected the spectators, or whether communication occurred at all, but I thoroughly enjoyed the various ways the artists interacted with each other and with the visitors on the opening night. It was especially satisfying to see the artists who hardly knew each other getting along and sharing so well.

The creative spirit can strike instantly or it can seep in and work its way into a person's life slowly. That's beyond the curator's control. Nonetheless, the joy of being able to pick out ingredients, throw them into a bowl of art, and end up with a tasty, healthy dish is not an illusion.

プラープダー・ユン

プラープダー・ユン

1973年生まれ、バンコクに拠点を置くタイの小説家・アーティスト。

多数の小説、短編小説やエッセイのコレクションを出版し、「ライ麦畑でつかまえて」「時計じかけのオレンジ」のような現代英語の古典文学もタイ語に翻訳。2002年に、彼の短編小説のコレクション「存在のあり得た可能性(英題:Probability)」で、タイで最も権威ある東南アジア文学賞を受賞。 他、プラープダーは定期的に日本で雑誌に執筆したり、アートのエキシビションを開催。また、映画「地球で最後のふたり」「インビジブル・ウェーブ」(主演:浅野忠信)の脚本や、現代アーティスト名和晃平の様々なアートプロジェクトにも協力。最新の小説は「パンダ」

Prabda Yoon

Born in 1973, a Thai writer and publisher based in Bangkok. He has published numerous novels, short story collections, and essay collections. In addition, he has also translated modern English-language classic literature such as The Catcher in the Rye and A Clockwork Orange into Thai. In 2002, his short story collection, Kwam Na Ja Pen (English: Probability), won the SEA Write Award.

Apart from working in Thailand, Prabda has regularly written for Japanese magazines and exhibited artworks in Japan. He has written 2 screenplays for films starring Tadanobu Asano and he is presently collaborating on various art projects with Japanese contemporary artist Kohei Nawa. His literary works have been translated into Japanese, of which the most recent is the novel Panda.