Japonismes 2018 (Vol. 2)

MANGA⇔TOKYO

MANGA⇔TOKYOJapanese manga, anime, games, and tokusatsu, and Japonismes 2018

Kaichiro Morikawa

Associate Professor, School of Global Japanese Studies, Meiji University

I served as curator for MANGA⇔TOKYO, an exhibition featuring manga (comics) and anime (animation) that was held in Paris as part of Japonismes 2018. The Japanese government's desire to present manga and anime abroad reflects the popularity that these cultural products have been enjoying in other countries. This includes France, where you can often find anime screened on TV and at cinemas, as well as manga lining the shelves of bookstores. They are compared and consumed as commercial products, and loved as pure entertainment. It is in that instance that they shine so brilliantly, and that is why an exhibition cannot do justice to them by just sticking some samples of illustrious "works" in frames and hanging them on a gallery wall. So, the question for us was: How could we meaningfully present those modes of expression?

We decided to make not an exhibition of manga and anime, but an exhibition through manga and anime. What, then, were we going to present through them? With an expansive 3,500 square meters of exhibition space at our disposal, we decided to showcase the metropolis of Tokyo. Why Tokyo?

As exemplified by Dragon Ball, completely fictional universes provide the setting for various Japanese manga, anime, games, and tokusatsu (a genre of films and TV shows characterized by their use of certain special effects techniques). However, there are countless other works that take place in real-life locations, particularly Tokyo. In fact, there are so many set there that together they form a contemporary version of One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, the renowned 19th century series of woodblock prints depicting sights in Tokyo. And, the "hundred views" they offer span a multitude of eras and perspectives—Tokyo during the Japanese economic miracle or the economic bubble years, Tokyo today, Tokyo in the eyes of girls, youths, or homemakers, and many other Tokyos.

What's more, these media take Tokyo and its various locales to a dimension beyond being a mere pictorial backdrop for certain scenes. For example, in work after work—Godzilla, Akira, and Neon Genesis Evangelion, to name a few—Tokyo is devastated again and again by some uncontrollable and unfathomable force. When we look for the reality that lends verisimilitude to that fiction, we see the history of a Tokyo that has been repeatedly reduced to rubble by earthquakes or other catastrophes and has each time rebuilt itself, and a Tokyo that is virtually destined to meet with such calamity again in the future. The cycle of urban destruction and rebirth in tales such as Akira and Evangelion echoes the historical timeline of Tokyo.

As this illustrates, manga, anime, games, and tokusatsu have, through the lens of fantasy, mirrored the reality of Japan across diverse generations and phases. And, therein lies part of their unique cultural value. It was with this reasoning that we decided to communicate the values and qualities of those media by presenting "Tokyo" as portrayed by them.

The exhibition layout was inspired by the spatial design of Shinto shrines, which are often depicted in anime. The entry zone recreated scenes of Akihabara and Otome Road—two areas of Tokyo filled with anime-themed shops—in a manner like the bazaars in front of shrine gates during festivals. From there, a walkway similar to the path leading to a shrine guided visitors to a model of Tokyo that measured a colossal 22 x 17 meters and symbolically functioned as a kagura stage where sacred dances are performed. Projected onto a large screen behind it were images of various pop culture characters, assuming the avatars of the local spirits enshrined, in scenes set in specific parts of the metropolis.

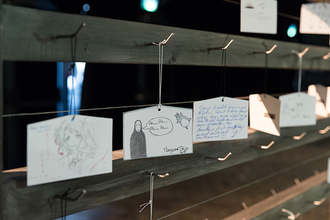

In keeping with the shrine motif, a side area of the hall featured a message board patterned after the panels at shrines that display ema, small wooden plaques on which visitors write their wishes. At the exhibition, ema-shaped cards were provided for visitors to jot down comments or draw their favorite character. To my delight, the board became covered with cards from people of all ages in just a few days. The many lengthy comments posted on it revealed to me our visitors' strong fascination with the exhibition.

A memorable moment for me was when I saw the joy that a local college student on the exhibition staff displayed upon receiving this comment from an elderly couple: "We didn't know much about Japanese comics, but we were really impressed by their cultural richness." Moments such as this and the many message board cards bearing drawings of beloved characters gave me a renewed sense of just how much Japan's manga, anime, games, and tokusatsu have attracted the French audience over the years.

I offer my deepest gratitude to everyone who contributed to MANGA⇔TOKYO.

Kaichiro Morikawa

Kaichiro Morikawa

Associate Professor at Meiji University's School of Global Japanese Studies. Received an MA in Architecture from Waseda University. While serving as commissioner of the Japanese pavilion at the Venice Biennale 9th International Architecture Exhibition in 2004, he produced the exhibition Otaku: persona = space = city (organized by the Japan Foundation). He assumed his current position in 2008. He has taken part in the establishment of the Yoshihiro Yonezawa Memorial Library of Manga and Subcultures, and is presently committed to the preparation for the planned Tokyo International Manga Library (tentative name). His publications include Learning from Akihabara: the Birth of a Personapolis (Gentosha, 2003).

Keywords

Back Issues

- 2022.7.27 Beyond Disasters - T…

- 2022.6.20 Beyond Disasters - T…

- 2021.6. 7 Contributed Article …

- 2021.4.28 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2021.4.27 Contributed Article …

- 2021.4.20 Contributed Article …

- 2021.3.29 Contributed Article …

- 2020.12.22 Interview with the R…

- 2020.12.21 Interview with the R…

- 2020.11.13 Interview with the R…